By David Yamaguchi

The North American Post

These past few months, I have gotten to know something of Kenichi “Ken” Sato. Like many readers, I have known Mr. Sato’s name for years from its association with the Japanese Community Service, the group of elders who administered the Seattle Japanese Language School from its dawn of time through the handover of the school and grounds to the present Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington. Until not long ago, he was the unusual Nisei who would be called on to read a bilingual haiku poem at a community gathering. Until recently, however, I had not ever sat down to talk with Mr. Sato in person.

To visit the Sato home is to see what men used to be like. The wooden hand railing leading from the driveway up to the porch sets the tone. It is the charming imperfect work of a homeowner, not that of a professional carpenter.

In the living room, guests sit on couches that are homemade. On the windows are shoji screens that slide in neat wooden grooves. A daughter proudly points out that Mr. Sato made these as well.

Unless questioned, Mr. Sato, speaks little of his own life, letting his wife, Sarah, converse instead.

The broad strokes, however, gleaned from several conversations, are that the Maui-born and raised Mr. Sato has lived a remarkable life. The standout years begin with his work as a translator for the U.S. Army in post-war Japan.

For part of this time, Mr. Sato was stationed at Maizuru, on the Japan Sea, interviewing Japanese soldiers repatriating from the Asian mainland. Later, he interpreted for minor war-crime trials in the Philippines.

When his army service ended, Mr. Sato continued translation work in Japan as a U.S. civil servant. The demand for linguists was great, as Japanese was also useful for interviewing Korean soldiers. They spoke Japanese owing to Korea having been annexed by Japan in 1910.

It was the September 1950 enrollment deadline on GI Bill funding of the college educations of WWII-era veterans that prompted Mr. Sato to return to his former life as a student at the University of Hawaii. He had completed one year of study there before being drafted in June 1945. After marrying Sarah, he transferred “overseas” once more to attend the University of Washington.

As a UW student, Mr. Sato first lived at SYNKOA House, the Issei-purchased home for UW Nisei students. Nisei were not welcome in the UW fraternity system at the time. The name of the historical home comes from the names of UW Nisei who were killed in combat during WWII. There, Mr. Sato began learning the business that he would end up teaching over his career with the Seattle Public Schools.

In addition to his day job, when Sarah quit her job at the Washington State Health Department to raise the kids, Mr. Sato began teaching classes at night at North Seattle Community College and elsewhere, to make up for the reduced monthly income.

In the 1980s, Mr. Sato began his association with the Japanese Community Service. The Issei who ran the organization in those days were glad to have the younger bilingual man join them, as their board meetings were conducted in Japanese. After retiring, Mr. Sato spent every Saturday for ten years as a volunteer “whatever they needed” everyman at the language school. Notably, Mr. Sato was the person at the helm of the Japanese Community Service through the handover of the school to the broader-missioned cultural center. He received a kunsho award from the Japanese government for his lengthy service on behalf of the school.

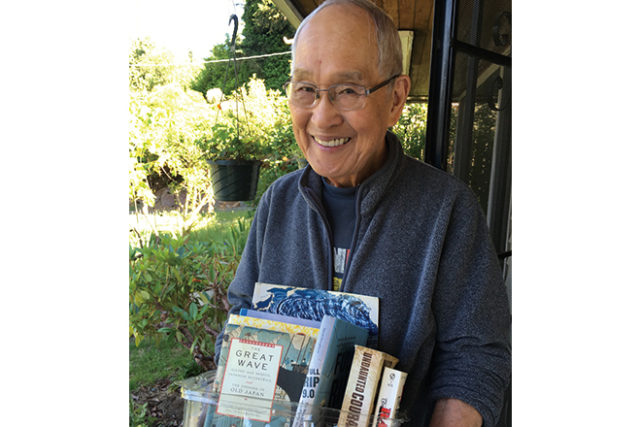

These days, Mr. Sato spends his time reading and working in his garden. His home, however, is not serene. For over several visits, one cannot help but notice how family members are always bopping in. There are the two daughters who tinker weekly—cleaning out the refrigerator, painting bedrooms. There are the grandchildren who come to lend a hand and to hang out.

To the amusement of Mr. Sato’s daughters, when 5 PM arrives, he sits down at the dining room table, to see what will appear—by magic—for dinner. In this way, especially, he is like the Japanese men of old.

Overall, Mr. Sato is the kind of man all men would all like to be at 90. He is reasonably healthy and happy. He has lived a balanced, exemplary life, in service of his country, his family, and his community. He is surrounded by children and grandchildren.

To highlight lives like Mr. Sato’s here matters because it reminds us of what is possible. It shows how ordinary men laid the foundation for the smooth U.S.-Japan relationship we have today. Locally, it shows how it is that there was a still-functioning language school with buildings and grounds when planning began for the Japanese cultural center.

To the fathers out there, and to others who just want to be better men, Happy Father’s Day!

P.S. A more complete biography for Mr. Sato is at the Nisei Veterans Committee and Foundation website, <nvcfoundation.org>.