Epidemiological Research for the Health of Humankind

By Ayano Honda

Translation by Bruce Rutledge

Tsukasa Namekata, founder of the Pacific Rim Disease Prevention Center, has devoted the last 28 years of his life to researching the health of Japanese and Japanese Americans living in Seattle.

Tsukasa Namekata with (from left to right) his wife Keiko, eldest daughter Naomi and her husband, and second daughter Mayumi and her husband, followed by the grandchildren aged 4, 7, and 8. Namekata says he looks forward to babysitting his grandchildren more than anything these days.

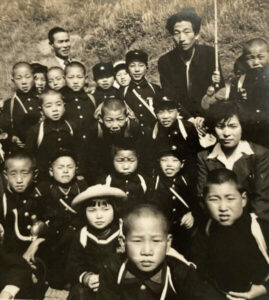

◀︎ A fifth grade field trip.

◀︎ A fifth grade field trip.

Namekata was born in Osaka, Japan in 1943,the second son of five sisters and brothers. His family was reasonablywell-off, but World War II was raging, and his father was killed in an air raidin Osaka in August 1945 when he was two years old. The family was evacuated tohis mother’s hometown in Yabukamimura, Minamiuonuma-gun (now Minamiuonuma City), Niigata Prefecture, Japan. After the war, life in the village remainedharsh, and Namekata says that he was often depressed. However, his life took aturn for the better after an encounter with his former teacher

“My fifth-grade homeroom teacher, Ken Ogawahelped me a lot mentally,” Namekata recalls. “He may have influenced my laterdecision to become a teacher. As I was encouraged by my teachers, I regained apositive attitude and gradually began to study harder.”

Namekata demonstrates a pike jump on a vaulting horse. During his college days, he spent his time studying, participating in the gymnastics club and working as a part-time tutor. Photo courtesy of Tsukasa Namekata.

In his third year of junior high school, Namekata decided to go on to high school. He and two friends studied hard from 7:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. Out of 100 classmates, only five went on to high school. “In a village centered on agriculture, only a few people graduated from high school in those days,” he says. “In my case, I was greatly influenced by my older sister, who graduated from high school before me and went on to Niigata University.”

He entered Ojiya High School, but it took him two hours each way to get to school. It was an hour’s walk from his house to the nearest station, followed by an hour on a slow train. “I remember I was very tired and had a hard time studying because I had to eat after I got home,” he says. After graduation, he entered the Faculty of Education at Niigata University to become a teacher of health, physical education and mathematics at junior and senior high schools.

What was it that drove him to become a researcher?

“My university graduation thesis on the health of village children was the starting point of my life as a researcher,” he says. “The village where I lived is in one of Niigata’s heaviest snowfall areas. In Japan, during the postwar 1945 and economic reconstruction period, fresh vegetables, meat and fish were almost never available for us until the snow melted. I wondered if the physique and physical strength of village children were inferior to that of their city counterparts.”

Namekata immersed himself in research for a year of survey data and statistics on more than 300 students at Yabugami Junior High School. Namekata could not forget the sense of fulfillment and satisfaction he felt when he finished writing his graduation thesis. After consulting with his advisor, he decided to apply to graduate school at the University of Tokyo, Japan. “I was not surprised to learn that no one from Niigata University had entered that laboratory in the past. After finishing my part-time job as a teacher at a regular high school, I spent my days frantically studying until around 4:00 a.m. I was confident in my physical strength, which I had cultivated through exercise, but I would oversleep when I got into bed so I would sleep on the tatami mats,” he recalls with a laugh.

In the laboratory of the University of Tokyo graduate school where he was accepted, large electronic calculators were used. His first mission was to master Fortran IV, the most advanced programming language at the time. There were still very few people who could handle large computers, and this experience would give him an advantage when he later found a job in the United States.

A turning point came in 1970, when he received a call from a graduate school at the University of Illinois in Chicago inviting students to apply for a position. First, he had to pass a TOEFL test for English proficiency to be eligible to study abroad. He studied for that test for a year. His stoic, tenacious character played a role here. However, after getting accepted for the position, he had not even considered how much airfare would cost. Luckily, he was given a ticket on a chartered airplane provided by the Foundation for International Educational Cooperation.

Dr. Tim Nugent,Director of the University of Illinois’ Rehabilitation-Education Center, with his wife, Mrs. Jeannet

Dr. Tim Nugent,Director of the University of Illinois’ Rehabilitation-Education Center, with his wife, Mrs. Jeannet

Nugent, (l) Keiko, who later became Mr. Namekata’s wife in 1971. Photos courtesy of Tsukasa Namekata. ▶︎

In 1971, when he moved to the U.S., a new stage in his life began. In exchange for minimal living expenses and a tuition waiver, he worked 20 hours a week on campus as a physical therapist’s assistant at a rehabilitation center. There, he met Keiko, who later became his wife. “My wife was blind from congenital retinopathy and volunteered at the rehabilitation center to help new blind students,” he says. “In 1972, she was invited to the (U.S.) White House to participate in a special award ceremony for the nation’s outstanding blind students. We were married while in school. She was very helpful in helping me keypunch thousands of IBM data cards for my doctoral dissertation research.”

◀︎ Namekata’s graduation thesis was

◀︎ Namekata’s graduation thesis was

later published by the Japan School

Health Association. Photo courtesy

of Tsukasa Namekata.

After receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Illinois Graduate School of Public Health, he was accepted as a research assistant at the university’s School of Public Health There, he participated in a project to study the relationship between air pollution and respiratory diseases in Chicago. He studied the number of patients with asthma, chronic bronchitis and other respiratory diseases in the city’s hospitals and analyzed associations with air pollution. One year later, when he became an assistant professor, Namekata fulfilled his former dream of teaching. He taught courses on the health hazards caused by pollution, and he urged his students to never allow such things as Yokkaichi asthma, Minamata disease and Itai-itai disease (pollution-related diseases that occurred in Japan) to happen again.

Winters in Chicago are cold. Namekata became concerned about the health of his eldest daughter, who often caught colds. Although he had been steadily building his career, he began to think about moving to a warmer climate. Then he found a job opening for a research scientist at Battelle Memorial Institute in Seattle, Washington and jumped at the chance. He got the job and moved to Seattle in 1980.

In 1983, he received professional recognition as a Senior Research Fellow in Epidemiology from the American Academy of Epidemiology. The following year, he accepted the chairmanship of a workshop of the International Society for Epidemiology held in Vancouver, Canada.He addressed the issue of respiratory diseases and related compensation due to air pollution in Japan. The results were published by Battelle Press. In the U.S., researchers are under constant pressure to propose their research to the government and research foundations to obtain funding. While participating in numerous academic conferences and projects, Namekata says he also experienced firsthand the harshness of the world of academia.

In 1989, while still at the institute, he founded the Pacific Rim Disease Prevention Center. “I was concerned that a large research institute would have huge administrative costs that would be taken out of the research budget, and I was worried that I would not be able to continue my research to my satisfaction,” he recalls. “With a smaller foundation, administrative costs would be less. I wanted to concentrate on research on the health of Japanese and Japanese Americans living in Seattle, so I decided to start a foundation with the consent of the Battelle Memorial Institute and the cooperation of the surrounding community.”

In November 2019, a reception was held at the Suigetsu Hotel Ogaiso in Ueno, Tokyo, for all concerned to express gratitude for Mr. Namekata’s work. Photo courtesy of Tsukasa Namekata.

In November 2019, a reception was held at the Suigetsu Hotel Ogaiso in Ueno, Tokyo, for all concerned to express gratitude for Mr. Namekata’s work. Photo courtesy of Tsukasa Namekata.

The Namekatas pose with Mr. and Mrs. Edward Perrin at an event at Nisei Veterans Committee Memorial Hall for the closure of the Pacific Rim Disease Prevention Center. Mr. Perrin was Mr. Namekata’s boss at the Battelle Memorial Institute and professor emeritus at the University of Washington. Photos courtesy of Tsukasa Namekata.

The idea for this health survey originated from a desire to bring to Seattle a network of health checkups like those done by the Japan Health Promotion Foundation. During a visit to Japan, he succeeded in obtaining full cooperation from Kenji Suzuki of the Japan Health Promotion Foundation. The Seattle location for the checkups was also made available through the remodeling of the second floor of the building owned by Dr. Evan Shu and Dr. Ruby Inouye, one of the directors of the foundation. The results of the study are available as a computer PDF software file on the official website (www.seanikkeihlth. com) under the heading “Summary of 30 Years of Health Research on Japanese and Japanese Americans.”It examined the relationship between the environment and health of the community by comparing the health examination data of Japanese and Japanese Americans in Seattle with the data of the Japan Health Promotion Foundation. It is due to Namekata’s passion and personality that this valuable research on Seattle’s Nikkei (Japanese American) Community took shape through the connections of so many people.

After retiring from the Battelle Memorial Institute in 1992, Namekata continued to pursue these research activities as director of the center and served as an associate clinical professor at the University of Washington School of Public Health. In 2016, he decided to retire. Along with his retirement, the Pacific Rim Disease Prevention Center closed its doors.

Since then, Namekata has remained active, serving as president of the Seattle Hiroshima Kenjinkai. He leads a busy life, tending to his garden, taking walks with his wife and babysitting his three grandchildren. “I also started playing pickleball to maintain my fitness,” he says. “Next, I have to deal with all the research materials and books I have accumulated!”

◀︎ A fifth grade field trip.

◀︎ A fifth grade field trip. Dr. Tim Nugent,Director of the University of Illinois’ Rehabilitation-Education Center, with his wife, Mrs. Jeannet

Dr. Tim Nugent,Director of the University of Illinois’ Rehabilitation-Education Center, with his wife, Mrs. Jeannet ◀︎ Namekata’s graduation thesis was

◀︎ Namekata’s graduation thesis was In November 2019, a reception was held at the Suigetsu Hotel Ogaiso in Ueno, Tokyo, for all concerned to express gratitude for Mr. Namekata’s work. Photo courtesy of Tsukasa Namekata.

In November 2019, a reception was held at the Suigetsu Hotel Ogaiso in Ueno, Tokyo, for all concerned to express gratitude for Mr. Namekata’s work. Photo courtesy of Tsukasa Namekata.