By Aya Ito, Japanese Cultural & Community Center of WA Ganbaru Intern

The article was originally published by in Japanse Cutural & Community Center of Washington, jcccw.org

In 1930, there were more than a hundred hotels in Seattle’s Japantown, according to Hokubei Jiji (The North American Times) 1936 edition year book. The Panama Hotel was one of them. In the 1920s, many single men stayed at the hotel when they didn’t have their seasonal jobs. There was a large public bath inside the Panama Hotel. For many Japanese immigrants, it was the place where they could come, relax and talk to each other. However, during World War II and after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which forced Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans living on the West Coast to move to concentration camps in desolate locations. Even though people born and raised in the U.S. who were American citizens, they had to go to the concentration camps because of their Japanese ancestry. People were limited to a few items when they moved to these camps. With that, people had to sell or give away their cars, furniture, homes and personal belongings.

Jusaburo Fujii was running a Chinese restaurant in Japantown during the period, and he asked Takashi Hori, who was the owner of the Panama Hotel, if he could store his stuff while they were living in the camps. Knowing about Mr. Fuji’s request to Mr. Hori, other Japanese immigrants also asked Mr. Hori to keep their belongings at the hotel during the war. Therefore, the Panama Hotel became a quasi warehouse for Japanese immigrants. Panama Hotel has such a significant historical value, but quite a few people do not know what happened to the Nikkei people because of lack of access to the information.

Yuri Hikita started her internship at Panama Hotel tea and coffee house (Panama Cafe), located on the first floor of the Panama Hotel a year ago. The cafe displays many historical photos and pictures, and surprisingly, Japanese immigrants’ belongings still remain in the basement. There is even a novel called “Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet” by Jamie Ford, that is set in this hotel, which was on The New York Times’ Best Sellers List in 2009. Since Hikita started research about the history of the hotel, she thought there must be more intriguing facts that people never knew.

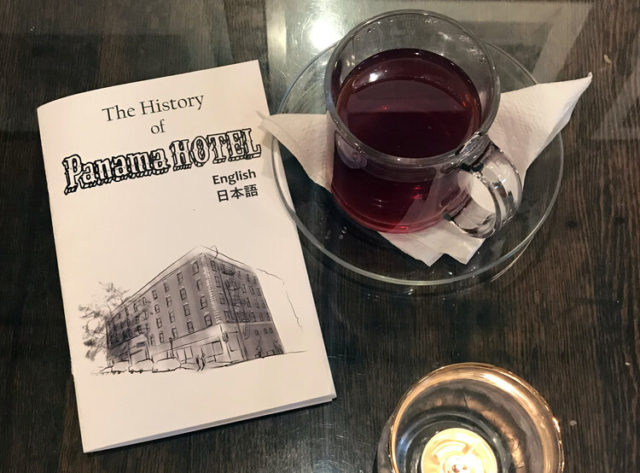

Spending significant time at the Panama Cafe, Hikita realized if more information was accessible, it would be helpful for customers because some of them have already read the novel and frequently have asked her “Is there any kind of official booklet?”

Those inquiries encouraged her to work on finding and compiling a helpful resource of the historical site.

“I was overwhelmed by the amount of information I got from items in the basement, including photos and pictures, which we can’t get from the internet. I did so much research and got in contact with Ms. Susan Hori, who is the daughter of Mr. Takashi Hori. Once I started to talk to her, I thought this should be known to more people. For me, it is not just a task, but more like a mission.” In December, most pictures in the cafe were researched and people, dates, and locations in these images were identified. The research and text was proofread and printing has been done by supporters.

The official booklet is going to be on sale at Panama Cafe at a cost of $17.00, with a limited 100 books being printed. The sales are going to be used for maintenance costs for the Panama Hotel.

Hikita added, “The mistake of Japanese-Americans being interned in the camps was driven by fear, lack of information and racism. Though it has been over 70 years since WWII, the current situation all over the world has not changed at all. Fear leads people to make terrible, inhumane decisions. The most important thing is that we have to be aware of that.” Yuri said. “I hope this booklet can become one of the triggers to think about and look into what’s happening today carefully.”

The Panama tea and coffee house recently finished adding labels to each historical photo of the Japanese community in Seattle and other neighborhoods of post WWII. Some of them are related to the booklet so you can take a look at the images of 1920s and 1930s.