by Jeri Okamoto Tanaka

“Walk it off.”

When I was growing up, that was my father’s solution for almost every problem. A fight with my younger brother? Go outside. Walk it off. Got a headache or a stomach ache? Walk it off. Nervous about starting a new school? Can’t figure out your homework? Walk it off. Although I didn’t understand it then, this mantra had propelled my father through life. It would one day save him and become a life lesson for me.

My Japanese-American father, who once stood tall at a stocky 5′-8″ with broad shoulders and thick black wavy hair, embodies “gaman”—perseverance, even in the face of tremendous adversity, a traditional and revered cultural trait imbedded in my father’s DNA. According to my father, showing gaman means you never complain or show pain or any emotion—you problem-solve, you look forward, you walk it off, and you endure. In our home, that also meant that you shouldn’t cry unless you were bleeding, not a scratch, but hemorrhaging. He was especially tough on my brother. I tried, but never quite mastered that turbo gaman.

The youngest of six children, my father “Mitsuru”—a second-generation Nisei—was born in 1930 and raised in Hanna, Wyoming, a remote coal-mining town with a few hundred residents. His father immigrated from Japan and found work in the mines. His mother came to America as a “picture bride” decades younger than her husband-to-be. Hoping for a life in “the land of milk and honey,” she instead landed in the harsh Wind River Range in the Rocky Mountains.

As my father told classic “you kids have it so easy” stories of walking uphill ten miles to school in blizzards, he also explained with all seriousness that life in those days was about pure survival—hunting to put food on the table, doing odd jobs for pennies, and trying to combat illness and injuries without much medical care or sympathy. As the rambunctious baby brother in a family of eight living in a three-room house without indoor plumbing, his mother’s catch-all remedy for him was to go outside, run around, and walk it off—rain or shine, scorching heat, or below zero.

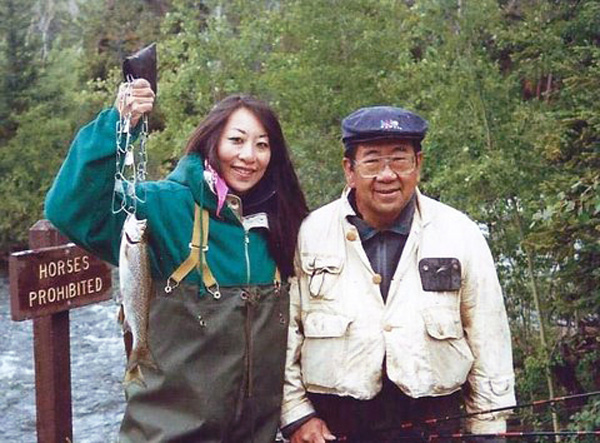

When I was a young girl, I admired but sometimes dreaded my agile father’s optimistic grit when we hiked up steep trails in the Wyoming wilderness. He expected me to follow him as he hopped from boulder to boulder. He danced like a tightrope walker crossing the rapids on a fallen tree, just to get to the perfect fishing spot.

“Come on, Jeri,” he’d say, extending his hand with an encouraging grin, his eyes peeking from beneath his lucky cap dotted with hand tied flies. “One step at a time, you can do it!”

And I’d crawl along the rocks and inch along the tree trunk using my fishing rod for balance, learning to be brave even though I wanted to cry and quit and run back to camp. A full creel and quiet time with my father, casting our lines into the river while the breeze ruffled the aspens and chipmunks chattered, were the rewards for my grit for years of fishing to come.

But I began to question the wisdom of my father’s one-size-fits-all attitude of gaman when he hurt his ankle playing church league basketball and he tried to heal it by walking it off. His ankle turned purple, then blue. It became so swollen it looked like he had a grapefruit in his sock. He couldn’t walk.

When my mom finally convinced him to see a doctor, the x-ray revealed a broken ankle, made worse by walking on it for weeks. He got a cast and was told to take it easy but, of course, he tried to speed up the healing by walking it off, eventually ripping the plaster off with his hands. And he kept on walking and wincing.

And so it went.

When my mother died suddenly after being separated from my father for many years, my then 61-year-old father returned to our family home but didn’t sleep—instead I heard him walking and pacing until dawn, night after night. He sobbed beside my mother’s casket in solitude. I’d never before seen my father cry.

My father is 84 years old now but we weren’t sure that he’d live to see another birthday after he turned 80. While walking to the gym at his senior center, he was struck by a car, smashed into the windshield, and flipped back onto the crosswalk. While he escaped broken bones, he suffered head trauma and was hospitalized for months, teetering in and out of lucidity. My once stoic and gruff father broke down once again on the eve of his brain surgery, expressing love and regret and allowed me to cry along with him.

He survived the surgery and what did my father instinctively want to do? Walk it off. Loopy on morphine, he yearned to walk and hike and take my stepmother swing dancing.

“Jeri, get the fishing knife. Cut me loose,” he begged through his delirium, fighting the arm and leg straps that kept him tied to his hospital bed for safety.

I longed to set him free from the restraints and the confusion, and to help him walk it off. Helpless, I roused my own gaman to combat and hide my feelings of fear and sorrow. This isn’t how it should end for the man who worked his way up by sheer will from the Hanna coal mines to the Air Force and graduate school, becoming a successful government executive before retiring—my dad. All I could do was pray and put on a brave face.

Then, little by little, my father’s mind and memory began to calm and the man I knew returned. Through physical therapy, he regained his ability to stand, to take a step or two, then shuffle laps around the hospital corridors. Each step lifted his spirits and he walked his way from the hospital to the rehabilitation center and then home again. It was a miracle according to his neurologist, who attributed my father’s resiliency to his fierce drive to be active and powered by his own two feet.

Gaman.

Each day he walked around and around his living room and the senior center track wearing the new pedometer I got him for Christmas. His goal, which he usually achieved, was 10,000 steps a day or about 5 miles. He kept up his regimen until my stepmother was hospitalized. At 82, my father hobbled through the aisles of Costco, leaning on the grocery cart, then hauled cases of Ensure back to the nursing home to sustain her, urging her to walk off her infirmities while he prodded and patiently escorted her for months.

After he wrecked his car and we battled over whether he should continue driving or capitulate to having a caregiver assist with housework and transportation, he threatened to walk to the nursing home every day in protest.

“It’s only 30,000 steps,” he proclaimed.

With his cheerleading, my father got my stepmother back home again where they walked a few steps together with their new caregivers every day until her passing.

Now, a widower who every so often wells up with sentimentality, my father resides in an assisted living community with beautiful grounds.

“Don’t need a walker,” he insisted, as we gingerly navigated through the rose gardens and trekked his daily route with his arm in mine for support.

A knee replacement gave him a few more steps, but his arthritic nemesis ankle and a fall recently landed him in a wheelchair. But I know that his gaman won’t keep him there.

“I’ll be walking good as new in two weeks,” he announced. For now, it’s about 100, not 10,000, steps a day, but it’s a start and, again, it’s my turn to cheer him on as he did me.

My father reminds me to start walking myself toward a healthier future too, warning me that I’m not getting any younger either. So I now aim for those 10,000 steps a day inspired by my father’s life.

As I learned from my father’s broken ankle, you certainly can’t heal everything with gaman and by walking it off. You can, however, make huge strides in health and in life just by picking yourself up and putting one foot in front of the other time and time again.

Don’t sit still and stew. Don’t shy away from the rapids and run away. Go for it. Stand up. Try. March forward. Persevere. Take my hand and, every once in a while, express love and tears and tenderness to balance that ingrained legacy of gaman.

Jeri Okamoto Tanaka is is a third-generation Japanese American whose parents were born and raised in rural Wyoming. Her writing is inspired by family history, her childhood in five western states (CO, NV, MT, OR, CA), and her experiences as an adoptive mother and community volunteer. She presently resides in Los Angeles, where she serves on the Little Tokyo Service Center board and is the Advisor and Parent Coordinator for the China Care Bruins Youth Mentorship Program, UCLA.

Jeri Okamoto Tanaka is is a third-generation Japanese American whose parents were born and raised in rural Wyoming. Her writing is inspired by family history, her childhood in five western states (CO, NV, MT, OR, CA), and her experiences as an adoptive mother and community volunteer. She presently resides in Los Angeles, where she serves on the Little Tokyo Service Center board and is the Advisor and Parent Coordinator for the China Care Bruins Youth Mentorship Program, UCLA.

Jeri’s writing has appeared in Adoptive Families magazine, China Care Foundation’s Care Package, Guidepost’s Joys of Christmas, Journal of Families with Children from China, Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review, OCA Image, The Sun, UCLA Chinese Cultural Dance Dragonfly Quarterly, and in the book “Kicking in the Wall: A Year of Writing Exercises, Prompts and Quotes to Help You Break Through Your Blocks and Reach Your Writing Goals” (Barbara Abercrombie, 2013, 248 pp.).

Editor’s notes. This article was originally published in Discover Nikkei (www.discovernikkei.org, Oct. 2015), which is managed by the Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles. While walking an additional 1,000 steps per day is recognized as helpful, “data are currently lacking to identify a… minimum threshold of… step counts needed to obtain overall health benefit.” (Hall, Katherine S. and others, 2020, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity [full-text online]).