History of Seattle Nikkei Immigrants from ‘The North American Times’

This series explores the history of the pre-war Japanese community in Seattle, by reviewing articles in “The North American Times,” which have been digitally archived by the University of Washington and Hokubei Hochi Foundation (hokubeihochi.org/digital-archive). Publication of this series is a joint project with discovernikkei.org.

By Ikuo Shinmasu

Translation by Mina Otsuka

For The North American Post

‘The North American Times’ was first printed on September 1, 1902, by publisher Kiyoshi Kumamoto from Kagoshima, Kyushu. At its peak, it had a daily circulation of about 9,000 copies, with correspondents in Spokane, Vancouver BC, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Tokyo. When World War II started, Sumio Arima, the publisher at the time, was arrested by the FBI. The paper was discontinued on March 14, 1942, when the incarceration of Japanese American families began. After the war, the paper was revived as “The North American Post.”

Part 5, The Great Seattle Shipping Route

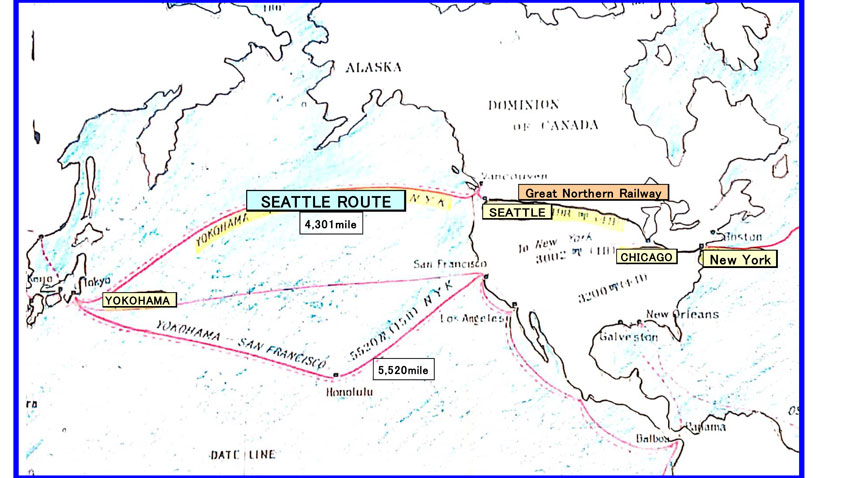

In the last part, I introduced articles about some notable Issei in Seattle in 1919 and local peoples’ expectations for the Japanese Consulate. In this part, I would like to focus on the Seattle Route which accelerated Seattle’s development and helped the Japanese residents travel back and forth to Japan.

Opening of the Seattle Route

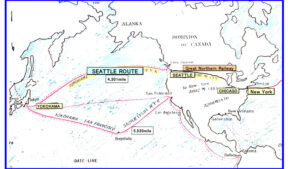

Nippon Yusen Kaisha’s (NYK Shipping’s) Seattle Route opened in 1896, connecting Seattle and Yokohama. The opening of the route triggered a rapid increase in the number of Nikkei immigrants to Seattle.

“City of Seattle and NYK” (The North American Times, Jan. 1, 1920)

Seiichi Nakase, who was vice president of the Seattle sub-branch of Nippon Yusen, commented on the opening of the Seattle Route, looking back on the old days.

“About 20 years ago, when railroad king James J. Hill was extending the Great Northern Railway to Seattle, he received a piece of advice from an influential Chicago entrepreneur, James Bray Griffith: ‘We will need to work in partnership with Japanese marine transportation businesses in the future.’ It was then decided that Mr. Hill would go to Japan to look into that possibility. At the time, Yusen Kaisha was deciding its route to the U.S. With Mr. Hill’s input and the possibility of future US-Japan trading business, Seattle was chosen. In 1896, Miike-maru, a ship that weighed no more than 3,000 tons, opened up the route for the first time.”

The opening of the Seattle Shipping Route connected Seattle to the transcontinental railroad system, which boosted the development of Seattle.

The Seattle Route and Great Northern Railroad

Six ships are recorded to have traveled the Seattle Route around 1918: Fushimi-maru, Suwa-maru, Katori-maru, Kahima-maru, Atsuta-maru and Kamo-maru. These ships regularly traveled between Seattle and Yokohama about every three weeks.

In January 1918, a series of articles describe how Aimaro Sato (Japanese ambassador to the U.S., 1916-1918) traveled from New York on the Great Northern railroad, boarded Fushimi-maru in Seattle and returned home.

“Ambassador Sato Trapped in Snow” (North American Times, Jan. 14)

“The train that carried Ambassador Sato on the Milwaukee Line in Chicago was forced to halt near the state of Ohio, due to snowfall. The train has been already delayed for 20 hours now… According to the incoming telegram from the Chicago sub-branch of Nippon Yusen, Ambassador Sato left Chicago on the evening of the 14th and was expected to arrive in Seattle on the night of the 17th assuming there would be no mechanical trouble on the train. For the past few days, however, there has been a blizzard east of the Rockies. Since no train can move west at the moment, we cannot expect the regular arrival of any train. In any case, (Sato) will not make the scheduled sailing of Fushimi-maru on the 17th, yet we have not heard about it being postponed to the 19th.”

“Ambassador Sato Passing Through” (From the Spokane Branch, Jan. 18)

“Ambassador Sato’s train got to Spokane at 5 p.m. on the 17th, arriving behind schedule. After a brief stop, the train left for Seattle late in the night. As none of the (Spokane) Japanese residents knew of the ambassador’s arrival, Mr. Sato stayed inside the train until 8 p.m.”

“Ambassador Sato’s Long-Awaited Arrival” (Jan. 18)

“The train carrying Ambassador Sato reached Seattle at 9 a.m. on the 18th, a few hours behind schedule. Consul Matsunaga, Secretary Takeuchi, two chairpersons of Nihonjin-kai (Japanese Association) Takahashi and Okuda, Nakase (NYK), a secretary from Nakamura Jitsugyo (Business) Club, Suzuki from Tohokujin-kai (Northern Honshu Assn.) and Secretary Nakajima (Nihonjin-kai) welcomed him at the station. Ambassador Sato slowly got off the train with his attendants.

He shook hands with everyone and expressed his gratitude, saying “Thank you for coming to meet me.”

He finally seemed to feel at ease.

“As our train got delayed, I learned the lesson that we can’t rely on the schedule.”

He then was led to Hotel Washington.

This good-natured gentleman willingly told me (the reporter) about his experience, as I bothered him at the hotel while he was resting.

“I’ve never had such an insane experience like this. We were already late by 48 hours en route. Since I heard that the sailing of Fushimi-maru was moved up to the 17th, I was so anxious but there was nothing I could do about it in the snow. They made sure that the train was constantly heated, so I was able to survive the cold. Also, everyone was so good to me.”

“The (Afternoon) Banquet” (Jan. 18)

“At noon on the 18th, a banquet was hosted by Consul Matsunaga at Washington Hotel. With Ambassador Sato as a guest of honor, Takahashi, Okuda, Ishida and Nakase represented the Japanese (community) side, and on the Caucasian side were the heads of the Chamber of Commerce, Mr. Rose and Mr. Roman, and 23 other well-known people… From 6:30 p.m., Ambassador Sato attended a dinner party hosted by the Jitsugyo Club and spent time with many fellow Japanese residents.”

Like Ambassador Sato, prominent figures from Japan at the time frequently visited Seattle. Japanese residents held a welcome party with great hospitality each time such a figure arrived.

“Fushimi-maru Leaves Seattle” (Jan. 19)

“Fushimi-maru left for Japan on the afternoon of the 19th, later than the scheduled time of 2 p.m. Ambassador Sato took his attendants and boarded a little after 9 (a.m.). The security was heightened at the wharf as usual where they prohibited any entry other than passengers, and Consul Matsunaga was the only one who was allowed to board. Ambassador Sato left a message of gratitude with the Consul that he was truly grateful for the warm welcome by the Japanese residents in Seattle. There were about 30 passengers in the first-class cabin, and the total number of passengers from the second and third-class cabins was 200-plus. Heiji Okuda, members of his jitsugyo group of home-country observers, Tamotsu Nakatani — the chief manager of Ban Shoten (store) in Portland — and others were present too.”

If Ambassador Sato had missed the Fushimi-maru, he would have had to wait until February 7 for the Kashima-maru.

The Shortest Ocean Route

“Japan-US Ocean Route and European Ocean Route” (Mar. 8, 1919)

“In Japan, traveling to Europe and/or the U.S. has become a craze after the (World War I) cease-fire, whether it’s for business or pleasure… There are two routes connecting Yokohama to Paris, namely the Seattle Route and the European Ocean Route (Yokohama – Indian Ocean – Paris). If one takes the Seattle Route and travels first-class by the (Great Northern Seattle to Chicago) railroad to reach Paris, it will cost 927 yen (about 900,000 yen at the current rate), including all meals and accommodation charges. If one books second-class, the total will be 582 yen (about 600,000 yen at the current rate). If one takes the European Ocean Route to Paris, on the other hand, the first-class trip will be 710 yen in total, and the second-class trip will be 490 yen. It will take 27 days if one takes the Seattle Route… and 52 days if one takes European Ocean Route.”

“City of Seattle and NYK Shipping” (Jan. 1, 1920)

Seiichi Nakase, the vice chief at the then Seattle sub-branch of NYK Shipping, explains how the Seattle office became a branch.

“Since the opening of the Seattle Route in 1896, NYK has outsourced all its work in Seattle to the Great Northern Railway. As Seattle kept growing as a trading port, however, it opened a sub-branch office (there) in 1911 and the first manager was Mr. Studley of the Great Northern Railway. The sub-branch office in Seattle, a city that continued to grow, was promoted to a branch office at the general meeting held in November 1919, following the same changes in New York and Singapore. When they decided to assign a Japanese person to the manager post, Mizutaro Watanabe, who was vice president at the Yokohama branch, got the offer. At the same time, I became vice president at the branch in New York.”

Future World Ocean Route: “The Japan-US Route on the Pacific Ocean” (Jan. 17, 1920)

The following article similarly notes that Seattle Route is the shortest international ocean route.

“A reporter from The North American Times visited the Yokohama branch and conducted an interview… Watanabe mentioned that Seattle Route is about 1,000 miles shorter than Southern Ocean Route (Yokohama – San Francisco). The Great Northern railroad route is also shorter than San Francisco to Chicago (by transcontinental railroad through Utah). It’s the most convenient route for international travelers.”

The Star Ships Hie-maru and Hikawa-maru

After 1930, Hie-maru, Hikawa-maru and Heian-maru became the three major ships to travel the Seattle Route.

“Captain Takahashi’s Celebratory 100th Traversing of the Pacific Ocean” (Nov. 30, 1934)

“Captain Takahashi’s navigation of Hie-maru this time marked his 100th traversing of the Pacific Ocean. This follows Captain Yamaguchi’s 100th traverse celebration the other day. Captain Takahashi held a private celebration at home. It is easy to say that he has crossed the ocean 100 times. However, the fact that it usually takes two weeks to cross the ocean these days makes the frequency of his (round-trip) journeys total seven times a year. He is immersed in the deep blueness of the sky and the ocean day after day, spending 21 days at home out of the whole year. His record is simply admirable.

‘You have to be thick-skinned like me if you want to be a sailor. I’ve been a bit absent-minded since I was young, so I guess that worked out for the better,’ said the captain, showing his humbleness… As for my record on the Pacific Ocean, I would say that it has become my home ever since I crossed it on a training ship in 1909. Starting with my very first journey on Kitano-maru after I graduated from Tokyo Shosen (Gakko, Tokyo Merchant Shipping School) in 1910, I’ve been traveling back and forth on Aki-maru, Kaga-maru, and Mishima-maru. I’ve never counted my trips before, but it turns out that this is my 100th… I’ve done it 26 times on just the Hie-maru alone. Being the kind of ocean that it is, which usually gets rough and stormy, I have no (specific) memories or adventures to recall on the North Pacific Ocean.”

“Hikawa-maru to Arrive in Port Tomorrow Morning through Rough Weather on the Pacific Ocean” (Dec. 26, 1934)

“NYK’s Hikawa-maru is expected to arrive in port tomorrow morning, yet the weather on the Pacific Ocean has been rough for the past few days. The radio contact we received around the 20th reported a severe storm on the ocean and the English ship Penrose(?) was wrecked, with its control destroyed 1,700 miles from Seattle. A lifeboat is seemingly unable to move due to the waves and the safety of 40 crew members is at stake.

Expected to arrive in port tomorrow on the 27th, the Hikawa-maru kept running adeptly outside the storm area, but the ship is said to have passed Victoria this morning, heading straight to its last wharf directly through the storm yesterday evening. Yet arriving in port tomorrow will reportedly be no problem. Hikawa-maru will be the last ship from Japan to arrive this year.”

“NYK’s Hikawa-maru Arrives in Port in Seattle This Morning” (Dec. 27)

“As the last ship to Seattle this year, NYK’s Hikawa-maru arrived in port this morning. Fumitaro Kaneko was the captain. Passengers were as follows: First-class (passenger names), second-class…, third-class….”

On the bottom of the same page in the same issue was a note titled “Personages Arriving” as follows:

“On Hikawa-maru which arrived in port this morning were Yoshinori Otsuka (Oji Paper Co.), Hisae Takahara (Lieutenant Commander of Kure, a city near Hiroshima), Yuji Yamada (Mitsui & Co., Ltd.) and others.”

The North American Times reported the name of every single passenger each time a ship from Japan arrived in Seattle.

Heian-maru

My father Atae was a Nisei who was born in Seattle in 1914, but he returned to Japan in 1929 when his father Yoemon passed away. In 1936, he revisited Seattle and returned to Japan in 1941, taking the Heian-maru both ways. This is how he described his experience.

“On every two-week trip by ship, we spent at least one day on an extreme rough sea and the ship shook hard. We faced waves as high as 10 meters trying to wreck our ship, but we managed to dodge side waves and navigate through the waves. Our ship could have overturned if directly hit by the side waves. Because of the huge sway, almost everyone got seasick and couldn’t get out of bed. I was fine, and when I went to the dining room at dinner time, which was always full of passengers, I saw no one.”

Hie-maru, Hikawa-maru and Heian-maru, the ships that sailed the Seattle Route, were of extreme high quality that ensured safe passage through rough waves in severe storms. Supporting the development of Seattle, the Seattle Route was invaluable to the Nikkei people, connecting Seattle to their dear homeland of Japan.

In the next part, I will introduce articles about the growth of barbershop businesses owned by Japanese residents in Seattle.

References

Kaigai Ryoko Annai-sha (Foreign travel guide), “Travel Guide to the U.S.,” 1927.

Kojiro Takeuchi, “History of Japanese Immigrants in the Northwestern United States,” Taihoku Nippo-sha, 1929.

Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha, editors. “50 Years History of Nippon Yusen,” 1935.

Editor’s note. The clockwise sailing route followed the North Pacific Gyre, which causes the main ocean currents to flow clockwise, in response to the eastward rotation of Earth.