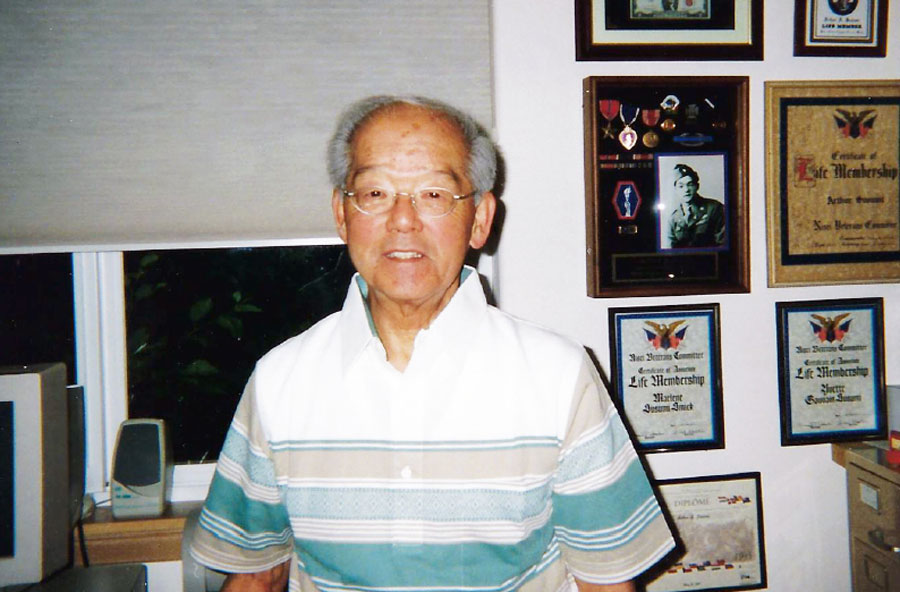

Quiet Warriors Art Susumi

By Mikiko Hatch-Amagai, for The North American Post

“No, I wasn’t afraid. I saw a lot of dead bodies around me during the war,” said Art Susumi, who became an undertaker at the age of 22.

That was his answer to the question, “Are you afraid to sleep under the same roof with dead bodies?”

Art received a Bronze Star during World War II for rescuing wounded soldiers of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in spite of his own injuries. After the war was over, he became the only Japanese American funeral director in Washington State. He retired from E. R. Butterworth Funeral Homes in 1991 after 43 years of service to the Japanese community. One wonders how the war influenced young Art and his choice of profession.

Susumi was born in pre-war Nihonmachi, not far from Nippon Kan Theater at 8th and Washington, Seattle. His father came from Fukuoka, Kyushu, worked at a waffle house in Georgetown, Seattle, and later operated a small flower shop in Youngstown, West Seattle. His mother came from Nagoya, and worked as a maid in a hakujin (white man’s) home. Young Art grew up during the Depression, helping in his father’s shop. He graduated from West Seattle High School in 1941, just before being relocated to Puyallup and then to Minidoka.

At Minidoka, Art volunteered for the army in 1942 and joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team as one of the original mainland volunteers. There, he met Nikkei from Hawaii.

“It took several months to get across to them.”

He talks about how they couldn’t get along with each other early during their training at Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

“But we went to the dance together and they began to hear what we went through. They didn’t know about camps, but they understood then. We are very good friends now.”

There were visitations to the relocation camp at Rohwer, Arkansas, for a treat to meet girls during the first six weeks for the soldiers, who were “separated from the rest of civilization.”

Then, they shipped overseas in 1944. The convoy carrying the Nikkei soldiers took 28 days to cross the Atlantic. They landed in Naples, Italy. Art was assigned to Cannon Company and his job was to carry a 40-pound radio around.

“It was heavy. The radio was so big. You carry your own pack and the 40-pound radio. I sat on my helmet sometimes,” said Art, who is of rather compact build.

The 442nd RCT went through the battle of Anzio, near Pisa, then to rescue “The Lost Battalion” in eastern France.

“We just followed the orders. Officers knew about the principles of war, where they were heading to. We were too young to think. We didn’t have time to think.“

They rescued Texans of the 141st Infantry Regiment, who were surrounded by German enemies. Art was wounded by the trees falling and by shrapnel pieces when taking cover in a foxhole.

“It just missed my spine. Small pieces are still there but the medics said it was too dangerous to take them out.”

Art risked his life to relay fire missions to his rear Command Post and to aid his wounded buddies. He was awarded the Bronze Star and they all became honorary Texans.

Art thinks he was very lucky to be in the Cannon company. Other companies in the 442nd infantry lost so many men.

“Like K Company, they lost all but four people. They showed up at a parade, the Colonel asked ‘where were the others?’ and the commander said they were either dead or at the hospital.”

Art knows he’s lucky, not only because he survived, but because of the camaraderie.

“When you go through battles, you become very close, nothing matters except to survive. We were together, we got through….”

They still keep in touch and he goes to Hawaii to see his Hawaiian buddies.

“We all did the job and we are very proud of what we did,” Art added, petting his pet poodle by his side.

After the war, his family returned to the Renton Highlands area. Art’s father died of his second heart attack in three years. Young Art, though the only boy in the family, didn’t know what to do when death occurs. The director from a small funeral home, recommended by the doctor, handled everything, and the experience touched Art. He asked the director, Maurice Walker, if he was interested in advertising in the Japanese community in Seattle, to serve it when it needed help.

“He turned the tables on me and said I should come to work for him and start helping my own community. This was a quite shock, and after discussion with my family and some close friends, I decided to try.”

It is in the area of “untouchables” work in Japan.

“But nobody here in my community ever made a big deal of it with me. At least not to my face.”

Susumi moved into the funeral home. Not only did he get the job in 1946, when it was hard for Japanese Americans to get a job. He got to drive the ambulance!

“At age 22, this was an exciting thing to do; you know, siren, red lights flashing, and high speed driving… it made up for a lot of drudgery.”

After a year, Art decided to go to the Cincinnati College of Embalming, Ohio. After graduating summa cum laude, he made a connection with Jim Murphy, the manager at Butterworth, who was also a graduate from the same college. Susumi worked there for 43 years.

In directing 5,000 funerals, Susumi took care of 4,500 Japanese. Although retired now, he assists Japanese or Chinese families on request.

In the beginning, it was easier since the funerals were for his parents’ generation.

But “now, they’re for friends and it gets harder and harder,” Art says.

The Nikkei funeral has many different ways: each church, Buddhist or Christian, has its own way of commemorating the dead. In the days when they had “Otsuya,” or wakes, at residences, they had to remove doors from hinges or slide caskets from windows.

Art’s respecting the dead and accommodating the surviving families served the needs of the Nikkei community. And that may be the reason why he is popular.

“Because I had witnessed war, it didn’t bother me to see and work with dead human bodies; however, dealing with death here and now is different because, as a funeral director, I am also dealing with the survivors.”

Susumi takes care of people and his reputation extends outside the Nikkei community. He became the first Nikkei Commander of Disabled American Veterans this year.

“Kids now are fortunate,” Art answered to the question, “Any words for the next generation?”

“The groundwork (to be accepted as Japanese American) is done, the field is wider and they have support from their parents,” says Art who grew up in a merchant family.

“There is no limit to the professions. I am proud of the Sansei.”

His compassion towards his comrades lost in the battlefield, whom they couldn’t bury, or just towards people in general, exudes through his face, beaming with smiles.

Editor’s note. This article, the fifth in the 13-article series, is reprinted from The North American Post-Northwest Nikkei, July 26, 2003. The remaining interviews will appear monthly across 2021.