Interview by Elaine Ikoma Ko, Special to The North American Post

All photos provided by Jan Johnson unless denoted otherwise.

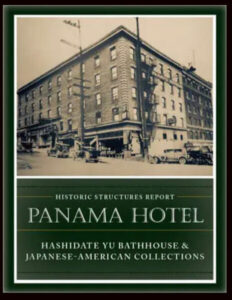

Jan Johnson is a Pacific Northwest native who has traveled extensively in Italy. She purchased the Panama Hotel in 1985. It is the oldest operating hotel from pre-war Japantown, built in 1910 by the region’s first Japanese American architect, Sabro Ozasa. Jan has preserved all the original physical structure of the hotel. Almost twenty years after her purchase, she renovated and opened Panama Coffee & Tea House, which today serves as an inviting gathering place.

panamahotelseattle.com

605 1/2 S Main St., Seattle WA

(206) 223-9242

Email: reservations@panamahotelseattle.com

Jan Johnson is a well-known name, not just in Seattle but throughout the world. She has welcomed thousands of visitors to the historic Panama Hotel and Tea House in Seattle’s Nihonmachi (Japantown) over the past nearly four decades. On any given day, you can see Jan fixing something in the boiler room, putting a new washer in a sink faucet, running up and down the stairs with a huge bundle of keys jangling from her waist (she knows exactly which ones go to each of the 102 rooms), checking in customers, conducting tours, and saying hello to her customers. But little is known about the woman who single-handedly took over this aging hotel and transformed it into a top destination for visitors around the globe. Jan’s story is one of independence, resourcefulness, and undying love. This interview delves into who she is and how she is helping to write the annals of our living history.

Q: While much has been written about the Panama Hotel, not much is known about you and your background. Can you share with our readers about you and your family roots?

I was born in Olympia, Washington, and after my parents divorced, my father resided in Olympia and my mother lived with her parents in West Seattle. Believe it or not, I do not know exactly what country my grandparents immigrated from in Europe. I do know that my father, Emerald Johnson, was an illegal immigrant, as he appeared to have no “papers” or passports and I was told that we were from a place that had “no boundaries or language.” My mother’s name was Mary Elizabeth Hill Arthur.

Yes, they had many stories, but no country was ever mentioned so I grew up not ever knowing about my family roots. Eventually, my mother remarried. So while I did hear many stories, they were just little fragments of history.

My parents were always working and now I understand why my father always had three jobs. (It was) due to his illegal status.

At around age seven, I would take the Greyhound bus alone from Olympia to my grandparents’ home in West Seattle and I liked to sit next to the bus driver for the best views.

What I remember is that I was drawn to the arts. At the tender age of seven, I would take the bus from West Seattle to downtown and transfer at First and Pike up to Broadway to The Cornish School of Allied Arts. I worked with sculpture, drawings, still life with charcoal, and I continued at Cornish through my school years. My professor kept much of my work.

I learned a lot from my father about carpentry and I especially loved working with natural wood and timbers fresh from the forests. Back then, there was no “babysitting” for kids so I traveled with him on some of his jobs. I remember the delight I had in painting the inside of kitchen cabinets and helping my dad with maintenance projects. So as fate would have it, art and working with my hands became part of my “repertoire.”

Q: So at a young age, you learned about resourcefulness and independence. Where did it take you after you graduated from school?

I didn’t know anything else but hard work. I was always extremely independent and I always worked. My first job was to sell fruit on the Olympia capitol grounds and it was my first introduction to how to make money.

I attended Seattle’s E.C. Hughes Elementary School, Olympia’s Lincoln Elementary School, Denny Junior High, and graduated from both Sealth High School in West Seattle and Olympia High School in Olympia.

I am also a visual person — I have to experience and see. I yearned to experience the arts — “the real thing” — so I wanted to visit Italy. After graduating from high school, I saved money for one-way airfare and I had $25 cash in my pocket when I arrived in Rome. I didn’t tell my mother. The bag checker at the Fiumicino airport in Rome laughed at me as I didn’t understand Italian. My first apartment in Rome overlooked the beautiful Piazza della Rotonda (the Pantheon), but had no heat — b-r-r-r! But I remember that I was continually mesmerized by the color of the light changing in the dome of the Pantheon, depending on the time of day or year.

Prior to going to Italy, I had a memorable experience that ties to Italy. I sailed on an 85-foot schooner in Mexico that was owned by a person named Captain Horace Brown and built in 1934 by Howard Hughes. We celebrated Thanksgiving that year with the family of Dan Lundberg on his boat. I was again treated to the beauty of the gorgeous wood on the boat which, by the way, is what I love about the Panama Hotel.

Years later in Italy, one day while looking for more work, I saw a job announcement for a “marinaio,” which is Italian for a male sailor. They were looking for a boat person. There would never be a female considered for this type of work. It happened to be Lundberg’s boat. I ended up working on the boat and traveled from Italy to Yugoslavia, and then later sailed on more boats in Greece. More gorgeous wood!

I lived in Italy for years, however, I never counted the years or ever referred to a clock or watch to keep track of time. All I remember is that I renewed my passport several times.

I did many things in Italy including helping to design clothing as I also loved working with textiles. Again, it fed my visual and design interests.

Q: So why did you return to Seattle and what did you do?

I vividly remember the devastation from World War II in Europe. I heard constant stories of military regimes, the nightly bombing with red skies burning with fire, hunger, and the ongoing toll on lives. I was ready to return home to Seattle which coincided with my father’s unexpected death around the early 1980s.

My first introduction to the International District was when I stayed in what was the NP Hotel on Sixth Avenue South, right around the corner from the Panama Hotel, which at that time was owned by Takashi Hori and his wife Lily. I was drawn to the neighborhood because the area reminded me of Europe — very active streets with produce and food stands and many small businesses. Mr. Hori purchased the hotel in 1938.

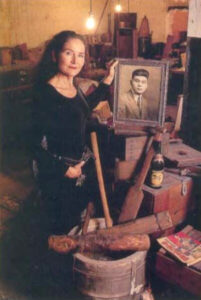

When I first met the Horis, they were most welcoming to me as there were not many Caucasian women living in the neighborhood. And Mrs. Hori sewed! Beautiful fabrics! One day, Mr. Hori was working and showed me the old Japanese “sento” bathhouse in the basement, in the original condition, built at the early turn of the century. I was AMAZED!

And then he showed me the huge amount of personal belongings and trunks in the basement of those Japanese American families who left them when they were forcibly evacuated to the concentration camps during WWII. Maybe I was naive but I couldn’t believe what I saw because I had never learned about the history of WWII. Then when I saw the trunks left behind, I saw the impact of the war here. This all deeply affected me.

Q: How did you come to buy the Panama Hotel?

One day, Mr. Hori informed me that he was planning to sell the hotel. My immediate reaction was sadness when thinking about how those trunks could be lost and recalling how the old Japantown at one time had everything one needed within just a few blocks. History was being lost.

So I asked him, “How much are you selling the building for?”

He looked at me and stated, “I already have several offers.”

I replied, “I don’t care!”

And then he laughed. But from that point on, I think he realized that I was very serious.

I made a full-price offer to him. I figured he earned it, buying the hotel years ago and working so hard to preserve it. And even after being evacuated to the camps, he came back and checked on the hotel three years later after a friend had maintained it for him. It must have been a shock because he originally thought only Japanese were being evacuated (not Japanese Americans), but later realized that he had only ten days to evacuate himself and his family. It all happened so quickly that many families asked Mr. Hori if they could store their belongings in his basement and soon the basement became full.

Photo courtesy of Hori family

And amazingly, nothing was ever taken during the three years while they were incarcerated.

I began going to local banks looking for a loan for the down payment. I was turned down at every bank. Maybe I was naive but I kept going, undeterred. It was only later that I realized I had five attributes that didn’t bode well for me at the time: I was female, single, unemployed, Caucasian, and had no credit.

Finally, I went to Bank of America and the officer gave me the loan papers, told me to bring them back to him. After I submitted the papers back, he stated, “You must be special because after all these years, people have been knocking down doors to buy this building and Mr. Hori chose you.”

I got the loan and am forever grateful to the Horis for selling it to me.

Q: What were the early years like? Were you unprepared for what it took to operate an old hotel by yourself?

There have been many surprises along the way, of course. But the building was structurally very sound. At the time, the hotel was full and we made it through the early months with the help of two Hori close family friends, Katherine and Lutus Fujita (sisters), who stayed in the hotel and helped keep the hotel running at the highest level.

In the beginning, there were more longer-term residents and they were all staying for different lengths of time, and remarkably, they all remembered when their rent was due. Eventually, I wanted to set it up as a hotel because I wanted customers to learn about the history. My early years of training paid off and the Horis spent many months training me and showing me every nook and cranny inside the hotel. They are to be credited for preserving this hotel, and I also give credit to their daughter and son, Susan and Robert Hori, who have enthusiastically supported me.

To this day, I still marvel at the all-leather flooring and the grandeur of the front steps with brass handrails. The light in the hall varies depending on the time of day and year, just like the dome in Italy. I have kept the building, (its) physical attributes, fixtures and furniture as original. I have kept the beams and still operating refrigerator cooler in the tea house. I love the unpainted old-growth timber and the original wood crates that contained the refrigerators that have been recycled into closets.

Before coming here, I knew nothing about the incarceration. You come to visit the hotel and it is a language you feel and see: no words are needed. You will immediately feel and see its own truthful story.

I also learned from my father that you never ask the government and if you lose your job, you must find another job. So the only loan I ever took out was for the down payment. It took me eighteen years to save money, a little at a time, to renovate the Panama Coffee and Tea House. I have taken pride in displaying many personal artifacts, photos, and personal stories about the local Japanese American community.

Q: What is being done with the trunks and personal items in the basement today? And what about the old sento bathhouse?

Mr. Hori tried to reach families to retrieve their items and many families told him to just get rid of the items. When I took over, I also tried to reach the families. Over recent years, many groups and individuals have begun to take interest in preserving and documenting this living history. Co-author Gail Dubrow’s book “Sento at Sixth and Main” (2004) is an extraordinary book about the hotel and she helped to research and document many items. The National Park Service funded a grant to catalogue and document 8,500 items contained in the basement. Another amazing book is “Hotel on the Corner on the Bitter and Sweet” by Jamie Ford (2009).

My goal is to turn part of the building into a museum. Today, I am just the “custodian” but others have called me the “proprietress.” I have always said that this building belongs to the community and the world and should be preserved for the young people to learn from. And, wouldn’t it be great if the bathhouse could be restored to be operating again?

My belief is “saving history saves the future.” I like to refer to the “silent voice of the Panama Hotel.”

I recall an unfinished handwritten letter, dated April 8, 1942, we found and it said, “Dear Dad, we’ve gotten pretty far with our preparation for evacuation. Everything has been packed, but kept open, and…” The letter was never finished. We eventually found the owner of the letter — it was his brother writing to his father. Now in his 80s, he said how grateful he was that it was saved and how it gave him some closure. I have many stories of families and students sharing the impact from visiting this place.

For me, it is all about prevention so this incarceration and suffering from war can be prevented from happening again.

Q: What is in your future?

I would love to return to Italy and visit and spend time with friends and family and more meaningful adventures!