By Chuck Tasaka

BAINBRIDGE ISLAND: OUR FIRST STOP

I have always been intrigued by and curious about the Japanese American internment history for years and have watched Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) programs religiously to learn about the wartime incarceration experience. Since there are many documentaries about Japanese Americans, and only a few films on the Japanese Canadian internment experiences on the local Knowledge Network, I know more about the Japanese American history.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) history had a huge impact on me. I admire their courage and the sacrifices they made to earn the respect of fellow Americans. The soldiers of the 442nd RCT were awarded close to 9500 Purple Hearts, 21 Medals of Honor, and 7 Congressional Medals, which enabled them to be the most highly decorated regiment of its size. They were my heroes even though I’m Canadian. I watched the movie Go for Broke way back in 1951 and I will never forget the time actor Van Johnson hollered the word ‘bakatare,’ or ‘stupid’ in Japanese when he forgot a 442nd’s password. There was a roar of laughter from the packed theatre in Greenwood. In Waikiki, I went to Fort DeRussy Museum and bought so many 442nd RCT memorabilia that the shopkeeper added the 522nd pin and a book free of charge.

Another documentary that really affected me emotionally was the story of how Bainbridge Island, Washington newspaper publishers Walt and Millie Woodward supported the local Nikkei right from the start of WWII, even at the expense of many subscribers cancelling their paper. It was the first time that I had learned that some Caucasians sympathized and backed the Nikkei.

I watched the movie Farewell to Manzanar many years ago and more recently, saw the documentary film, The Manzanar Fishing Club, both focusing on the Japanese American concentration camp, Manzanar, which is located in California. Therefore, it took years before I realized that there were nine other Japanese American concentration camps. I knew very little about Gila River (Arizona), Poston (Arizona), Rowher (Arkansas), Jerome (Arkansas), Topaz (Utah), Amache (Colorado), Tule Lake (California), Minidoka (Idaho), and Heart Mountain (Wyoming).

It wasn’t until I started following the Discover Nikkei website, which is hosted by the JANM (Japanese American National Museum) that I began to learn more. I didn’t know that this website existed until Yoko Nishimura, editor of Discover Nikkei, contacted me regarding republishing my article “Greenwood: First Internment Site,” which was first printed in the JCCA (Japanese Canadian Citizens Association) Bulletin magazine. From then on, I started to take a passionate interest regarding Nikkei existence in other parts of the world. I had enough material to research all ten of the US camp sites. I found out that JAs generally use the term ‘concentration camp’ in written materials, whereas Japanese Canadians refer to a more euphemistic term ‘internment camp.’

Reading stories on Discover Nikkei piqued my interest to compare the differences and similarities of both countries’ Nikkei wartime experiences. For many years, my brother Stephen was interested in Nikkei experiences. He asked me to make out an itinerary to take a trip to Manzanar. That was two years ago. For one reason or another, the trip was postponed. First, I was working on upgrading the Nikkei Legacy Park in Greenwood and then Stephen and his wife Dianne moved back to Vancouver and were busy settling in.

After a trip to China last October, the three of us checked our schedules and found out that we were all free in April 2018. By that time, Stephen and Dianne’s curling season would have ended. Then, our childhood friend Tony wanted to tag along, even though he was only mildly interested in the Japanese American internment history. Therefore, I set the date for April 24 so that we could attend the Manzanar Pilgrimage on the 28th.

We left Vancouver, B.C. when the weather was still iffy. Snow was falling at higher elevations and rain kept the temperature cool. Our first planned stop was at Silver Reef in Bellingham for breakfast. However, instead of eating in the cafeteria, we decided to order our breakfast ‘on the go’, eat inside the van, while driving to Seattle. It was sunny and warm. By luck, we were able to catch the 10:40 am ferry instead of the planned 11:20 am to Bainbridge Island. At this moment, I said to myself, “What luck!” I pointed upwards and thanked my parents. I knew they are watching over us.

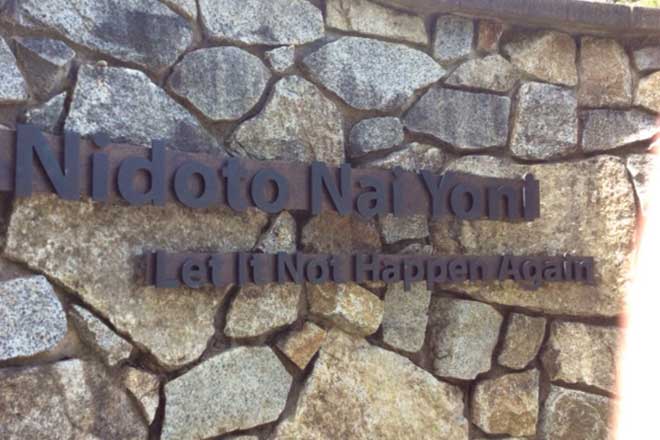

Bainbridge Island (B.I.) wasn’t one of the U.S. internment camps, but the Nikkei who lived there were the first group of Japanese Americans to be forcibly removed from their homes on March 30, 1942. I had read about the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial, ‘Nidoto Nai Yoni – Let It Not Happen Again’ and our primary reason was to visit the memorial; but first we made a stop at the Bainbridge Island Historical Museum because it’s a 15-minute drive to the park from the museum.

We found the B.I. Historical Museum quite easily as it is located near the ferry terminal. Before the four of us even opened the front door, we knew that this museum focused on local Nikkei islanders. We were greeted with friendly smiles, and I asked if Katy Curtis, the Museum’s Education Outreach Coordinator, was present. We had arranged with Katy to meet Frances Kitamoto-Ikegami, the last surviving internee on B.I. Katy informed us that Frances wouldn’t be coming in until 1:00 pm. That allowed us to leisurely view the wonderful main exhibition. This is a small community, so Katy phoned Kay Sakai-Nakao, another Nikkei local, to come to meet the Canadian Nikkei tourists.

Since we had arrived to the Island earlier than expected, and both Frances and Kay were expected at the Historical Museum later, we were able to drive to the memorial park on Eagle Harbor Drive. The memorial’s red cedar walls with curvy lines caught our attention immediately. The names of the families who were incarcerated were on the base of the walls. I have a similar project going on at the Nikkei Legacy Park in Greenwood with family plaques to be put on the wall. So far, I have about 65 families who have purchased plaques. The only difference is that B.I. plaques have the age of each Japanese American Islander (there are 227) at the time of the relocation in 1942.

The beauty of the wall is that there are artistic renderings of the lives of the eight Nikkei pioneers. The carved portraits show how they reacted to the Executive Order 9066. It was almost like haiku. A sentence or two gave profound emotional and heartfelt feelings of uncertainty by a farmer, baseball player, housewife, and student. The portrait about a baseball player, Paul Ohtaki, included his words: “Just a week before we were to leave, coach ‘Pop’ Miller put in all six Japanese Americans. Despite errors and not hitting, he let us play the whole game. We lost 15-2.” Through this profile, we learned that Paul also kept in touch with the Woodward family to update them on the daily going-ons at camp during the war. A visitor centre at the memorial is planned in the future. In all, 227 Nikkei were forcibly removed on March 30th, 1942.

Another carving had a mother and child, and it read, “We were really careful, we were prisoners and they had guns with spears.” – Fumiko Nishinaka Hayashida.

We headed back to the Historical Museum to meet the two local ladies. At first, we were planning to meet the last surviving internee Frances who was volunteering that day, but we received a bonus when 99-year old Kay showed up. She was shoveling dirt that morning! Thanks to Katy, we were able to meet and chat with the last two surviving internees living on the island. We heard their stories and I pointed out the differences of the two countries’ intent to remove the Nikkei off the west coast.

Kay and Frances told us that they were sent to Manzanar, California initially, but later their families asked to be transferred to Minidoka, Idaho. Kay remembers the hot, dusty summer and very cold winter in Manzanar. Her family’s barracks was located near the administrative building where 11 men were shot when a riot between military soldiers and an angry crowd of Japanese American inmates broke out. Two died in that mayhem. It must have been a scary moment for a young lady of 22 to witness.

Frances explained that when they left the farm in Bainbridge Island to a Filipino friend, it was well-taken care of when they returned after the war. During their time in Minidoka, Frances’ mother wished that she had her washing machine. Guess what? Their Filipino friend drove all the way to the camp in Idaho to deliver it! Therefore, the Kitamoto family was one of the lucky ones. Frances later married and went with her husband to Florida where he was an engineer. In 1960, she returned to teach on Bainbridge Island.

At the memorial, there is another family featured on the wall that includes a quotation by Noburo Koura stated, “We put the farm under Mr. Raber’s name while we were gone. When we came back, he returned it to us.”

Kay also returned to Bainbridge Island after the war, where her family had a large plot of land. I later found out that there is a school named in honour of her father Sonoji called Sakai Intermediate School. When we took the wrong road after visiting the park, we saw a road sign with Sakai on it. I guess Kay was too modest to let us know.

Bainbridge Island reminded me of Mayne Island, B.C. (Gulf Islands) in a way. When the War Measures Act went into action in March 1942, all the islanders were sent to Hastings Park Exhibition holding grounds. In both communities, Caucasian friends and neighbours walked along the dock to bid a tearful farewell. The only difference is that there wasn’t a military guard with a rifle and bayonet on Mayne Island. Why would you need a rifle to escort a sweet 5-year old Frances to the docks? I also noticed how well-dressed everyone was while walking down to take the ferry. They all looked like they were going to church on a Sunday. Apparently, they wore their best clothes as human luggage so that they could take many more essentials in their suitcases.

Japanese Canadians lost everything when the government auctioned off all of their boats, houses, and treasured items such as Ohina doll set, piano, radio, and fine china. It wasn’t until 1949 that the Japanese Canadians were given the freedom to return to the west coast. In Bainbridge Island, many Japanese Americans had the support of Walt and Millie Woodward, and friends to take care of their properties and belongings. There was some initial opposition to their return to the Island, but eventually over several years, life was restored to pre-war days.

What a thrill it was to actually carry on a meaningful person-to-person conversation with Kay and Frances. It wasn’t just viewing the artifacts and displays in a museum. We received a personal guided tour. What wonderful volunteers and staff they have there.

To be continued…

About the author: Chuck Tasaka is the grandson of Isaburo and Yorie Tasaka. Chuck’s father was 4th in a family of 19. He was born in Midway, B.C., and grew up in Greenwood, B.C. until he graduated from high school. Chuck attended University of B.C. and graduated in 1968. After retirement in 2002, he became interested in Nikkei history. (This photo was taken by Andrew Tripp of the Boundary Creek Times in Greenwood.)

[Editor’s Note] This article was originally published in Discover Nikkei at <www.discovernikkei.org>, which is managed by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.