By David Yamaguchi, The North American Post

Photos by Wendy Sheridan

In late April, the NAP received an email query out of the blue from Chizuko (Chiko) Tsukamoto-Jaggard, Executive Director of “Project Returned Memories” [Kiseki], in Carlock, Illinois. A woman in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, would soon be sending a World War II Japanese soldier’s diary back to his surviving family in Japan. Would the NAP be interested in covering the story?

After conferring briefly, the staff agreed it was of interest. These days, baby boomers are busy cleaning up their parents’ homes. Moreover, in the Seattle Japanese-American community, some Nisei fathers had been Military Intelligence Service (MIS) linguists serving in the Pacific. Who knows what might turn up? Would local Sansei know what to do with similar found items, beyond perhaps turning to the Japanese Cultural Center of Washington (jcccw.org) or Japanese Consulate?

The Milwaukee lady is Wendy Sheridan, an artist. Her story is that her father, James M. Wink, a Lieutenant in the Army Medical Corps, had been a medic on Iwo Jima, an experience he scarcely spoke of, probably because he was traumatized by it. Recall that Iwo was the tiny island that lay along the US bomber route to the Japanese mainland from the Mariana Islands. From its airfield, Japanese planes rose to harass the bombers. The US wanted the eight square-mile island as a refuge where damaged bombers could land on the return trip and as a base from which it could launch its own fighter planes to protect the bombers. After Iwo, only Okinawa lay in the path of the American invasion of the Japanese mainland.

As Ms. Sheridan relates in a December 2015 interview for the “Wednesday Journal of Oak Park and River Forest” (oakpark.com), her father told her only that his job had involved vaccinating American soldiers and supervising African American sanitation corps soldiers in burying the dead.

The Japanese soldier’s diary was among her father’s belongings she found in the garage. If possible, she wanted to return it to the soldier’s surviving family in Japan. But was it possible to find them after the passage of 70 years?

Ms. Sheridan eventually found her way to Ms. Jaggard, whose organization’s mission byline is “Let War Memorabilia Come Home.”

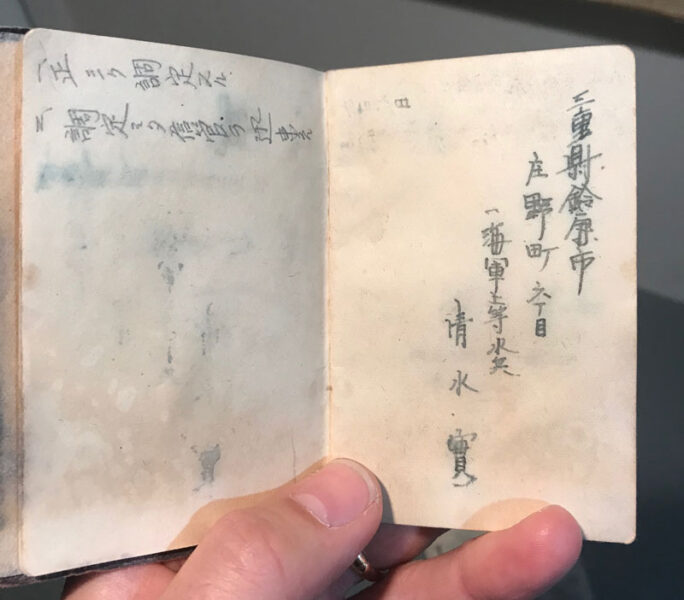

In the Sheridan case, the Japanese soldier, “Hiroshi” Shimizu, was a lieutenant in charge of an anti-aircraft gun crew, according to Yoko Avramov, the first translator Ms. Sheridan found. In addition to recording plane flyovers, bombings, and troop landings, he had had the foresight to write his name (actually Minoru), village, and city neatly in ink (photo), giving Ms. Jaggard a reasonable chance of finding his present-day family. The key points are Mie Prefecture—the northern Kii Peninsula countryside west of Nagoya—Suzuka City, and Shono Village, Sixth (city) block.

Today, on Google Maps, Suzuka is a city of 200,000 that splays widely across the southeast bank of the northeast-flowing Suzuka River. West of the city center, the river is crossed by a Shono Bridge, which on zooming in, leads to the former village of Shono. By chance, Shono is one of the 53 historical stations—overnight rest stops—painted by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) on the Tokaido, the famed Edo-era road linking Kyoto and Edo (Tokyo). Zooming in further, block 6 becomes visible as one of the last three numbered blocks at the southwest edge of the village.

Finally, changing from map view to satellite view, it becomes clear that Block 6 is one of two clusters of houses that look out onto vast farm fields lying west of the village.

Before starting his military diary (Dec. 1937), Shimizu Minoru had been a country boy. Still, across decades, families move, names change, and the like. Do present-day residents of Shono remember him?

Shimizu’s last entry is on February 17, 1945, when he writes, “Today our unit will go to take the Americans.”

He thinks of his parents and hopes that “Tazuko,” perhaps a wife or sister, will care for them.

Shimizu closes with the lyrics of a song, “Umi Yukaba,” which come from a poem written by Otomo no Yakamochi (ca 718-785) in the Manyoshu poetry anthology. It was set to music in 1937 and has been sung thereafter in Japanese military circles, except when it was banned during the U.S. Occupation of Japan (1945-1952). Today it continues to be sung by Japan Self-Defense Forces.

“Umi yukaba

Mizuku kebane

Yama yukaba

Kusa musukabane

Okimi no heni koso shiname

Kaerimi wa seji.”

[At sea be my body water-soaked,

On land be it with grass overgrown,

Let me die by the side of

my sovereign

Never will I look back.]

Two days after this entry, the US Marines landed on the island and began a battle which few Japanese soldiers would survive. Anticipated by US planners to take a week, it persisted for five weeks (until March 26th), as the Japanese unexpectedly fought from well-prepared positions in caves and tunnels. The dead included 18,000 Japanese and 6,800 Americans.

The battle is remembered in many books and films, including “Letters from Iwo Jima” (with Ken Watanabe), and “Flags of Our Fathers.” The twin films were made in 2006 by Clint Eastwood, who recognized that if you have two opposing armies of actors on a remote shoot to make a movie, you might as well make two, one from each side.

Today, no Shimizus live in Shono, Block 6. Still, Ms. Jaggard was able to locate a nephew, Tazuko’s son, who watches over the family cemetery plot.

Might the NAP do a follow-up story on him?

According to Ms. Jaggard, “at this point in time, the… son doesn’t want the Japanese media to cover this story… Wendy is planning to write a note and [will] send it with the diary… If he writes back, a follow-up story may come out. I will also encourage him to respond to Wendy… it is quite often the case that Japanese families are shy or uncomfortable to be contacted by the media. Again it is often the case that they open up later.”

Project Returned Memories Kiseki

PRM found Minoru Shimizu’s family for Wendy Sheridan. According to Executive Director Chizuko Jaggard, it is the only nonprofit that handles all kinds of Japanese WWII artifacts, especially “flags, postcards, pictures, and other personal items with clues to identify original owners or their families.” Since 1971, it has returned hundreds of war memorabilia to families in Japan. In 2018, it arranged an NHK interview with a Florida woman whose father had many artifacts from Saipan, over 30 of which PRM has repatriated to Japan. It does not collect items from donors until families are found.

Website: https://kiseki-ihin.tokyo/

(Mainly in Japanese, but has some helpful English content.)

Contact: senso_ihin@outlook.jp