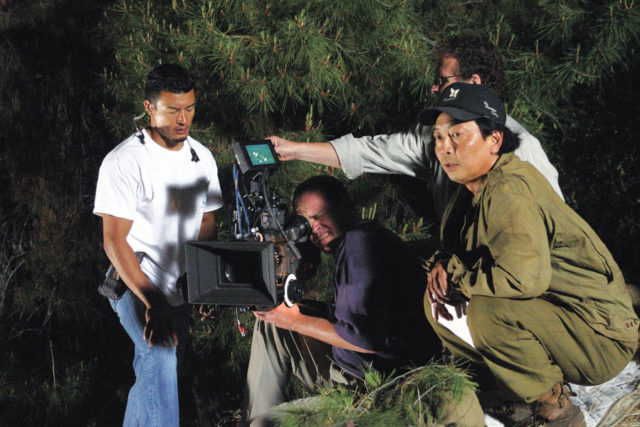

A Compelling Voice & Thoughtful Storyteller

Actor & Filmmaker, Lane Nishikawa

by Bruce Rutledge

Lane Nishikawa is a poet, playwright, actor, filmmaker, and arts activist. He was born in Wahiawa, Hawaii, but was raised mostly in San Francisco. He graduated from San Francisco State University with a degree in Asian American Theater. His three one-man shows, “Life in the Fast Lane”, “I’m on a Mission from Buddha”, and “Mifune and Me”, toured to over 50 cities across the US, Canada, and Europe. “I’m on a Mission from Buddha,” was produced for television in San Francisco and had a National PBS broadcast. Nishikawa’s first feature film, “Only the Brave,” tells the story of the 100th/442nd Regiment’s rescue of the “Lost Battalion”, Texans of the 141st Regiment, who were trapped by the Nazis, in the Vosges Forest in France, in October of 1944. His most recent work, a documentary about the effects of war on the Japanese American community, called “Our Lost Years,” will have a special screening in Seattle at the NVC Memorial Hall on the afternoon of February 29.

Lane Nishikawa has used film, stage, and written word at various stages of his career to probe what it means to be Asian American and Japanese American. Oscar-winning film director Steve Okazaki called him “one of Asian America’s most compelling voices.” The Hawaii-born artist will be bringing an important documentary to Seattle later this month. His film “Our Lost Years” will be showing at the NVC Memorial Hall (1212 S. King Street, Seattle) on February 29 at 2pm and at Kent Lutheran Church (336 2nd Ave S, Kent) on March 1st at 2 pm. The screening in Seattle is sponsored by the NVC Foundation and co-sponsored by Densho and the Seattle Chapter of Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). Nishikawa will be in attendance. The screening in Kent is sponsored by the Puyallup Valley JACL, White River Buddhist Temple, Greater Kent Historical Society, and the Kent Grand Organ Project. Lane will attend at both events and will conduct question and answer sessions following the film.

“Our Lost Years” revisits the forced removal and mass incarceration of 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II. Nishikawa traveled to seven cities to interview internees, their children, and grandchildren about the collective trauma of that dark period of US history. He also interviewed politicians, community leaders, lawyers, and activists. Nishikawa takes a deep look at the psychological impact of incarceration, the battle for redress and reparations, and the newfound voice of the Japanese American community reminding fellow Americans to remain vigilant in the current political climate.

“I spoke with politicians, community leaders, the Council of American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), and the Anti-Defamation League,” Nishikawa told us during a phone conversation from his San Diego home. “We had a limited budget, but we set out to look at not just internment but before the war, through the evacuation, the return home, and onto the next generation and the fight for redress and reparations.

“Our Nisei parents and Issei grandparents didn’t talk about the internment,” he says. “It was a painful time, and they lost a lot. There was a lot going on in terms of silence. We Sansei would hear about the camps and think it was like summer camp. It wasn’t until the redress movement was under way that we were able to give them a voice.”

Nishikawa grew up in the Bay Area and was very active in the theater scene there. He came of age during the heyday of Asian American theater and ended up with a degree of his own creation in Interdisciplinary Studies ― Asian American Theater, which blended classes in creative writing, ethnic studies, and theater at San Francisco State University.

During his student days, he went to see plays put on by the Asian American Theater Workshop. The plays about Asian American lives opened his eyes. He was writing poetry at the time in what would now be called “spoken word” format. He soon began performing at the annual street fair in San Francisco’s Japantown and elsewhere, writing one-man plays that explored Asian American life. His first one-man show, “Life in the Fast Lane,” debuted in 1985. In it, he explored the barriers an Asian American writer faced in getting published. The show was set up in an interview style. Lane answered questions from an imaginary TV host and performed vignettes in between the questions that explored themes like growing up in a black neighborhood, seeing the ghost of a 442nd soldier, and hearing a bigot talk about his daughter marrying an Asian guy. The show was a big hit. “We performed it in something like 50 different cities. We toured it through the U.S., Canada, and Europe.”

Meanwhile, Nishikawa took the helm at the Asian American Theater Company in 1986, becoming its artistic director. He held that position for ten seasons. “During that time, we developed a lot of producers and directors,” he says. “We supported a lot of new playwrights.”

Nishikawa’s second one-man show was ”I’m on a Mission from Buddha” in 1991, a biting satire about the plight of Asian American actors trying to get mainstream roles in a land where “American” means “white.” “In theater, film, or TV, nobody would cast you,” he says of that time. Nishikawa played 18 different characters in the 90-minute play, from a Japanese rapper to a sushi-hating redneck.

The inspiration for that play, Nishikawa says, was being the lead in so many projects in San Francisco, and then going to Los Angeles for auditions and being given just one line to say. “‘Let me take your blood pressure. That bullet came pretty close to an artery.’ That was it,” he says.

“I’m on a Mission From Buddha” was adapted for television at KQED and had a national broadcast in 1993. “Something like 200,000 people in the Bay Area alone, saw it”, he recalls.

In his third one-man show, “Mifune and Me,” Nishikawa explored his fascination with Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune. “My grandfather was from Japan. He loved Mifune,” Nishikawa says. “I realized I had a Japanese face, but I would never be able to be a Mifune in America.” The show examined images of Asian Americans in the media over the past 150 years.

Nishikawa received rave reviews for his next work, “The Gate of Heaven,” a 1996 play about a Japanese American soldier liberating a Jewish prisoner from the Dachau concentration camp.

Nishikawa eventually turned to film, producing several shorts before releasing the feature length “Only the Brave” in 2006 about Nisei soldiers in the 442nd regiment. That group of soldiers has a special place in Nishikawa’s heart. “I had seven uncles who served in the 442nd and the MIS,” or military intelligence service, he says. “Most had passed away when I was making this film. Only one was still alive. My dad was training as a replacement, but his appendix burst and had to spend six months in the hospital. By the time he got back in shape, it was 1945, and the US could sense that the end was coming, so he never got deployed to join his brother. He ended up as a Staff Sergeant of an MP unit in Germany.”

Nishikawa worked hard to make sure as many people as possible saw his movie. “I spent 10 years working on distribution for that film,” he says, “and trying to find funding for another feature. It was very difficult.” He finally decided to try a documentary approach and received a grant from the National Park Service – Japanese American Confinement Sites Program to help him on his way. Nishikawa says, “The San Diego Chapter JACL served as my fiscal sponsor and was a tremendous help with our fundraising.”

The film features interviews with former Secretary of Transportation Norm Mineta, former Congressman Mike Honda, author John Tateishi, and many other luminaries of the Japanese American community. Nishikawa made a point of including relevant perspectives from outside the Japanese American community, most notably Hanif Mohebi, former executive director of the Council of American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) San Diego, and Amanda Susskind, regional director of the Anti-Defamation League.

Nishikawa makes a point of using humor even in the darkest moments, which makes his art more approachable and memorable. “The more specific you get, the more universal your work is. I want to capture the highs and lows. Humor helps with that,” he says. “Like the story of a cook in the camps who grew up on a chicken farm and could cook chickens. At Thanksgiving, he undercooked the turkeys, people were running to the bathrooms, and he lost his job! Or the woman who said her father had to sell his car for $15, but then remembers, but it was an old car.”

While humor helps, Nishikawa has never been one to sugarcoat reality. “Susskind talks in the film about the Pyramid of Hate. First there are racial slurs, then physical attacks, then government action.” He worries that we are climbing that same pyramid again today. His description of “Our Lost Years” drives home that point. It “provides a lens into the bridge between generations, the bond between families, the loyalty to one’s country, the passion with which one fights for those they love, the loss and sadness of a terrible period in our history, and the unquestionable faith of a community to persevere and overcome whatever obstacles they faced. Executive Order 9066 was a dark decision during a troubling time in our nation’s history. We owe it to future generations to never forget and ensure that it never happens again to any race, to any community, and most importantly, to any American.”

Nishikawa adds, “I want my work to change opinions about who we are. That’s the thought behind ‘Our Lost Years.’ It’s not a film just for Japanese Americans. I want all Americans to watch it, because it is an American story.”

“Our Lost Years” – Screenings in the Seattle area

February 29, 2 pm at NVC Memorial Hall, 1212 S King St., Seattle

sponsored by the NVC Foundation and co-sponsored by Densho and the Seattle Chapter of JACL

Info: https://www.nvcfoundation.org/newsletter/2020/1/special-event-our-lost-years/

March 1, 2:00 pm at Kent Lutheran Church, 336 2nd Ave S, Kent

Sponsored by the Puyallup Valley JACL, White River Buddhist Temple, Greater Kent Historical Society, and the Kent Grand Organ Project

Info: http://kentlutheran.org/klc/our-lost-years/