By Edward Echtle, For The North American Post

Editor’s note

September 1 marks the 120th anniversary of “The North American Post.” To mark this significant milestone, author Ed Echtle has researched the history of this newspaper and that of its pre-WWIII predecessor, “The North American TImes.” This article is the first of a three-part series that will continue monthly in August and September.

Introduction

In the nearly 150 years since the first Japanese came to the United States, generations have made America their home, raising families, building businesses and founding communities that both reflect their traditional values and embrace the promise of opportunities to better one’s lot in a new land. Among the institutions playing a key role in building Japanese American communities have been Japanese-language newspapers which spring up wherever a Nihonmachi (“Japantown”) begins taking root. As an important forum for sharing news and opinion, the newspapers have fostered community dialogue. They have helped recent arrivals find their way in a country that is often unwelcoming. They have provided an important link to the people and country left behind. In the Pacific Northwest, a few such newspapers have come into being, yet most were short lived. However, one early publication, the “Hokubei Jiji” or “North American Times” withstood numerous challenges and continues to the present as the “Hokubei Hochi” or “The North American Post.” It is thus the journal of record for Seattle’s Nikkei (Japan-descended) community.

Seattle Nihonmachi

In the last decade of the 19th century, Japanese immigrants made their way to the US in increasingly growing numbers. Before the 1890s, Chinese immigrants and sojourners made up an important labor force in construction and extraction industries in the US. However, a tide of racist hostility from whites led to exclusionary laws and mob violence, curtailing Chinese immigration. To fill the resulting labor vacuum, Japanese arrived on the West Coast, ready to work hard for opportunities to make their fortunes.

As a port city, Seattle was a key point of entry for many Japanese and an ethnic neighborhood formed on the south end of downtown, adjacent to the earlier Chinese settlement. Barred from living elsewhere by prejudicial laws, Seattle’s new Nihonmachi quickly became a relatively safe haven where new arrivals could live, find work, start a business, or socialize with others with a shared language and cultural identity.

By 1900, Seattle’s Nikkei population clustered along Mikado Street (now Dearborn Avenue) and created a thriving business and cultural center. While young men sought employment through labor contracting firms to secure work in sawmills, canneries, agriculture and construction projects, others began businesses including hotels, laundries, and restaurants. As the Nikkei population spread out to rural areas, Seattle became a supply point for Japanese throughout the region. Among the more prominent businesses, Furuya Company, founded in 1892, was a major importer of Japanese goods supplying the community as well as many non-Japanese clients.

Along with businesses, social institutions took shape, including the Seattle Japanese Baptist Church — founded by Rev. Fukumatsu Okazaki —and a Japanese chapter of the YMCA. Among the YMCA’s outreach efforts was the founding of Seattle’s first Japanese language newspaper, “The Report” in 1899. While short lived, its publication demonstrated a demand for a local news source that addressed issues important to the community.

In 1898, Seattle’s development quickened as a key supply center for the Klondike Gold Rush. As the city’s importance increased, a Japanese consulate established in Tacoma in 1895 relocated to Seattle in 1901. While the Nikkei population remained primarily male, a growing number of families made their homes in the city, made possible by arranged marriages through extended families in Japan. By 1902, the growing American-born Nisei generation necessitated the establishment of a Japanese language school.

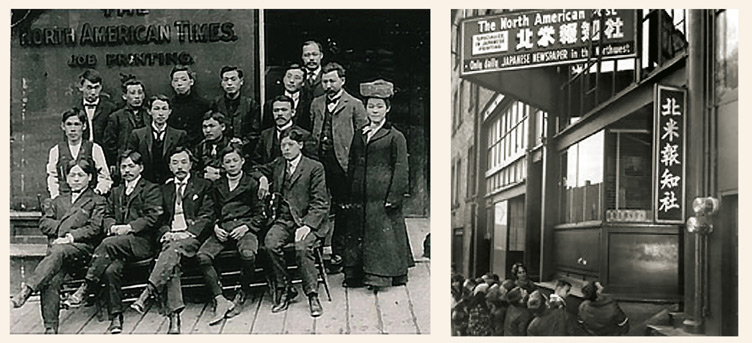

That same year, Issei (first-generation) investors Dr. Kiyoshi Kumamoto, Kuranosuke Hiraide, Juji Yadagai and Ichiro Yamamoto founded the “Hokubei Jiji” —“The North American Times” — in the basement of Hiraide’s bookstore, “Hiraide Shoten,” at 314 Jackson St. Edited by Sakutaro Sumigyu Yamada, the “Times” focused on local, regional, and international issues of importance to the area’s Nikkei community. The paper also prioritized community items such as obituaries, marriage announcements, and notices by families trying to locate relatives. The inaugural issue was published on September first. Not long after its founding, the “Times” moved to its own storefront office at 215 5th Avenue South (photos).

Left photo ddrdenshoorgddr densho 353 333

Over the next few years, staff at the “Times” worked hard to make it profitable. During this time, it had several editors in succession, including Yasushi Yamazaki, Senjiro Hatsukano and Fumio (Gyokudo) Aoyagi, and Shiro Fujioka. Among the stories receiving attention in the paper’s early years were the 1907 anti-Japanese riots in Vancouver, B.C. and the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” between Japan and US, intended to reduce out-migration of Japanese to the US. Local subjects included the construction of a new Japanese Baptist Church building and the opening of the Nippon Kan Theater in 1909 as a hub for community events and entertainment.

By 1910, Seattle’s Nikkei population was about 5,000 and the landmark Panama Hotel was completed in the growing business district along Main Street. Two Japanese language newspapers began publication in competition with the “Times,” the “Asahi Shimbun” (Morning Sun Newspaper) in 1905 and the “Taihoku Nippo” (“The Great Northern Daily News”) in 1910. To keep up with events beyond Seattle, the “Times” employed correspondents and opened offices in locations where other significant Nikkei populations resided including Tacoma, Spokane, Portland, San Francisco and Los Angeles.

By 1913, Dr. Kumamoto was the last remaining original investor. That year he decided to return to Japan, to assist his ailing father, and sold his two-thirds interest in the “Times” to Sumikiyo Arima and Shoichi Suginoo (G.S. Suginoh). Arima was born in Japan and had trained as a Presbyterian minister in Osaka before coming to the US in 1909. After earning a PhD at Oskaloosa College in Iowa, Arima traveled to Washington State and became a writer at the “Times’” Tacoma office. As the new publisher, Arima hired his 18-year-old son Sumiyoshi, recently arrived from Japan to attend Seattle’s Broadway High School, to share writing and editing duties.

Occasionally, items from the pages of the “Times” garnered interest from the English-language press, like when a severe storm damaged the newspaper’s storefront. In 1915, the publishers hosted a community celebration at the Nippon Kan Theater commemorating publication of the paper’s 4,000th issue, attracting many more well-wishers than expected. Three years later, the celebration for the publication of the 5,000th issue was held at Liberty Park (now Seattle University’s Championship Field.) Three thousand people turned out to partake in the festivities including Consul Naokichi Matsunaga and his wife, Tetsuo Takahashi of Toyo Trading Company, Imajiro Kudo and Tsuneyoshi Kikutake of Specie Bank, Sejiro Furuya of the Furuya Company, and Captain Tozawa of Nippon Yusen’s (NYK Shipping) Katori-maru.

The “Times” also kept the region’s Japanese residents apprised of legislation that could endanger their community. In 1916, racist whites formed the Anti-Japanese League of Washington to agitate for exclusionary laws similar to earlier laws targeting Chinese. Modeled on a similar organization in California, it was among a coalition of groups that campaigned against land ownership by Japanese in Washington. Their actions culminated in the passage of the “Alien Land Law” (1921) barring renting or leasing of land to “aliens ineligible for citizenship.” In response, Seattle-area Nikkei formed the Japanese Progressive Citizens League to advocate for their rights and counter anti-Japanese propaganda. Throughout, the “Times” kept the region’s Japanese-speaking residents informed and helped make a coordinated response possible.

In 1918, Suginoo sold Arima his interest in the “Times” and returned to Japan. Arima’s youngest son Sumio arrived in the US that year to attend the New York Art Institute. After completing his studies, Sumio joined his father and brother at the “Times.” Under the Arimas’ leadership, the “Times” ran a series of articles highlighting individuals of interest to their readers. The column, “Ichinichi hitori hito iroiro” (One Person a Day – Let Us Introduce Them) featured notable people living and working in the Seattle area. While its focus was on the Japanese community, the Arimas also interviewed non-Japanese including Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson.

As a critical conduit of news from Japan, the “Times” sometimes became part of the story itself. In late 1923, it covered the devastating Great Kanto Earthquake (Tokyo) and its aftermath. In response, “Times” readers sent financial donations to the paper, which forwarded the funds to Japan. As news of the need for aid spread to the English language press, the “Times” joined with other Japanese news outlets in coordinating aid to Japan. The response from non-Japanese was so great that the “Times,” the “Great Northern Daily News,” the Japanese Association of North America and the Northwest Japanese American Association published a joint letter of gratitude in the “Seattle Times” expressing their gratitude on behalf of Japan and Seattle-area Nikkei whose families were affected.

Tragedy struck the “Times” staff in 1929 when a blizzard engulfed a party of four climbers on Mount Shuksan, east of Bellingham. K.Furuya, a sketch artist on assignment from the “Times’” Portland office, was with three-non-Japanese mountaineers attempting an ascent when the weather turned. Before they were found, Furuya and a Seattle librarian, Thelma Martin, lost their lives. After a rescue party brought out the survivors, the bodies of Furuya and Martin were recovered and Sumikiyo and Sumiyoshi Arima traveled to Bellingham to make arrangements for Furuya’s remains.

Throughout the 1920s, increasing nativist sentiments among many whites led to more oppressive laws targeting the Japanese community. In 1923, legislators amended Washington’s Alien Land Law to bar sale and lease of land to Japanese born as US citizens. In 1924, Federal Law disallowed further immigration by Japanese women. The “Times’” readers followed events closely as the paper reported on the community response. In 1929, a number of Japanese community organizations in the US consolidated, founding the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) which held its first national convention in Seattle in 1930.

As the US entered the Great Depression (1929-1939), Sumikiyo Arima returned to Japan, leaving eldest son Sumiyoshi as editor-in-chief of the “Times.” Japanese-owned businesses were no less vulnerable to the changing economic tide and even the venerable Furuya Company succumbed to the financial crisis. Despite the troubled economy, Seattle’s Nikkei population of over 8,000 was the largest it had been since immigration began. The “Times” continued to cover community events such as the first Bon Odori celebration in Seattle, hosted by the Seattle Betsuin Buddhist Temple in 1932.

During the Depression, Seattle’s Nikkei population began to decline, dropping to under 7,000 (about two percent of Seattle’s population) due to Issei returning to Japan, Nikkei migrating to other parts of the US, and decreasing numbers of new immigrant arrivals. By then, Seattle’s Japanese business ownership included 50 greenhouses, over 200 hotels, 56 apartment houses, 225 restaurants, 90 dry cleaners and 140 groceries. The community’s importance even allowed the “Times” to produce a Japanese language morning news and events broadcast on Seattle’s KVI radio in the late 1930s.

On the eve of the coming war, Seattle’s Nihonmachi was a relatively stable community and the “Times” employed upwards of 50 staff and correspondents. While increasing tensions in the Pacific between Japan and the US caused concern, Seattle’s Nikkei remained optimistic that better days were to come.

Edward Echtle is a public history consultant and preservation professional based in Tacoma, Washington. He specializes in immigration and labor history in the Pacific Northwest and has worked on projects for the Wing Luke Museum, Historylink, the City of Olympia, and Ron Chew of Chew Communications.

Edward Echtle is a public history consultant and preservation professional based in Tacoma, Washington. He specializes in immigration and labor history in the Pacific Northwest and has worked on projects for the Wing Luke Museum, Historylink, the City of Olympia, and Ron Chew of Chew Communications.