By David Yamaguchi, The North American Post

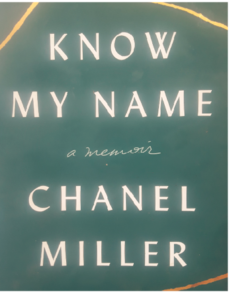

EVERY ONCE in a while, a book comes along that changes the national conversation and moves our country—and the world—forward. “Know My Name,” the September 2019 memoir by Chanel Miller, is one such book.

Ms. Miller is the previously nameless victim of the widely publicized January 2015 Stanford University sexual assault case. The case captured headlines because it involved three hot-button issues—rape, campus rape, and bias in sentencing based on race and class. It is a classic example of Have Nots taking on Haves.

The defense painted “Emily Doe,” Ms. Miller’s public name until late 2019, as a drunkard from an irresponsible family. She imbibed at a campus fraternity party to the point of passing out. She wasn’t an elite Stanford student but a recent graduate of a more ordinary school, the University of California at Santa Barbara. (What kind of grad attends a frat party?) Her sister, unable to find her, had left the party. (And what kind of sister does that?) Their mother had dropped them off there to begin with. (And what kind of mother does that?)

By contrast, Turner was a privileged white with every advantage. A member of the university swim team, he was an Olympic hopeful who swam at the London trials. He received a lenient sentence from the trial judge, who empathized with how the case had derailed Turner’s life. Turner would serve only three months of the six decreed.

The first glimmer that Emily’s female life was one of even greater promise became clear when near the case’s end, she read aloud her 7,000-word victim-impact statement, which she had drafted in a week.

Stunningly well written, her words went viral on the internet, garnering over 15 million readers within a week after their publication verbatim by Buzzfeed. That essay and the public response to it led to a book offer. It was obvious that Emily’s story had hit nerves, and that she could lay down words.

I was drawn to “Know My Name,” not because of interests in the case or the topic of campus rape, but because of Miller’s powerful writing, both in her statement and in a Google Books excerpt. It didn’t hurt that glowing reviews of the memoir had begun appearing in every major newspaper and magazine in the land, including The New York Times.

I was drawn to “Know My Name,” not because of interests in the case or the topic of campus rape, but because of Miller’s powerful writing, both in her statement and in a Google Books excerpt. It didn’t hurt that glowing reviews of the memoir had begun appearing in every major newspaper and magazine in the land, including The New York Times.

How is it possible that someone in their mid-20s could write so forcefully, I wondered? What alchemy permitted Doe’s words to make the busy US House of Representatives pause for one hour to read them aloud (c-span.org)? What allowed her narrative to prompt revising the laws of the most populous state in the land? What could I learn from closely examining her word craft?

Miller’s 357-page book had me from its first, simple lines, in which many Asian Americans might see their childhood selves. (She is hapa; her mother is from China.)

“I AM SHY. In elementary school for a play about a safari, everyone else was an animal. I was grass….”

Her thoughts on the legal process:

“I thought this would be easy. The first time I was told Brock [the swimmer] had hired a prominent high-paid attorney, I thought, Oh no. And then I thought, So? The way I saw it, my side was going to convince the jury that the big yellow thing in the sky is the sun. His side had to convince the jury that it’s an egg yolk… But I had yet to understand the system. If you pay enough money, if you say the right things, if you take enough time to weaken and dilute the truth, the sun could slowly begin to look like an egg. Not only was this possible, it happens all the time.”

Miller, on her book:

“I wrote this book because the world can be harsh and terrible and often unforgiving. I wrote because there were times I did not feel like living. I wrote because the court system is slow as a snail, and victims are forced to spend so much time fighting, rather than spending their days creating, drawing, cooking. I wrote to expose the brutality of entitlement, gender violence, and class privilege in our society. But I would be failing you if you walked away from this book untouched by humanity, without seeing what I saw: those thousands of handwritten letters… the winking court reporter. All the small miracles that sustained me. We may spend half our time wandering around, wondering what we’re even doing here, why it’s worth the effort. But living is an incredible thing, just to have been here, to have felt, if only briefly, the volume and depth of others’ empathy. I wrote, most of all, to tell you I have seen how good the world can be.”

I recommend “Know My Name” to anyone who puts words to paper, and to anyone who wants a tangible recent example of how an ordinary person can overcome a difficult situation. Others may find inspiration in its tale of how the daughter of an immigrant levered a faltering nation.