By Mikiko Amagai, For The North American Post

“They always thought I was Japanese while in the Philippines. Several of us went to a café. A guy asked, ‘Do you want some Japanese tea?’ And he ran to a piano and played ‘Gunkan Marchi’ (Warship March) and then ‘Shina no Yoru’ (China Nights). They believed we were Japanese in spite of our US Army uniforms.”

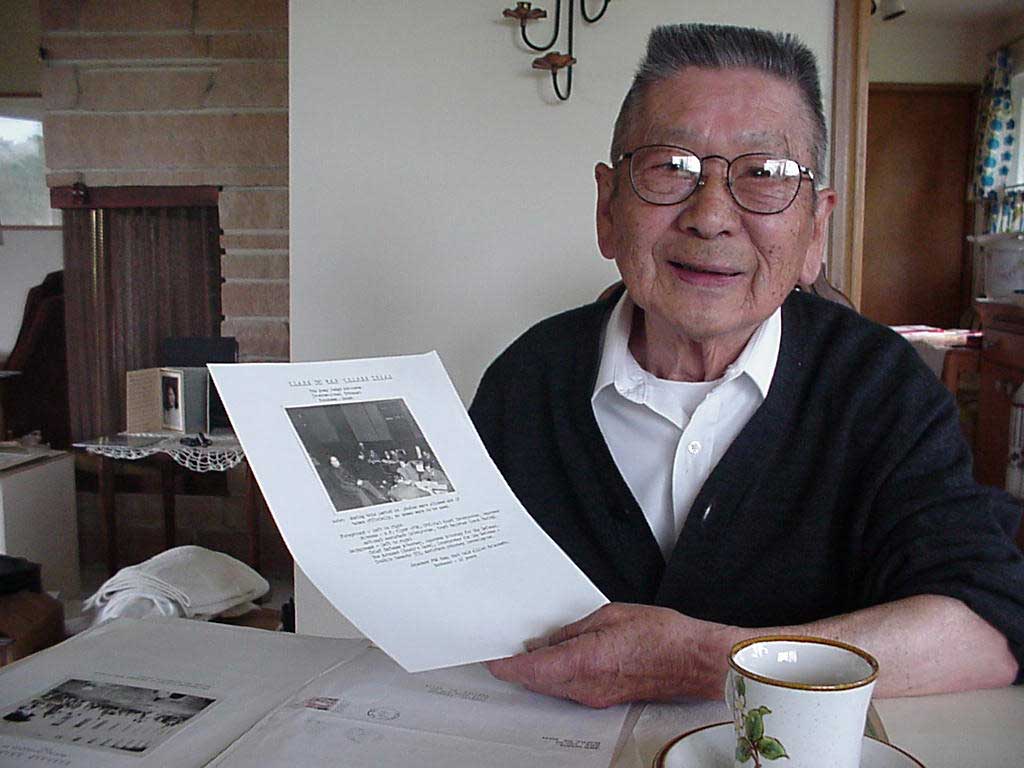

Yoshito Iwamoto remembers those days, smiling. He was sent to the Philippines and then to Japan as a MIS (Military Intelligence Service) translator during the occupation period. Perhaps, time has filtered his emotions; his story does not reflect sadness.

Yoshi was born in Wapato, Washington, the fourth boy of five children. His father came in the early 1900s from Kumamoto, where he had been a forester. He came to Puget Sound three times before but didn’t get off the boat.

According to Yoshi, “My father said, ‘The first time, nothing but Indian villages. The second time, cabins.’ The third time he saw the little villages in Everett. Then the fourth time, he was ready to land.”

As a tree-topper who was never afraid of heights, Yoshi’s father was offered a chance to own the property of a European immigrant.

“The guy said, ‘If you clear ten acres, I give you five acres.’ He (Yoshi’s father) didn’t know that no Asians could own land. He was tricked.”

Then they moved to Wapato in the Yakima Valley. By this time, Yoshi’s father had a child. He could own property and operated a hotel and pool. The guests were mainly Mexicans who worked the crops of alfalfa and wheat in spring and summer, young students to pick apples in the fall, and Japanese bachelors (dekasegi) as field workers in winter. His father died when Yoshi was a small boy and two of his brothers were raised by an uncle in Japan.

When the Second World War broke out, the family was relocated to Heart Mountain, Wyoming. They closed the hotel and left it with a friend to take care of just before the evacuation. Yoshi’s sister died as a result of a kidney operation. The doctor knew that somebody came in and shut off the drainage that caused her death.

“He asked if we wanted to sue the hospital but it would make things worse. The doctor said, ‘I hate Japan now but being a medical doctor, I still have to report the case.’ My mother and brother said ‘NO’ for the simple reason to [not] make things bad for the rest of the Japanese community.”

Yoshi agreed with their opinion but still shakes his head.

Volunteering for the army at Heart Mountain in 1943, Yoshi was assigned as a translator at the MIS Japanese Language School in Camp Savage, Minnesota. In 1945, he was sent to the Philippines on the LUPOW (Luzon Prisoner of War) team to screen and register 50,000 to 60,000 Japanese prisoners – recording their names, birthplaces, units, and places of capture or surrender.

“I always felt sorry for the doctors and nurses because they were overloaded under bad conditions: malnutrition and wounded soldiers. I remember a guy completely burned, but alive with a straw in his mouth so he could breathe. Even a “comfort girl” was there to help. She said she was a nurse but I could tell. She said she was from Kumamoto so I said, ‘Ame arare furubatten. Aso no kemuri ha kyakientai’ and she was surprised.” (The Volcano Aso is still alive and even the rain or hail wouldn’t extinguish the smoke of Mount Aso).

“Then I was sent out to jungles.”

His duty was to check the Japanese POWs working at a quarry. It was a dangerous job since he might be mistaken for a Japanese and get shot.

“I was more afraid of Filipinos than Americans. Of course, Americans never trusted us but Filipinos were worse. We looked like Japanese to them.”

The town Santa Maria was pro-Japanese. When they went to the next village, Calumba, the whole village came out and surrounded the Nisei soldiers.

“They thought we were Japanese escapees.”

In the jungle, he caught jungle rot (fungus), malaria, and polio that paralyzed him from head to toe for several weeks. Even though he suffered the diseases, the three years in the Philippines somehow left him with warm memories.

“I always wanted to go back to the graveyard to pay my respects.”

The whole unit of 3,000 men was to be moved to Japan in 1946. Due to his physical condition, he was given light assignments: to the Australian Honor Guard at the Imperial Palace; to a British documentary film crew; to Tokyo University to teach English; and to serve as Major General Willoughby’s interpreter at the 90th Extraordinary Session of the Imperial Diet, where Emperor Hirohito presented the Imperial Rescript with the new Constitution draft. Later, Yoshi became a court interpreter for the trial of Japanese “Class B” war criminals (accused of conventional war crimes).

Asked by the Army whether he would like to remain in the army for another three to four years in Japan or become a civilian court interpreter for one more year, he chose the latter.

“They sent me to the headquarters in Yokohama for court martials: for trials of Americans who committed crimes against Japanese: black marketing, murders, robbery, unauthorized break-ins, rape cases…”

Yoshi received an honorable discharge from the Army and left Japan in 1947 to go to the University of Washington.

“I had no problem in Japan, but I didn’t get to enjoy a lot of happy moments because I was at the court all the time–not pleasant memories–always working to keep up the Japanese, especially the court language that was so different from the colloquial language.”

He reflects on those days as not very enjoyable because of another reason: “All my paychecks went to my girlfriend Chifune Hasegawa. I was planning to marry as long as she didn’t object. I met her at the camp, Heart Mountain.”

He went back to the US and got married. Unfortunately, he found he couldn’t continue his education because his headaches were so bad. Yoshi instead went to work for the military transportation service during the Korean War; for this, he was honored for outstanding performance and received a Superior Accomplishment award. He worked for that supply company, a government agency, for 33-1/2 years.

“I was very lucky. All the diseases were treated, I got to see all my relatives in Japan. They were all so nice to me. I will never forget that. They welcomed me, fed me. Two uncles, they were my family. My third brother came back from Malaysia. We didn’t talk that much. He was real true Japanese-Japanese soldier, you know. He didn’t feel comfortable. At least we were courteous to each other. We slept on the porch in the sun. He had a bad case of malaria. And I had it too. We more or less rested together.”

He talks about his brother, looking into the distance as if to see beyond a wall as thick as the half a century left behind.

After Yoshi returned to the United States, Yoshi’s mother re-opened the hotel in Wapato. But it was destroyed by a fire set by a transient and she lost everything. The hotel had insurance but his mother didn’t receive any money.

“The agent pocketed it but we didn’t do anything. We just accepted it,” Yoshi said with a typical Nisei shrug.

Nisei, the generation between being Japanese and American, are in a difficult position. Understanding both sides, they don’t show much emotion.

“How can you keep it up?” I asked Yoshi.

“My mother said to hold your temper, to be charitable as much as possible, and to dedicate yourself to work.”

His modest mother’s spirit appears alive in him still. Coexisting in Japanese culture and American customs like most Nisei, Yoshi’s way of life is to try to accommodate both sides. Looking at Yoshi’s smiling eyes through his glasses, one word came to my mind: “peacemaker.”

Editor’s note. This interview, the last in the 13-article series, is reprinted with light editing from The North American Post-Northwest Nikkei, June 19, 2004. An epilogue will appear next month.