Interview by Elaine Ikoma Ko, Special to The North American Post

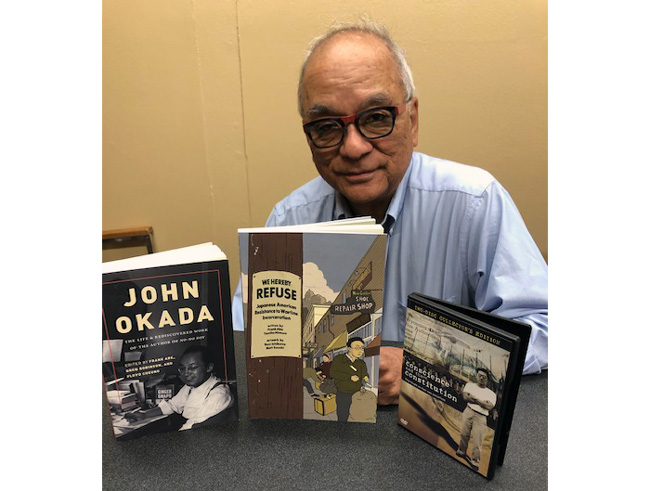

After a successful media career, Frank Abe has produced acclaimed literary and film works on resistance to Japanese American incarceration — a living legacy more relevant than ever today. His latest contribution is a graphic novel, “We Hereby Refuse” (2021), a comic-book format that is anything but a funny book. Below, we explore why this book has found such a receptive audience, its connection with the classic novel “No-No Boy” (1957), Frank’s biography of the novel’s author, “John Okada” (2018), and why so many locations in Seattle are part of this history.

Frank Abe is a former reporter for KIRO Newsradio and more recently served as communications director for King County Executive Dow Constantine. He won an American Book Award for “John Okada: The Life and Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy“ (University of Washington Press, 2018). He also wrote and directed a PBS film on the largest organized resistance to incarceration, “Conscience and the Constitution” (2000, 57 min.). He is currently co-editing a new anthology for Penguin Classics on “The Literature of Japanese American Incarceration.” He blogs at Resisters.com.

Let’s start with the beginnings of your 40-year odyssey to reframe the incarceration experience — beginning with your father’s detention in Seattle.

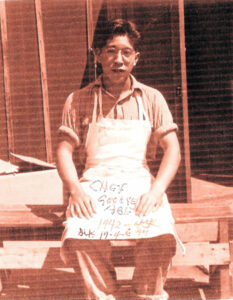

My Kibei-Nisei father, George Abe, was just 13 when he was sent alone from Japan in 1937 to work on a walnut farm near San Jose, California. He was taken off the ship and held for three weeks of interrogation at the Immigration Station and Assay Office here in Seattle.

He was always grateful to an immigration translator named Jack Yasutake, who overlooked the sketchy details of my father’s passport, sprung him from detention, and brought him home to Seattle’s Beacon Hill for dinner and a nice Japanese bath with the Yasutake family. He must have met the Yasutake’s daughter, renowned poet Mitsuye Yamada.

The next morning Mr. Yasutake took him down to King Street Station and put him on the train to California. My father was still a teenager alone in America when he was put on another train in World War II, first to the Pomona Assembly Center and then on to the camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

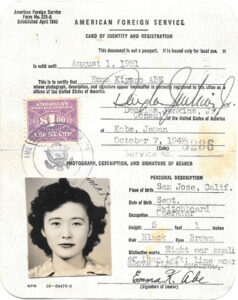

I had no business being born in Cleveland, Ohio, but that’s where a War Relocation Authority officer sent my father for resettlement after the war. My mother, Emma Kiyono Abe, was sent from the same village in Japan to Cleveland to join him there. My father moved us back to San Jose when I was ten. He worked as a landscaper and my mother as a dental technician.

With Seattle now my home, King Street Station is my emotional anchor to the place where my father’s journey here began.

How did you begin your media career and how does it relate to your strong interest to tell the Japanese American incarceration story?

An acting job brought me to Seattle in 1976, then I sought out an entry-level job at KIRO Newsradio because I wanted to learn how to write, and radio relies upon the spoken word and the ability to convey a story in 30 seconds.

Before that, I started as a stage actor in San Francisco with Frank Chin’s Asian American Theater Workshop, around the time that he, Shawn Wong, and Lawson Inada were establishing the field of Asian American literature as the Combined Asian American Resources Project, or CARP. They introduced me to a history in America we were all discovering at the same time. The injustice of wartime incarceration was only beginning to be understood. The only reliable books were by Roger Daniels and Michi Weglyn. The rest we had to piece together from oral histories.

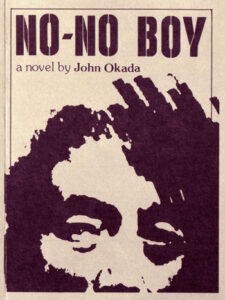

But there was one novel that CARP found in a used bookstore, the story of a Nisei draft resister from Seattle called “No-No Boy” by John Okada. That book revealed something raw and authentic about what really happened to Japanese Americans in Seattle as a consequence of expulsion and incarceration. And it started me on the path I’ve carved ever since.

Photo Nancy Wong

Why did you choose to develop your most recent book, “We Hereby Refuse,” as a graphic novel?

With a graphic novel you can gallop through a story with the epic sweep of a movie, while the visuals draw readers into the personal stories in a way that generates empathy. The Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience (“The Wing”) understood this when they conceived this project and secured a grant from the National Park Service for a series of three graphic novels, of which this is the second.

I’m glad to see that the book has found its audience. It’s been described as a “page-turner” by critics, and by educators as an effective tool for teaching the overall camp experience. I’ve sent copies to friends who’ve had them intercepted by their 7- and 12-year-olds.

How were the book’s three protagonists selected?

The Wing’s call for proposals offered a chance to expand the stories of camp resistance, like a miniseries version of my documentary “Conscience and the Constitution.” I proposed seven storylines and we winnowed them down to the three we used.

Mitsuye Endo’s habeas corpus case represents the four Supreme Court challenges and offered the chance to investigate her personal story, as well as present the story of a strong woman that can be taught in classrooms.

Hiroshi Kashiwagi gave us the chance I’d long wanted to reframe the maddeningly misunderstood story of segregation and renunciation at Tule Lake.

Hajime Jim Akutsu covered the draft resistance while enabling us to include the Seattle locations.

Were the three protagonists part of a broader resistance movement of hundreds of Japanese Americans who defied the unconstitutionality of their incarceration?

Yes, and by weaving these three stories along the single timeline of incarceration, they come to represent the collective voices of all those who objected to their ongoing imprisonment. Each takes a different approach, but their actions all come from the same place and give voice to the feeling of “This is wrong. We shouldn’t be here!”

That collective voice is the “We” in the book’s title.

What is the role of women in this history? Much is written about the men who were imprisoned for their stances against being drafted from camp, but far less is known about the women — their heartbreaks, trauma, and struggles as mothers and wives.

When you read the letters from Hajime Jim Akutsu’s mother, written in Japanese, pleading for the return of her husband to their family, you see a woman in despair who persists in trying to reason with an unreasonable bureaucracy.

Mira Shimabukuro, in her book “Relocating Authority,” covered the flinty determination of 100 mothers at Minidoka who signed a petition to President Roosevelt insisting upon restoration of citizenship rights for their precious sons before sending them off to war. These were Issei mothers who were taking stronger stands than their sons against drafting them from camp.

As Fuyo Tanagi told her son Shig, “If you go to fight and die without first regaining your rights as citizens, then you’re dying for nothing.” Mrs. Tanagi was an English editor for the prewar “Hokubei Jiji” (“North American Times”) newspaper, the precursor to today’s North American Post.

Shig Tanagi lived with wife Fay in Seattle’s Rainier Beach area until 2020. He helped with photos and memories of his mother that we used in the book.

Why this book and why now?

It seems to take a generation to work uncomfortable ideas that begin on the margins into the mainstream.

Until the 1990s, Japanese American resistance was not a subject for polite conversation. It was only 20 years ago when “Conscience and the Constitution,” my film on the Heart Mountain draft resisters, appeared. Other books and films were made around the same time. They helped break the ice.

The result is that younger Nikkei have grown up with the story of camp resistance as an accepted part of their history. When The Wing got the grant to produce three graphic novels on the incarceration experience, it was only natural for them to commission the story of camp resistance as one of them.

“No-No Boy,” published in 1957 by John Okada, is widely recognized as a classic of Asian American literature. Please describe the connections of this classic with your current graphic novel.

In my biography of John Okada, I confirm once and for all that draft resister Hajime Jim Akutsu was John’s inspiration for the draft resister Ichiro Yamada in “No-No Boy.” Hajime was the name Okada originally gave for Ichiro.

Both their fathers were arrested by the FBI on the same day, February 21, 1942, and held in the same immigration station as my father, five years earlier. The families of both wrote anxious letters from the Puyallup Assembly Center to the U.S. Attorney General trying to reunify their families.

In the preface to “No-No Boy,” Okada writes of a fictional radio signal interceptor in the belly of a B-24 bomber who is asked why he fights:

“I got reasons,” said the Japanese-American soldier soberly and thought some more about his friend who was in another kind of uniform because they wouldn’t let his father go to the same camp with his mother and sisters.

That soldier was Okada flying in a B-24 in Guam, thinking about Jim imprisoned at McNeil Island Penitentiary for his resistance. For me, this cemented their emotional connection and the decision to feature Akutsu as one of our protagonists in the graphic novel.

Your biography/anthology of author John Okada is an essential part of the “No-No Boy” story. It is described as the most comprehensive study of Okada and of his work. Do you agree?

We tried to cover all the bases, with the inclusion of Okada’s unknown play, short stories, and magazine satires, and the critical essays. It’s the first full biography which provides further insight into his writing of “No-No Boy.” It is actually the second book on Okada; the first was published by an author in Germany who reveres Okada’s work as much as anyone (Thomas Girst, “Art, Literature, and the Japanese American Internment: On John Okada’s No-No Boy,” 2015).

How were Hajime Jim Akutsu and John Okada linked to the many historical sites in Seattle?

Both were likely at King Street Station shouting goodbyes to their fathers as they were put on trains for the Department of Justice’s alien internment camp at Fort Missoula, Montana, wondering if they’d ever see them again.

After the war, Jim gets off a bus at Second and Main Street, upon his release from two years at McNeil Island, and walks past the clock tower of King Street Station. John would use that same scene for the opening chapter of his novel.

The two were neighbors at the Pacific Hotel, on 6th and Weller Street in Seattle’s Chinatown, and were drinking buddies at the nearby Wah Mee Club.

John Okada wrote as a nearly lone voice in 1957. If he had turned away from that, would we have ever been able to seek redress? Do you think it would have all been different?

Okada wrote what he knew to be true, whether or not it was accepted by an America that held up Japanese Americans at the time as a model minority, or by a Japanese America that embraced that stereotype. Whether or not his book sold, he said he was just glad to have it on the bookshelf for somebody, someday, to pick up and read.

Writing when he did in the mid-1950s, Okada could not even conceive of a day when the government would agree that the camps were wrong, much less actually apologize and redress its violations of the Constitution with a token compensation.

But redress would still have happened, because the pent-up demand for justice was too deep in our shared psyche – thanks to leaders like Edison Uno, Shosuke Sasaki, Henry Miyatake, and many others.

What are your next upcoming endeavors?

My co-editor on the Okada book, Floyd Cheung, invited me to help edit a new anthology of camp literature commissioned by Penguin Classics. We’re now furiously writing introductions and headnotes to our selections which include Okada’s first piece of creative writing: a poem he wrote just after Pearl Harbor in his family’s rooms at the old Yakima Hotel on Maynard Avenue at Dearborn Street, also in the International District.

After that, there’s a commission that will bring me back to my roots in live theater. So, the work never ends.