By Kazue Ito, Former Tokyo Correspondent for The North American Post

Translated by Michele Fujii

Editor’s note. Across recent months, we have been writing about the “North American Post’s” past, as we approach the 120th anniversary of its first publication as “The North American Times” on September 1. Recently, a series of 12 articles translated from the post-World War II Japanese-language “North American Post” has come to us from translator Michele Fujii, who did the work at the request of the Hibiya family. She believes it would be a shame not to share the translations more widely. While most articles are undated, the set begins with the January 1993 death of Takumi Hibiya, an Issei (first-generation immigrant from Japan). The writer is Kazue Ito, whose seminal work, “Issei, A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America” (Japanese Community Service, 1973, 1016 pp.; English version out of print) graces the bookshelves of many Seattle Japanese-American families today. We begin the series in this issue with its first article.

Japanese-American Media Biography by Kazue Ito

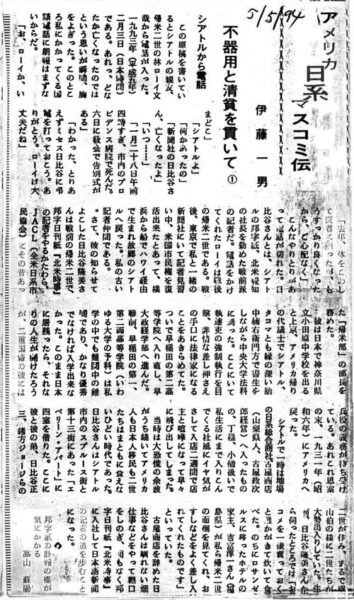

1. “Through Hardship and Lack of Ambition, A Call from Seattle” (NAP, May 5, 1994)

While writing (a) manuscript, I received a call from a close friend in Seattle, Roy Fumiya Hayashi, a second-generation Kibei (a Japanese American born in the US but educated in Japan). It was February 3, 1993 (Heisei 5). For some reason, I was momentarily struck by the thought that someone had passed away, since lately I hadn’t received any good news from an international call.

“Hi, Roy? Where are you?”

“Seattle.”

“What happened?”

“Mr. Hibiya from the newspaper passed away.”

“When…”

“January 28th, just after 4 a.m. He died at Providence Hospital in the city. There’s going to be a memorial service at the church on the 6th.”

“I see. I’ll send a telegram of condolence to Mrs. Hibiya straight away. Thanks. You’re doing all right aren’t you, Roy?”

“I went to see a doctor about my health last year, but I’m all better now. No need to worry.”

The conversation was along those lines. I hung up the phone. Mr. Hibiya had worked as a reporter and president of the Japanese language newspaper, “The North American Post” (Hokubei Hōchi), in Seattle since before the war.

Roy, who had just called me, was educated in Japan. After the war, while he was interning at the newspaper company where I worked in Tokyo, he was able to regain his United States citizenship. He then returned to his birthplace of Seattle by boat from Yokohama by way of Hawaii. He’s a former colleague.

Well, that Mr. Takumi Hibiya of whom Roy had informed me, was (also) a second-generation Kibei. While working as a reporter for the daily Japanese-language newspaper, “The North American Times” (Hokubei Jiji), (he also) served as the director of the former Kibei department of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL).

After graduating from Odawara Junior High in Kanagawa, Japan, (Hibiya) went to Tokyo and entered law school at Chūō University. While studying, he worked as a houseboy for Kusuemon Tainaka, a returnee from America and member of the Diet (the national legislature of Japan) who had deep ties to Seattle and Tacoma. (1) During his time there, (Hibiya) decided against becoming a lawyer after observing their underhanded practices and heartlessness. He went on to enroll in Waseda University’s second class preparatory academy for law, and entered the Department of Politics and Economics.

Before WWII, even among private schools, it was difficult to gain admittance to both Waseda’s first and second class preparatory academies (now called “college prep.”). Applicants had to be exceedingly intelligent.

If (Hibiya) were to remain in Japan, many opportunities would (have) been open to him, but obligatory military conscription was also waiting because of his dual nationality. Considering this, he returned to the United States in 1931 (Showa 6).

For a short time, he worked at the Furuya Company, owned by Masajirō Furuya (from Yamanashi prefecture) in Seattle, but he was treated as an apprentice and the corporate culture got in the way of his personal life. Two weeks after he had joined the company, he fought with the store owner and promptly walked out.

At that time, the aftermath of the Great Depression still loomed and it was a difficult time for Issei, Nisei and Americans alike. Hibiya rented four rooms in an apartment at Spruce Street and 13th Avenue in Seattle. He and his younger brother, Shōzō Hibiya, lived there along with George Ogata, another Nisei. The apartment was like a gathering place for the many Nisei who came and went.

When he was alive, Mr. Hibiya remarked that, “Whenever I bought a bag of rice and left it in the apartment, someone always came along and ate it. Yoshitomi Junichi (from Fukushima Prefecture), a hotel owner who later moved to Los Angeles, took care of us Nisei. He often brought sushi and other food to the apartment.”

After quitting Furuya, Mr. Hibiya took on a number of jobs he was unaccustomed to, such as farming, to make ends meet. Before long, he joined “The North American Times” and began his career as a reporter.

Houjishi no / fuhou no obashima / ga

kini kakaru

“Curious, I scan the Japanese newspaper for obituaries”

– Soyō Takayama (2)

Translator notes. (1) A houseboy was a student hired to do housework in exchange for living quarters while attending school. This system was somewhat antiquated from the 1890s on, as many students had begun to live in dormitories; so this type of situation would not have been as common as in the Meiji period (1868-1912). (2) Each article ends with a poem that is a haiku. These can deviate from the standard 5-7-5 syllable pattern by the addition of one syllable (here, 5-8-6).

Editor’s note. The poems are probably Issei-written, as such content abounds in the published pages of “Issei.”

Kazue Ito was a former Tokyo-based journalist. In the epilogue of “Issei,” he wrote, “As long as I live, I would like to continue the study of Japanese immigrants in America.”

Michele Fujii works in international education at Kansai University, Osaka. She holds a MA in Japanese language and culture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.