By David Yamaguchi

The North American Post

On Sept. 24, I was pleased to be invited to attend the 20th anniversary gala of Densho, the Seattle-based nonprofit dedicated to capturing and sharing the World War II incarceration stories of Japanese Americans on the web.

As it had been some years since I last attended a Densho event, I felt a bit of culture shock. For the well-dressed attendees pretty much included the movers and shakers of greater Seattle Nikkei society. There were politicians, business owners, heads of nonprofits…

Fashion and glitter aside, however, the event provided a meaningful opportunity to reflect on Densho’s accomplishments to date. As editor Shihou Sasaki provided an overview and highlights of the evening in last week’s issue, I will not repeat that content here. Instead, I will consider Densho’s gifts to our own community, and touch on their significance to the world beyond.

FOR NISEI in the twilights of their lives, I believe Densho has helped them through validating their life stories. A generation whose median age was 18 at the time of Pearl Harbor, they had learned to live their lives by “not making waves” owing to decades of pre-war, wartime, and post-war prejudice. This pattern of not calling attention to themselves was so widespread that author Bill Hosokawa subtitled them “The Quiet Americans” in his seminal 1969 volume on the generation. While the Nisei knew they had done nothing wrong before and during World War II other than to have Japanese faces, it must have been an entirely new experience for them to field calls from Sansei—people like their own adult children but not them—asking them to sit before video cameras in their living rooms to tell their stories for the world. Like the Redress Hearings magnified many-fold, which few had an opportunity to participate in or witness, it was a chance for the many to set the story straight. In the process, they freed themselves psychologically of an incarceration stigma that yet lingers in American society: that if they were imprisoned, then they must have done something wrong.

FOR SANSEI, Densho has captured the story of our parents in an encompassing way that we could not as individuals. In doing so, it has helped foster family conversations through reducing the knowledge gap about World War II between the two generations. In short, it has enriched our lives.

FOR YONSEI and later generations, Densho has provided the gift of the past in an Internet format familiar to them. All people, at some point in their lives, ponder the lives of their ancestors: how they lived and the struggles they faced. Few other peoples have access to such an archive.

FOR THE WORLD, the main thing that Densho has done is put human faces on JAs, and on the Nisei generation especially. To hear Nisei speak on video makes it clear at once that they are Americans. While many flip into Japanese now and then, to quote their Issei parents, their English is colloquial, fluid, and native. They were not “the enemy.”

In Seattle, we think that everyone knows about JAs. In fact, we comprise only a small branch on the human family tree. Accordingly, one of the most common questions I fielded throughout my youthful forestry travels across the United States during the 1970s to 1990s was, “Why is your English so good?”

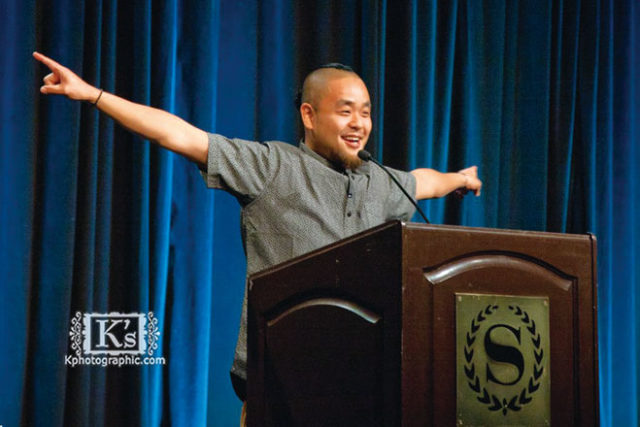

This is why the video format of the Densho oral histories makes a difference. As emphasized by banquet keynote speaker Dale Minami, the attorney for the rehearing of the landmark Fred Korematsu case, you have to touch people’s hearts before you can move their minds.

An example is helpful to see what Mr. Minami means. These days, major national newspapers use video to support their text articles. One such story at some distance from that of West Coast JAs is that of Japanese war brides, 45,000 of whom settled widely across the United States following the occupation of Japan. A Sept. 22 Washington Post article by hapa-daughter journalist Kathryn Tolbert sketches their experiences. While her words carry the story, it is the accompanying video clip of mothers and children, in the 1960s and present-day, that makes one like the protagonists, and want to learn more about them.

OF INTEREST FROM NOW will be watching how Densho broadens its content to include the stories of Native Americans, Muslim Americans, and other disadvantaged groups. This will help to connect the JA interviews with those of others. It will help dispel the notion in some viewers’ minds of, “Why should I bother to learn JA history?” For as readers of this paper know, JA history is American history in a nutshell.

Who is an American? What rights and responsibilities come with that status? Moreover, American or not, how should people with different backgrounds treat each other on the street? I look forward to seeing how Densho approaches these questions.