By David Yamaguchi The North American Post

From the start of this review, I will state that “Bridge to the Sun,” a new World War II Japanese American Military Intelligence Service (MIS) book, is due out this fall by “New York Times” bestselling author Bruce Anderson (“Sons and Soldiers,” 2017, Morrow). However, as “Bridge” won’t go on sale until September 27, curious readers might want to bring themselves up to speed in the meantime. In doing so, they will find that “Nisei Linguists” by James McNaughton is the only widely available reference on this topic. This deficiency is a great disservice to the exceptional MIS men who served. Nonetheless, McNaughton is a great read.

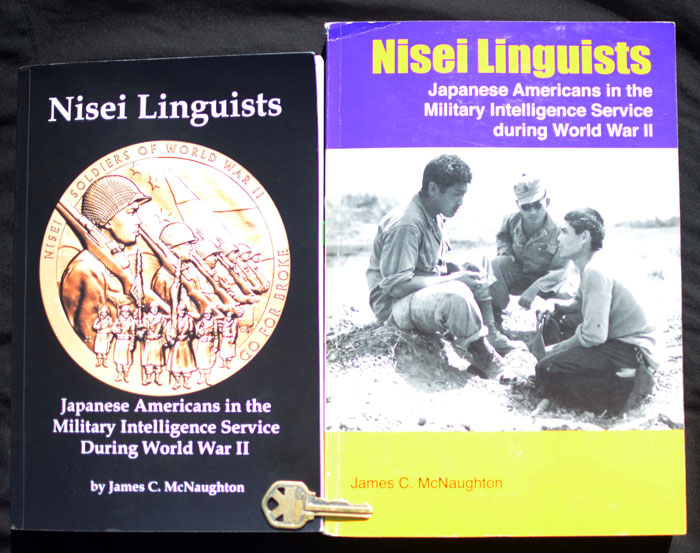

Before purchasing McNaughton, it is important to know that there are two editions. The black abridged version is sold on Amazon, but can be disappointing as it lacks figures, references and an index. Without the latter two, one cannot know where the author obtained his information nor easily refer back to topics previously mentioned. By contrast, the unabridged version is more comprehensive and impressive, in part owing to its glossy paper throughout, which is usually reserved for photo inserts. Its deficiency is that it is too heavy to read comfortably. It hefts similarly to “Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary.” Its paper also makes the volume “too good” to mark up with a highlighter, which students (and book reviewers) like to do. As I ended up with both editions, I find that I read them in tandem, the smaller version owing to its more comfortable weight and highlighter-inviting paper, and the heavy one as a desk reference for its photos, maps, and tables. For most readers, the slimmer volume would suffice.

Turning to McNaughton’s content, I found it immediately fascinating, to the extent that individual chapter reviews are merited. Accordingly, this review covers only Chapter 1 because in only 20 pages, it becomes obvious that the US Army military historian has much to share. While all interested in JA history would find it useful, former students of Japanese language schools will especially relate to the chapter’s findings. The reason is that it concisely describes why so few Nisei linguists were available to the US Army when they began looking for them on the West Coast in mid-1941.

Think about it. If over 112,000 West Coast Nikkei entered the internment camps in early 1942, of whom two-thirds were Nisei, one would expect there to have been 74,667 bilingual Nisei, for their parents came from Japan and spoke Japanese at home! Of those, there should have been over 37,333 men suitable for recruitment to the Pacific front as soldier-linguists, while women of that era could certainly do other translation work away from war zones. Of the latter theoretical total, the US Army only managed to find about 6,000 linguists by war’s end, a number deemed inadequate by all accounts, in part by expanding its search to Hawaii.

So what happened to the missing 31,000? While some undoubtedly fell outside of army draft guidelines (age, physical fitness, etc.), the yawning gap begs for a broader explanation.

The answer is that while most city Nisei attended Japanese language schools after regular school, nearly all were too preoccupied with fitting into American society, as the children of non-white immigrants, to value the added “old country” study. Mainland students especially felt their skin.

McNaughton quotes Carey McWilliams, 1944, a California journalist and editor of “The Nation”:

“The typical Japanese youngster… spent a ‘precious hour and one-half tossing spit balls at his classmates and calling his teacher names in American slang which she pretended to understand. Physically, he was in school; mentally, he was making a run around left end for another touchdown. He was restless. He counted the minutes. At the gong, he dashed to freedom.’”

Statistics from a quiet July-Oct 1941 US Army assessment, are sobering:

• The number of white American soldiers on the West Coast who spoke passable Japanese: two (of 100,000, or 0.002%).

• The number of Nisei soldiers in uniform in the mainland US: 1300.

• The number of those deemed worthy of being sent to a six-month army training course which emphasized military Japanese, based on their ability to read a few phrases from Japanese army manuals: 40 (3%).

• The number who spoke, read, and wrote Japanese proficiently: 17 (1%).

• The total number of Nisei soldiers deemed of potential value to the US Army as linguists based on ability and loyalty to the US, the latter obtained from individual interviews: 58 (5%).

What is also striking today is how the three Caucasian mid-level army officers charged with reporting their findings to the US West Coast’s Fourth Army, led by Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, were keenly aware of how deficient draft-age Nisei were in the Japanese language, yet did not or were unable to communicate their findings effectively to their top commander. Had they been able to do so, they might have forestalled the wider internment of West Coast JAs, based on their perceived value to Japan as spies and saboteurs. In the process, they would have preserved the goodwill of 112,000 toward their causes, including that from many more willing linguists, infantry soldiers, farmers and taxpayers.