By Mikiko Amagai, For The North American Post

On February 19, 1942, two months after the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. Nearly 8,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans in the Seattle area were sent to evacuation camps. Among them, two thirds were American-born Nisei. Many of the young men would later fall into two groups: “No-No Boys” and volunteers for the army. Now that they are aging, the quiet Nisei ex-soldiers are willing to tell their unspoken stories. Having been through war themselves, they have an immense desire for peace. In this second part of the interview series, three Military Intelligence Service (MIS) veterans share their true voices.

“I forgot Japanese,” George Koshi, a 92-year-old MIS veteran, modestly said in Japanese with a perfect Japanese accent.

He was the only American legal officer in Japan during its occupation period after World War II (1945-1952) who spoke Japanese. Between George and a framed picture of his late wife, Ai, smiles his daughter, Joyce, who was born during this period.

George’s parents came from Kumamoto.

“My father first came to Colorado, then my grandfather arranged a wife for him and sent her. They met for the first time.”

George talks about his parents’ picture-bride marriage with a bashful smile as though it was his own. His parents operated a sugar beet farm in Greeley, Colorado, 60 miles north of Denver, then bought a hotel in Denver accommodating Japanese visitors.

George was the third of ten children. When he was six years old, his mother took six of her children to Kumamoto, her homeland in Japan, to give them Japanese educations as Kibei. He spent ten years from elementary to high school there. He came back to the US when he was 16 and repeated his education from elementary to high school. Then he went on to the University of Denver and its law school.

In 1940, George was drafted. After six months of basic training at Camp Savage, Minnesota, followed by another six months of infantry training, he became a Japanese language instructor. He was sent to Washington, D.C. on MIS duty in April 1941.

“We received documents from Manila when they didn’t know what to do [with them]. We studied Japanese customs and history. We were sent to Japan right after the war was over in 1945.”

“[At] first, I was the only Nikkei MIS in D.C. Later on, the Pentagon sent four more guys: Jimmy Matsumura, Earnest Yamane, Bill Kondo, and Kenjiro (last name missing) from Okinawa. We all went to Japan together,” remembers George.

Koshi was stationed as a sergeant in Atsugi, Kanagawa Prefecture, west of Yokohama. Sergeant was the highest rank a Japanese American could get at the time.

“Then, they started to commission Nisei officers including about 20 that I knew who were of lower rank.”

In 1946, Koshi was discharged from the Army but remained as a civilian legal officer for the US Government when the Japanese war crime trials started in May of that year. He was on the defense team for war crime prisoners. There were about 20 men on the team, including Japanese defense lawyers, their translators, American lawyers, and their translators.

“The trial was in English, everything. The Japanese lawyers didn’t speak English so I was on the defense for them. It was a little strange.”

He expresses a slight wry smile.

All the Class A prisoners, including Premier Hideki Tojo, were sentenced to death by hanging. All two hundred Class B prisoners, except three, were sentenced to life in prison.

Koshi was involved in the Class B trials.

“The trials themselves were fair. Even though the defense team had a chance to say what they needed to say, they couldn’t say what they wanted to say fully, I think.”

But the trials led to a puzzling ending.

“The prisoners with the life sentences by a fair trial walked away free after the Peace Treaty in 1952,” recalls Koshi.

The treaty took effect and the same day, the men from Sugamo Prison were liberated; so they only served a few years of their life sentences.

“I worked for the United States Army and I am glad I was a MIS. It was a fair trial from America’s point of view. And we, both sides, made [a] tremendous effort. We did everything we could together,” says the retired lawyer.

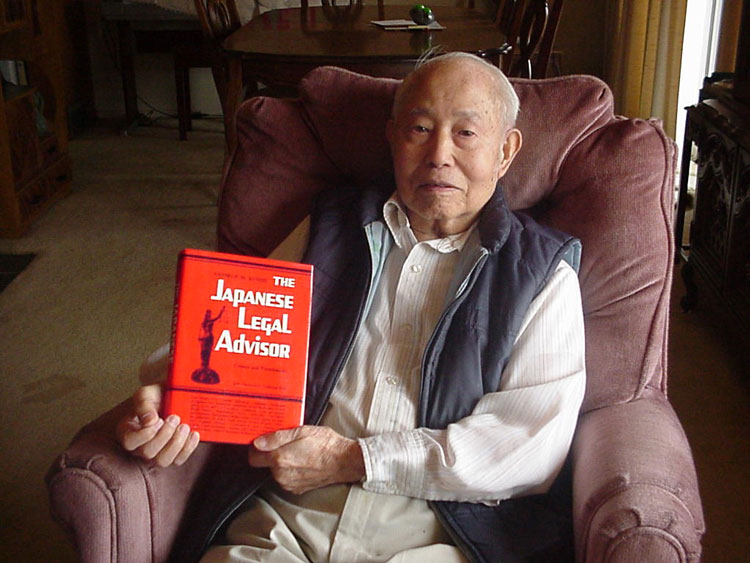

He doesn’t have any regrets. Sinking into his favorite armchair, George seems to be content with his life.

“Fulfilling life?” I asked.

“I guess it was a fulfilling past life,” he answered.

“Current life,” corrected daughter Joyce with a proud smile. It was a task that only a Japanese American, an American with a Japanese heart, could perform. He published a book called “The Japanese Legal Advisor” (C. E. Tuttle, 1970, 396 pp.). And though he is modest about it, George also played an important role in drafting the post-war Japanese Constitution. For his work, he was awarded a “kunsho,” an Imperial Order of the Sacred Treasure (Zuihoushou), Third Class, from the Japanese Government in 1974.

After retiring, he moved back to the US and settled in Seattle, the hometown of his late wife, Ai. He passed the Washington State Bar Exam in 1975 and kept practicing law until he let his license expire last year. Next to his armchair, Ai smiles from inside the picture frame as though she is saying; “George, your job is done and it was well done.”

George Koshi closed the last chapter of his life on February 26, 2004. His memorial was held on March 7, 2004 at Blaine Memorial United Methodist Church, Seattle.

Editor’s note. This article, the 11th in the 13-article series, is reprinted from The North American Post-Northwest Nikkei, March 6, 2004. The remaining interviews will appear monthly.