By Mikiko Hatch-Amagai, for The North American Post

“[A] Bronze Star doesn’t really mean very much. Every soldier that was overseas got it. This is the Silver Star and this is the Purple Heart. Dog Tag. And the Presidential Citation. And this is the discharge paper,” explains Mitsuru Takahashi showing the framed memoirs with a smile. His wife June, the high school sweetheart from Minidoka Camp, put it together.

“Where did you get hurt?” I asked him.

The expression on his face turned stiff and he answered, “I got wounded in the shoulder. The bullet grazed but missed the bone and the lungs. No surgery or anything. I was very lucky.”

Mitsuru’s father, a gardener, came from Nagano Prefecture. After World War II, he was involved in making the Japanese Garden at the Arboretum.

Mitsuru was born in Seattle. In 1942, Mitsuru, his parents, and his three sisters were evacuated to Puyallup, then to the Minidoka Camp.

Mitsuru was born in Seattle. In 1942, Mitsuru, his parents, and his three sisters were evacuated to Puyallup, then to the Minidoka Camp.

After graduation from the high school there, he volunteered to join the army. He was sent to Florida, then trained at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and was assigned as a BAR-man (Browning Automatic Rifleman) to L Company of the 442nd Infantry Battalion.

“The first impression of the war when we landed to Le Havre, France. It’s a good sized city but there was nothing on the waterfront, absolutely nothing, just rubble of concrete and bricks of the first half mile, four or five blocks. [The] Farther we went in, we saw damaged buildings.”

The 19 year-old Takahashi realized this was war. Then his troop was sent to Southern France and to near Pisa, Italy. It was right after the Lost Battalion rescue (1944).

“It was about Thanksgiving. Instead of a hot dinner, we had cold sandwich and coffee. It was very disappointing.”

They went through Florence, then into the mountains, marching all night long to a little town. Then the next night, they climbed up a hill, up to 3,500 feet.

“You know, Mt. Si? It was like Mt. Si, straight up high.”

The hill was the dividing line, where neither side could advance for five or six months.

“Our regiment climbed up the hilltop and took it over in two or three hours. [The] Germans couldn’t believe it,” exclaimed Takahashi.

The Germans surrendered and this was the reason for the President’s citation award. Next, the regiment walked the Po Valley and down the hill to Corona, where Mitsuru was hurt in the enemy’s ambush. The BAR men were reduced from 180 men to 70 or 80 men.

“I was eighteen or nineteen, too young to be scared or to be intelligent.”

If soldiers were 30 or 40 years old, they’d never be able to fight. Like any young man, without thinking what war was all about, he found himself on the edge of life and death. The bullet went in from his shoulder and through his back without hurting his bones or lungs.

The doctor said, “if you took an ice pick, you couldn’t have done a better job.”

But Mitsuru almost became unconscious and still had to walk three miles down the hill.

He heard the news of D Day in the hospital.

“We just sat there, no excitement or happiness. No emotion, but a relief. The people, like in supplies (in the rear) had celebrations, but actual soldiers were relieved, more than (feeling) happy. We just kind of sat there. We cried there, I think,” he remembers.

Sometimes, when an emotional thing happens you don’t feel any emotion.

After discharge from the hospital, he went to Lake Como, north of Milan, to guard German prisoners for two to three months. That was a more relaxed, happy time. But it didn’t last too long.

An order came: They are going to be sent to fight the Japanese. The war in Japan was still going on. They had very mixed emotions.

“Here we are, Japanese Americans. To fight with Japanese soldiers, they could be my cousins. Emotionally, [it was] very hard.”

The training had already begun.

Fortunately, he didn’t have to go. The war between Japan and the US ended.

Five years ago, the Takahashis went to the memorial in Washington D.C. commemorating Nikkei soldiers. He had an emotional experience.

“Even like me with a Silver Star, I just don’t want to talk about it. Recently, a thirteen year-old son of a nephew wanted to learn about it. I just sent him a box (of the memories).

“What made you feel okay to talk about it,” I asked. Mitsuru talked about his Chinese best friend from the elementary school, whom he didn’t dare see for several years after the war.

“I wanted to go see him but wasn’t sure if he would see me as a JAP. Would he be glad to see me?”

Finally, they got together and that fear went away.

“Does the American public accept us?”

His friend understood but there was still that bitter feeling toward Japanese Americans and discrimination was in the mist.

In the Mount Baker area, a real estate agent told him, “I’d like to sell you a house but I’m sorry, I can’t. I’ll lose my job.”

Takahashi recalls that it was a hard time emotionally, readjusting from the evacuation.

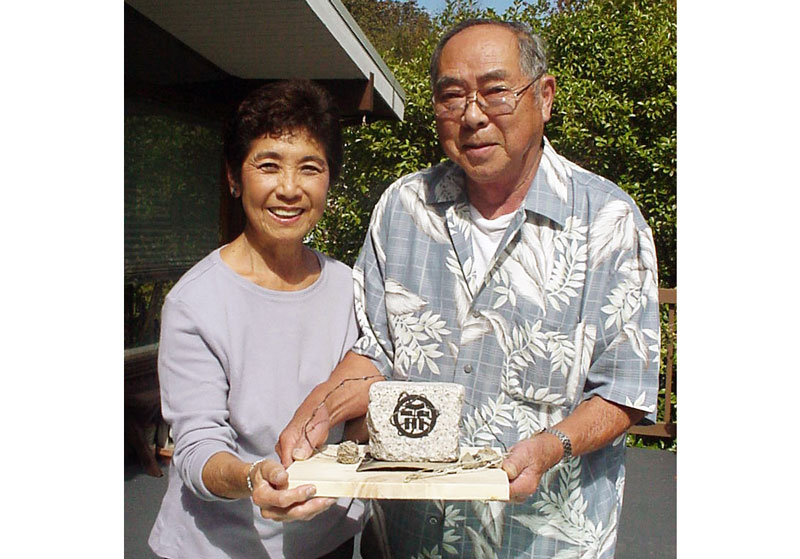

Yet, even during the hard times, June was always there for him with a smile. Last month, the two went to Minidoka for the pilgrimage. They were the only couple there rooted in Minidoka because that is where they met and became engaged.

They received a memento rock with a logo designed by artist Frank Fujii. The logo, which shows the Issei, Nisei, and Sansei wrapped by barbed wire also symbolizes the tie between the Takahashis. Mitsuru talks about the trip happily, but immediately changes his expression once the subject returns to the war.

“I’m very proud of what we did. Good soldiers, brave soldiers. The 442nd was a small unit, but [was the] most decorated unit. If they disgraced themselves, Japanese wouldn’t be as accepted as they are now today despite the discrimination we went through.”

His feelings reflect his complex emotions as an American of Japanese heritage. Last year, the Takahashis went to Japan and Mitsuru sat next to an old man with one arm on the way back to Seattle. He was a veteran of the Japanese army.

“He knew about the 442nd and said that it was a good thing that I didn’t disgrace the Japanese heritage. And I’m glad we didn’t.”

The man was very cordial and it was a compliment.

“That is the experience I want to never go through again but I’m glad I went. I’m glad I could serve the country (as an American),” Mitsuru added.

The stiff expression on his face reads as though he is still holding his emotions inside.

After 58 years, the wound in his shoulder is healed, but the pain that was cast over the teenage boy by the war may never go away.

Editor’s notes. This article, the seventh in the 13-article series, is reprinted from NAP-Northwest Nikkei, Sept. 27, 2003. The remaining interviews will appear monthly.

The hill-climbing battle was that to cross the Gothic Line, a German defensive wall that spanned northern Italy through the Apennine Mountains. As WWII is extensively documented online today, the interested reader can pursue how the 442nd Infantry’s actions there fit into the broader Allied attack, including detailed maps of troop positions. Such summaries provide “big picture” perspectives that would not have been available to common soldiers on the ground.