By Sergio Hernández Galindo

Translated by Kora McNaughton

For The North American Post

In 1912, the mayor of Tokyo, Yukio Ozaki, presented the United States with almost 3,000 cherry trees, which were then planted throughout the U.S. capital. In the years that followed, Washington D.C. came to be covered with millions of cherry blossoms, coloring the city’s landscape every year in early spring.

There was also an effort to plant thousands of cherry trees in Mexico City. During his presidency, Pascual Ortíz Rubio (1930-1932) asked the Japanese government to donate cherry trees to be planted along the city’s principal avenues as a symbol of the friendship between the two countries. Japan’s foreign minister asked Tatsugoro Matsumoto, an emigrant who had been living in Mexico for many years, for advice on the feasibility of cherry trees adapting to the city’s natural conditions. Matsumoto explained to both governments that cherry trees were unlikely to bloom there because they require a much more abrupt change in temperature from winter to spring than occurs in Mexico City. Following Matsumoto’s recommendation, the idea was discarded.

Tatsugoro Matsumoto was one of the first Japanese emigrants to Mexico, arriving just one year before the first large-scale emigration of Japanese pioneers to Chiapas in 1897.

Actually, Matsumoto was one of the first immigrants to Latin America since he had worked in Peru years before coming to Mexico. He’d been invited to Peru by Oscar Heeren, who wanted to create a Japanese garden in one of the best-known places in Lima: the Quinta Heeren. There, Matsumoto met a wealthy Mexican rancher and mine owner, José Landero y Coss, who was impressed by Matsumoto’s work. Landero invited Matsumoto to his ranch at San Juan Hueyapan, near the city of Pachuca, to create a similar garden with an artificial lake.

After creating the garden at Landero’s ranch, Matsumoto returned to Japan to visit his wife, but he had already decided to settle permanently in Mexico. Before returning he stayed for a short time in the United States where he maintained the large Japanese garden built in Golden Gate Park as part of the 1894 World’s Fair in San Francisco. When he arrived in Mexico in 1896, Matsumoto didn’t know that he would never again return to Japan and would instead live in Mexico until his death in 1955 at the age of 94.

At the time Matsumoto came to Mexico, the city’s Roma neighborhood was one of the most elegant, where the new rich who rose in prominence during the government of Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911) preferred to build their homes. These mansions had large gardens that required a caretaker. Matsumoto, undoubtedly, was the ideal person to design and care for the gardens of fashionable residences throughout the neighborhood: He was more of a landscape architect than a gardener, having graduated as an ueki-shi in Japan. This activity had enjoyed great prestige since the Muromachi era (1336-1573) when these professions flourished as a result of greater interest in gardens, floral arranging and tea ceremony. Later, during the Tokugawa era (1603-1868), the growth of cities and the rise of certain sectors of society focused on leisure and pleasure (ukiyo, or floating world) earned these professions broad recognition.

Thanks to his hard work and the beauty of his gardens, Tatsugoro Matsumoto began to create a name for himself among the Porfirian elite. In 1900, the English-language newspaper Mexican Herald (*) noted the work of this Japanese immigrant and his fame reached the ears of Porfirio Díaz and his wife, Doña Carmelita. The president placed Matsumoto in charge of all floral arrangements at the presidential residence inside Chapultepec Castle, as well as the forest surrounding that majestic edifice.

In 1910, two significant achievements marked the life of Matsumoto. In September of that year, Mexico celebrated the first centenary of its independence. For such an important commemoration, President Díaz invited representatives from governments friendly to Mexico. Japan sent a high-level delegation led by Baron Yasuya Uchida and his wife. The Japanese legation in Mexico sponsored a major exposition of Japanese products at the Crystal Palace (now known as the Chopo Museum) where to one side Matsumoto created a garden with a small artificial lake. The garden was inaugurated by President Díaz himself as well as the Japanese diplomatic delegation.

That same year, Sanshiro Matsumoto, Tatsugoro’s son, arrived from Japan in search of his father, with whom he had lost touch. Sanshiro organized the administrative part of the business, which his father had neglected. The two of them then began to develop a large emporium, despite the enormous difficulties they faced at the start of the revolutionary movement in Mexico.

After the armed confrontation had subsided and the political situation was once again stable, the Matsumotos recommended to President Álvaro Obregón (1920-1924) that jacaranda trees be planted along the city’s main avenues. Tatsugoro Matsumoto had introduced jacarandas from Brazil and reproduced them in his greenhouse. The climate was appropriate for the tree to blossom in early spring and, according to Matsumoto, the flower would last longer because of the lack of rain in Mexico City during that season.

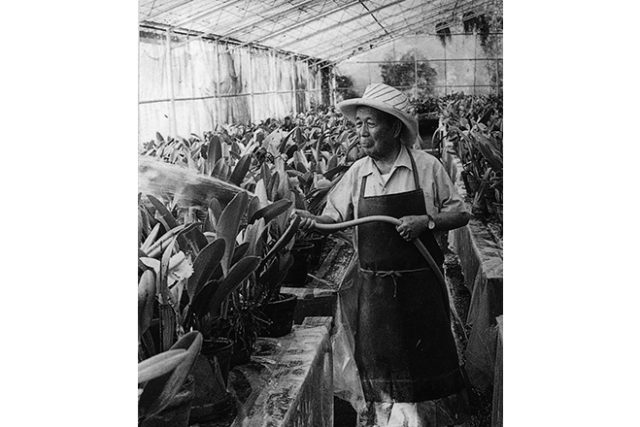

In the following years, the Matsumotos bought a home in the Roma neighborhood and installed a greenhouse to reproduce the plants and trees they grew with great care. In 1922, Maso Matsui arrived in Mexico to marry Sanshiro; she and her mother-in-law later opened a flower shop at the front of their house. There, they sold flower arrangements for parties and ceremonies of all kinds, including weddings. Over the following decades, it became the leading shop of its kind, where the city’s elite came for one-of-a-kind flower arrangements.

The Matsumotos maintained close relationships with Mexico’s presidents and other important politicians, who proved to be of great help during the years in which Japanese communities from throughout the continent were persecuted by the United States as a consequence of the war with Japan. Tatsugoro and Sanshiro became leaders of the Japanese community and served as representatives before the Mexican authorities when the government ordered people of Japanese descent from Mexico City and Guadalajara to be interned in concentration camps in 1942.

Tatsugoro was one of the leaders of the Mutual Assistance Committee known as Kyoei-kai, an organization created by immigrants to help those Japanese people who arrived in the first few months of that year from other places to be interned in camps. The Kyoei-kai opened an office in the San Cosme neighborhood, where arriving families were given temporary shelter. But there were so many people that the Matsumotos installed a shelter to house more than 900 immigrants at El Batán, their 200-hectare ranch, located south of Mexico City where the Unidad Independencia complex sits today.

Later, Sanshiro, Luis Tsuji and Alberto Yoshida looked for a place where the internees could be housed and grow their own food. They bought a ranch near Cuernavaca known as Hacienda de Temixco, where the neediest families lived during the war, harvesting rice and vegetables. Sanshiro, who had become a Mexican citizen, was able to buy the ranch despite the confiscation of property and bank accounts belonging to Japanese citizens.

During those difficult times, jacaranda trees were planted throughout Mexico City and elsewhere in Mexico, such that today it is considered a native tree. Tatsugoro’s advice was both correct and visionary, and today we enjoy our hanami (flower viewing festival) with the jacarandas that magically appear every March and April, reminding us that the Matsumoto legacy continues on.

Notes:

* The Mexican Herald, November 4, 1900.

[Editor’s Note]

This article was originally published in Discover Nikkei at www.discovernikkei.org managed by the Japanese American National Museum. Sergio Hernández Galindo is a graduate of Colegio de México majoring in Japanese studies. He has published numerous articles and books about Japanese emigration to Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America. He has taught classes and led conferences on this topic at universities in Italy, Chile, Peru and Argentina as well as Japan. He was part of the group of foreign specialists in the Kanagawa Prefecture and a fellow of the Japan Foundation, affiliated with Yokohama National University. He is currently a professor and researcher with the Historical Studies Unit of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History.