By Mikiko Amagai, for The North American Post

“Equality and justice, that’s the foundation,” Paul Hosoda says about his beliefs. “[We] all should be given the same chance to be treated equally as everyone else…That’s God’s gift.”.

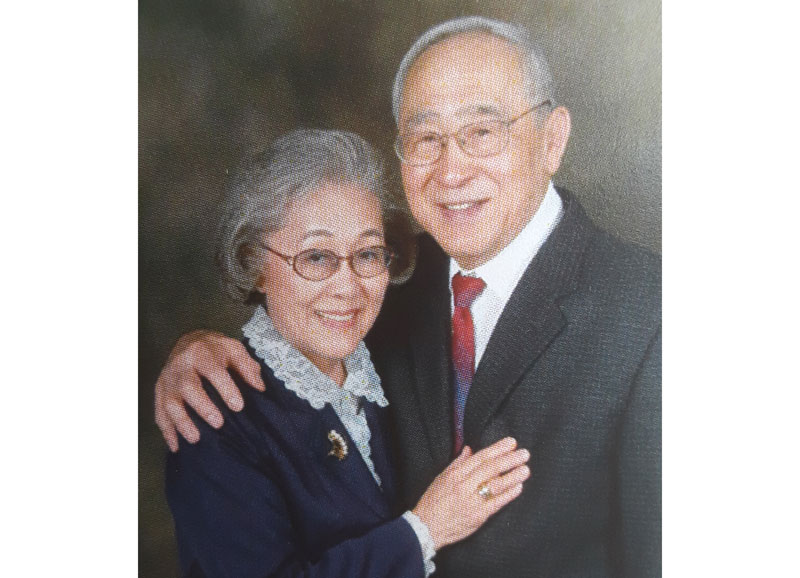

Sitting next to Paul, his wife Mary smiles. They have been together for 48 years, since they met at Blaine Memorial United Methodist Church after the war.

“We (Fort Lewis Nisei) spent weekends in Seattle and on Sundays, I went to church—of course, to meet girls. It’s a good place to meet,” he smiles. His faith in justice comes from Christianity, but was also affected strongly by his experiences in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team since he was 17 years of age.

Born and raised in southeast Idaho, Paul never went to relocation camp. His father had a restaurant but leased it out during the war. Paul was attending the University of Utah when the Japanese navy attacked Pearl Harbor. He volunteered for the army, but being an “enemy alien,” didn’t get accepted.

Later, hoping to join as a cook, Paul went to a cooking school. In 1943, the classification of Japanese Americans changed and he was finally able to enlist in the army. First, he went to Ft. Douglas, Utah, then to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, where the 442nd RCT was formed. There, he encountered unexpected problems.

The 442nd, supposedly all Japanese Americans, was obviously divided into four groups: people who came from Hawaii, mostly draftees without much previous experience in the service; Californians, dressed somewhat gaudily with urban “manners;” quieter people from the Northwest with camp experience who seemed to know each other through friends and relatives; and the others with no experience in the camps who came from (inland) all over the country.

“The draftees from the mainland had experience in the service and had leadership positions. The Hawaiians didn’t like that. They wanted their own people for the team leaders and so forth,” Paul explains.

“Then, there was the problem between mainland Nikkei and those from Hawaii. Also, there was the conflict of language: the Hawaiians spoke pidgin English. They thought we were showing off our good language.”

“The group of us (not from camps) had no specific ties or association. (We were) closer to hakujin [white people]. They (each group) had their own clique,” he remembers.

“Once you got in combat, everything was changed. They learned to accept others, their differences were resolved. We worked together, suffered together, we were all buddies. You become true brothers.”

In July 1944, Paul was assigned to F Company, 2nd Battalion as a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) man and shipped overseas. Landing in Italy in July 1944, they went north. Around “Hill 140,” Paul was “blasted out” and sent to the hospital with a head injury. Knocked out, he doesn’t remember how long he was in the hospital: “until the 442nd went to France.” Then, he was reassigned to a transportation company, a unit in Naples. He was reassigned again, but this time back in the US, to Fort Holabird, Maryland.

“Before the war was over, there were 20-30 Nisei soldiers there. There were all kinds of rumors that we were going to be dressed up like Japanese soldiers to be taken around to be shown how Japanese look, or we might be used for dog training because we were supposed to be smelling like Japanese. It never happened to me though.”

It was that kind of era: discrimination was a part of life in those days.

Paul was discharged in 1946 but stayed in the reserve unit. He thought, “if there is a war again, at least I could be assigned to something I like.”

He was one of many who stayed.

In 1950, the Korean War broke out. Paul was on active duty, sent to Korea but this time as a warrant officer. He became a Combat Engineer in 1953, then transferred to the Military Intelligence Service, where he first interrogated Korean prisoners of war, before being sent to Japan for a year. His job there was to examine the applications of war brides.

“I felt sorry for them. Sometimes, GIs tried to look bigger than what they were.”

He talks about his impressions.

Finally, he was transferred to Ft. Lewis to its Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) until he retired. The duty was to investigate people, mostly Nisei, and to give recommendations on their suitability for jobs.

Now, thinking back about Japanese Americans, Hosoda feels very proud of his Japanese ancestry. All Japanese during the wartime period, including Issei, were obedient. Sometimes, they were discouraged and disappointed, but they did not bring shame, which would reflect on all Japanese people.

Those who went out from the camps worked hard and established a reputation as good workers. In the military, even though they were first classified as enemy aliens, their reputation was that they were dependable, trusted by all. They didn’t complain about civil rights or that they should be treated as citizens.

The No-No Boys had a special situation. Their standpoint was the application of justice, with equal and fair treatment.

“All those people proved to be lawful immigrants and citizens. To me, that is very important. We should strive for all of us, regardless of who you are. Whether you are immigrants or citizens. We all should get equal and fair justice and treatment.”

“Their effort to gain equality and justice, that’s the foundation. Everyone, whether they were in camp or not, did prove themselves to be good citizens, loyal and good workers. To me, those messages should alert some of the other people, youth and other immigrants, ‘Hey, if you want the right, prove yourself and conduct yourself as good citizens, not just demand to treat me or give [me] those rights. At least, show that you deserve the right. If you don’t, people don’t believe you.’”

“Don’t expect everything to be handed to you. Prove yourself and go after it. Japanese (Nikkei) should be proud of the way they conducted themselves, without disgracing the Japanese people, without monku [complaining, they] went to camps, [with] all kinds of discrimination and treatment.”

“Among the choices available to Japanese Americans,” I asked, “why did you volunteer to be a Nisei soldier?”

“To prove for my folks’ sake that Japanese Americans are just as good as any other people, trustworthy and loyal. My dad couldn’t get citizenship, but after the war, they changed the law and my dad was one of the first ones in the Pacific Northwest to get the citizenship.”

When the war was over, they were still in Idaho. Paul and his brother helped their father in the restaurant, trying to get it back into shape again.

Through his experience of war, Paul learned to live together with others, to respect others’ beliefs and religions, even at Camp Shelby where all the Japanese Americans were so different, and to try to understand what lies behind their behavior. If one tries to impose his belief or opinion on the other, war can happen. 9/11 was an example. It was like a combat situation without regard to the people, just revenge. Everybody suffered.

“I may be a peace lover but I would object to anyone denying me peace in the way of life I want.”

You have to defend and protect it if that’s what you believe in because equality and justice are for all. That is Paul’s foundation.

“Where is your fairness coming from,” I asked.

Paul responded, “The experience of army life, to get along with your own race, [to understand] where they came from and why they act like that. They should be given the same chance to be treated equally as everybody else.”

Paul talks about the Golden Rule.

“That’s God’s gift. All religion has [role] models (Mohammed, Jesus); all of them to me [are] all disciples of God, regardless of what you call them. I think in every religion, you will find pretty much the same things (do the things that you want them to do to you), [be] good to each other, practicing acceptance. Under God, we are all equal; the Bible, the Koran say the same thing, but the difference is how to interpret [it].”

“Did your religion help you during the war?” I asked.

“There are no atheists in foxholes. You know whether you die or live is something that you can’t control.”

He answered with a light that shined in his smile.

Editor’s notes. “Hill 140” involved a battle to take a hill in the Arno River valley, near the town of Castellina Marittima, in Tuscany, Italy. The 442nd began its southern France campaign on August 15, 1944. Hawaii Nisei were actually used in army dog-training experiments in Mississippi in 1942. Several first-person accounts are on nisei.hawaii.edu. Nisei soldiers were useful for interrogating Korean soldiers, as both spoke Japanese, the latter because Korea was a Japanese colony during 1910-1945.