By Geraldine Shu, For The North American Post

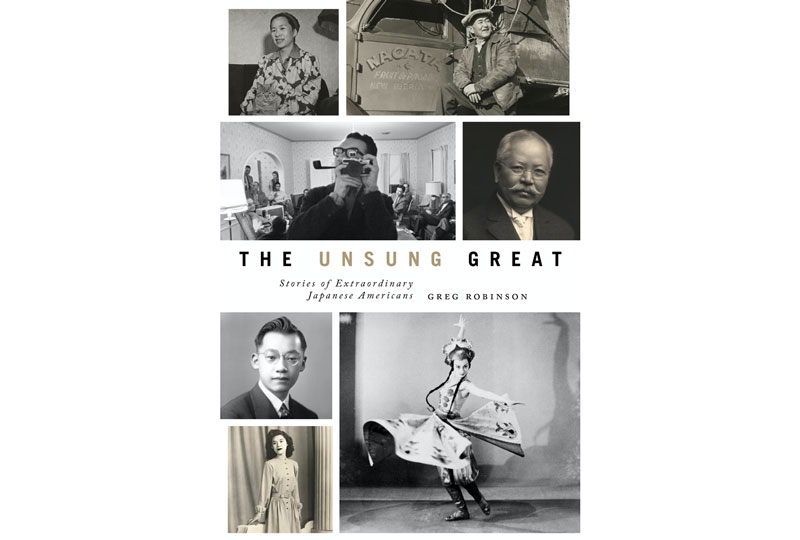

There are many subjects of interest in this book by Greg Robinson (UW Press, 2020, 312 pp.) because of chapters about mixed race JAs, writers, political and civil rights pioneers, artists and scientists, queer Nikkei, and non-West Coast locations. The best essays are those that highlight one particular person, delving under the surface to better understand their character, or one specific subject. It is clear to see which topics the author knows a great deal about because those, such as John Okada or the queer history of JAs, are expanded and more deeply explored.

It is engaging to learn about the “godmother of Japanese American redress,” a renowned ichthyologist (fish scientist), the inventor of the contact lens, two JA brothers in the US who served as propagandists for Japan, or satsuma farmers and camellia and azalea growers in Alabama. It is enlightening to read about other less known issues such as the Japanese who were incarcerated in Panama and gender-based factors where relationships between Asian men and white women were more taboo than those between white men and Asian women. Other less familiar topics covered include the wartime confinement of mixed couples and their children, comparison of redress in the US and Canada, and the JACL being the first nonwhite national civil rights organization to support equal marriage rights for same sex couples.

The author Robinson is a historian whose goal is to “challenge conventional and outmoded ideas of Japanese Americans,” the key emphasis being unconventional (and often obscure). However, one of the best chapters is about the friends and foes of the Nikkei during the war, which has little to do with unsung great JAs. For example, it is interesting to learn more about Eleanor Roosevelt, who strongly disapproved of the evacuation decreed by Executive Order 9066, which her husband Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed into existence, how the writer Pearl S. Buck was the only nationally known figure to oppose the mass removal of the Japanese, or how West Coast Chinese defended the patriotism of the Nikkei.

The numerous biographical sketches about JAs one gains from reading this book make it worthwhile. Most of these essays were previously published in San Francisco’s “Nichi Bei Weekly” and in “Discover Nikkei,” a website of the Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles.

Another book by Robinson that sounds intriguing is “By Order of the President” (Harvard Univ. Press, 2003, 336 pp.), which explores FDR’s prejudices against Japanese before World War II. It probably justified the incarceration camps to him. An additional topic which the author has studied extensively is the history of relations between Blacks and JAs and their postwar alliance for racial equality. These might prove valuable for future reading.