Yoemon Shinmasu, Life of My Grandfather in Seattle

Vol.9 The Japanese Association and Yoemon’s final days

by Ikuo Shinmasu, translated by Kimly Sok

This is a series on the life of Yoemon Shinmasu, an Issei immigrant from a small fishing village in Yamaguchi Prefecture who made his barbershop business quite a success in Seattle, yet lost his life in an accident in his 40s. Yoemon’s grandson Ikuo was born and raised in Japan and has been always interested in Yoemon’s life in Seattle. He shares what he discovered through his research.

In Part 8, I wrote about the immigrants from Yamaguchi Prefecture, the process of sending money back to Japan, and the construction of Yoemon’s new house in Kamai. This time, I will write about the Japanese Association (Nihonjinkai) that supported Yoemon in Seattle and the final days of his life.

Yoemon’s Support: The Japanese Association

In the background of Yoemon’s successful barber shop and his ability to jumpstart his hotel business in the foreign land of Seattle was the presence of a strong community created by the Japanese associations. The Seattle Japanese immigrants established a Japanese Association (Nihonjinkai) in February 1899. At first, it was a membership organization and was renamed to the Washington State Japanese Association (Washintonshu Nihonjinkai) in 1907 when it became a gathering place for representatives of the Kenjinkai (Prefectural Association) and the barber union. A different organization, the Seattle Japanese Association (Shiyatoru Nihonjinkai), was established in 1910. In April 1912, the two organizations merged to form the Japanese Association of North America (Hokubei Nihonjinkai).

Including the Japanese Association of North America, there were records of 15 Japanese Associations within the jurisdiction of the Consulate General of Japan in Seattle. The Communication Committee of Japanese in North America (Hokubei Renraku Nihonjinkai) was created in 1913 to manage all the Japanese Associations within the jurisdiction of the Seattle Consulate General which included organizations such as the Washington, Alaska, Idaho, and Montana Japanese Associations. In 1920, the organization was renamed the Communication Committee of the Japanese in Northwestern America (Beikoku Seihokubu Renraku Nihonjinkai). The organization headquarters was located in Seattle and each region had a set number of representatives assigned to oversee operations in that region. According to records in 1921, the Japanese Association of North America had 5,453 members. At the time, there were 9,066 Japanese living in Seattle which meant that about 60% of the Seattle Japanese population were members. Within the jurisdiction of the Seattle Consulate General, there were 18,401 Japanese. It is calculated that about nine thousand of them belonged to some Japanese Association.

At first, the purpose of the Japanese Association of North America was to promote unity within the Japanese community and to advance the community’s interests. However, in 1924, with the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, anti-Japanese sentiments were on the rise. In 1926, the Japanese Association of North America added promoting Japan-U.S. friendship and the rights of Japanese in American society to its mission. It shifted its focus fully to Americanization and co-existence within American society as the Japanese immigrant community in Seattle were not subject to Japanese laws or regulations. The Association was run by Seattle Japanese who were trying to co-exist within an American society filled with harsh anti-Japanese sentiments. In 1921, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), which continues to be the heart of Japanese American political activism even today, was formed by Nisei who tried to prevent the enactment of the anti-Japanese Alien Land Law. It was the core members of the Japanese Association of North America that prodded these Nisei to form the JACL.

The Japanese Associations’ operating funds were generated from membership dues and verification fees. At the time, the Seattle Consulate General delegated the task of verifying the documents and personal references of Japanese living in Seattle to the Japanese Associations. As compensation, the Consulate would distribute a set amount of funds to each association. This system, which lasted until 1918, made it so that many of the Japanese Association had plenty of operating funds.

Starting in the 1920s, the Japanese community participated in raising money for “community chests” as part of the wider Seattle community fundraising effort to secure a new source of funding. This was part of the Americanization movement within the Japanese community. To show that they were trying to live up to the expectations of American society, the Japanese community would raise money and donated it to “community chests” operated by Americans. According to records, the Japanese community donated $6,036 to “community chests” in 1921. In return, the Japanese Association received back $2,208 in 1929 and $5,125 in 1930.

The primary everyday affairs of the Japan Association were to conduct tasks such as preparing immigration documents, assisting those in need, operating kindergartens and language schools, hosting various events such as sport festivals and obon festivals, as well as maintaining the cemeteries. The Seattle Language School, founded by the Japanese Association of North America in 1902, remains the oldest Japanese language school in the United States. The association also provided support for groups such as the barber union, the hotel union, and the Prefectural Associations. It also worked to resolve the issues that the Seattle Japanese immigrant community faced such as anti-Japanese sentiments and the problem of dual citizenship. Operating in an environment filled with anti-Japanese sentiments, the Japanese Association aimed to support and to open a pathway to success for the Japanese-American immigrants, who were living between the boundaries of Japan and the United States. Yoemon was able to achieve a number of business successes because of the strong community support that the Japanese Association provided.

The Japanese Association of North America, like all the other Japanese Associations, suspended its activities during the outbreak of World War II and the subsequent incarceration of Japanese Americans. After the war, its functions were inherited by the Japanese American Association of Seattle in 1949, which still is active today.

Connection to Chuzaburo Ito, President of the Japanese Association of North America

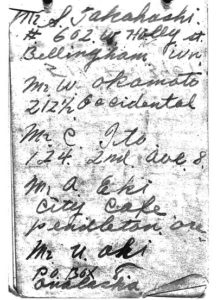

As mentioned in Part 2, Yoemon had a small 1916 notebook. On the first page of the notebook were handwritten addresses of Yoemon’s acquaintances. In the center of this page was “C. Ito”, Chuzaburo Ito, who was President of the Japanese Association of North America, the Yamaguchi Prefectural Association, and head of the barber union in 1928. It was Ito who opened the way for Yoemon to enter the barber business. Ito also was the matchmaker for Yoemon when he married Aki and he was Yoemon’s guarantor when he returned to the United States after returning home temporarily.

Ito was born in 1871 in the village of Okiura, Oshima District, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Okiura was located on the island right next to Nagashima, where Kamai, the birthplace of Yoemon, was. Okiura was about 14 to 15 km directly across from the shores of Kamai. When Yoemon met Ito for the first time in Seattle and he told Ito that he was from the neighboring island, the two men developed a hometown affinity with one another.

Ito was awarded the Showa Coronation Medal, 4th Order in 1928 for his substantial contribution to the founding and development of the Japanese Association and barber union in Seattle. The records of this award were held in the National Archives. Ito returned to Japan temporarily on October 20, 1928, and the news of his award was reported on by the Taihoku Nippo (The Great Northern Daily News). Since he planned to stay in Japan for a while, Ito asked Vice President Eihan Okiyama to be the acting president of the Japanese Association while he was away. At that time, there was a tradition of seeing off close friends and acquaintances who were returning to Japan at the Port of Seattle; so despite being extremely busy, Yoemon went to the port to see Ito off. Ito was a teacher and an elementary school principal before coming to Seattle and took a liking to people who worked hard. Ito held Yoemon’s positive attitude and passion for his work in high regard. At the port, Ito shook hands firmly with Yoemon and praised Yoemon’s efforts and success. However, this was to be the last time that Ito and Yoemon would say goodbye to one another.

Yoemon’s Final Days

Yoemon turned 44 years old on Sunday, November 4th, 1928. On that day, Aki was at home making Yoemon’s favorite botamochi (adzuki bean mochi) and they were going to celebrate his birthday as a family. In Kamai, botamochi was called ohagi and it was a tradition to eat it on your birthday. Aki went out to buy mochi rice and adzuki beans from the grocery store in the nearby Japantown and they would eat botamochi together as a family of three that night.

Aki’s birthday was on Sunday, December 23, so Yoemon wanted to take a trip with Aki for her birthday as it was thanks to her that he was able to accomplish all that he did. Around the same time, the letter from his father in Kamai, Jinzo, arrived to notify him of the completion of the house in Kamai. Yoemon was in high spirits as it was one good thing after another happening to him.

Almost 25 years had passed since he left Kamai at the age of 19. He had spent more than half of his life living abroad in Seattle. When he first came to Seattle, he was so homesick that he couldn’t sleep well at night. However, Yoemon was able to overcome many hardships and his great success was a result of his hard work in Seattle. Around this time, Yoemon decided to get a family photo of him, Aki, and Atae taken. This photo was the one used in Part 1 of this series. It would also be the last picture that he took before his death. The photo was taken by Aiko Studio, which was still in business at the time in Seattle Japantown. On the back of the photo, his oldest daughter had written “Yoemon, 44”, “Aki, 35”, and “Atae, 14”. The family’s warmth could be felt through the photo. Yoemon’s face had the dignified expression of a successful man filled with pride of his accomplishments. However, on the other hand, Yoemon’s health was deteriorating as he was experiencing dizzy spells and other health conditions. Over 20 years of hard labor and anxiety had taken its toll. Aki, who was always by Yoemon’s side, also began to feel that something was off about Yoemon recently.

On Monday, November 26, 1928, Yoemon was informed by the Seattle branch of the Bank of Yokohama that his loan was approved. He immediately went to the bank and signed off on the loan. Finally, Yoemon was now able to open his hotel.

From that week onward, Yoemon became absorbed in the preparation for the opening. Until Saturday, December 1st, he was in contact with vendors every day to coordinate the hotel opening. He had plans for the first-floor lobby to have a reception desk and sofas for guests to sit in. The opening was set for Monday, December 3rd and by December 1st, the hotel was almost ready to be opened.

On Sunday, December 2nd, 1928, Yoemon had breakfast with his family for the first time in quite a while. After breakfast, Yoemon said that he was going to go see the hotel and would be back before noon and left the house with a big smile on his face. There were still some details about the opening that bothered Yoemon, so he wanted to check on them. Aki, however, had wanted the tired Yoemon to stay home with the family and rest since it was a Sunday. Atae also was not at school, so it would have been a good opportunity for Yoemon to talk to him about school. However, Yoemon said that no matter what he was going to go see the hotel and left the house in the morning. He did not return even after noon. Aki began to worry.

References:

- Mitsuhiro Sakaguchi, Nihonjin amerika iminshi (The History of Japanese Immigrants in America), Fuji-shuppan, 2001

- Cabinet Office, Privy Council, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Home Affairs, Showa tairei jyoi jyokun naishinsho (Showa Coronation Medal Records), National Archives of Japan, 1928

- Hokubei Nenkan (The North American Almanac), The North American Times, 1928

[Editor’s Note] : This series is a collaboration between The North American Post and Discover Nikkei (discovernikkei.org), which is a program of the Japanese American National Museum. It is an excerpt from “Studies on Immigrants in Seattle – Thoughts on Yoemon Shinmasu’s Successful Barbershop Business,” the writer’s graduation thesis submitted at the Distance Learning Division at the Nihon University as a history major and has been edited for this publication.