By David Yamaguchi The North American Post

In recent issues — in its news, calendar section, and ads — the NAP has described the occurrence of two major June 26 virtual community events, Japan Fair (Bellevue) and Minidoka Pilgrimage. The two together posted many hours of online content. Thus, a reasonable question to ask is what is the best of these materials that merits watching?

A strong contender for a “Best in Show” blue ribbon would be “Japanese American History, Not for Sale” (YouTube, Minidoka Pilgrimage channel, 1 hr., 46 min.) A well-narrated documentary approaching TV quality, it describes three recent public auctions at which incarceration camp artwork came up for sale, related national JA community responses, and what ultimately became of the artworks.

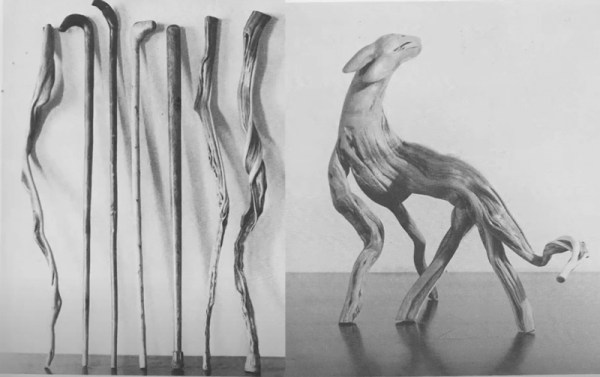

The first auction involved 450 items from the personal collection of author/scholar Allen H. Eaton. He used the artworks to write “Beauty Behind Barbed Wire” (1952), a seminal book on what has come to be known as “Gaman Art.” The author obtained the materials as donations from camp residents during visits he made to five of the camps, including Minidoka, in autumn 1945, as the camps were closing.

The uproar began when the artwork was posted for auction in the New York Times in March 2015. For JA readers immediately noticed the depravity of Eaton’s heirs making money from the donations. The dissenters likened it to selling artwork from Jewish concentration camps: profiting from distress. For the true value of the collection lies not in its total sales as separate pieces by “artist unknown,” but as art placed in context — by finding the artists, and displaying their work together with their individual life stories.

While seemingly impossible from an outsider’s perspective, in the JA community, some of the artists may still be alive and can be found through community networks. Others have adult children who can recognize their late parents’ art, and the like.

The insensitivity of public auctions of incarceration-camp art really hits home with a second announced sale involving two JA family bibles (2017). They were of art-interest because the owner had illustrated their margins with sketches. Yet on their blank pages he had also recorded the births and deaths of family members — which made them books that any family would treasure long into the future. Did the sellers not recognize this?

A third eBay auction (2021) involved sketches signed by a Nisei, whose daughter appears in the video.

What makes the video is its insightful narration by Nancy Ukai, Project Director at 50objects.org.

There is more to it, but this much should be sufficient to pique the reader’s interest to view it firsthand. In closing, local host Bif Brigman advises viewers who have camp art they want help finding a home for to “keep in touch” with Minidoka Pilgrimage; it is developing a list of suitable donation venues. For example, the Eaton collection ended up at the JANM.