As we settle in for three months of dark, wet, and scary, it is another good season for armchair travel. The destination this time is our very own Seattle, which many of us, as natives, think we know, but don’t.

This point was driven home to me in mid-February 2020, when in my prior job as a guide for Japanese travelers, I was tasked with giving a father and teenage son a half-day tour around the city. It was just before “the wire came down.”

On paper, such tours include a number of set highlights (the Space Needle, etc.). In practice, they vary somewhat, owing to the need for the guide to route around traffic jams in the normally bustling city, as well as to take advantage of opportunities to improve his knowledge. Thus, seeing spaces in the normally filled parking lot of Gas Works Park, en route to the UW from the Ballard Locks, I pulled in to show the clients the view of the city skyline over Lake Union. I had not been there in years.

As made our way past the monstrous “steam punk” gas-works machinery, the father asked about it. I had to admit that I didn’t know what it had once been. Later at home, pursuing the question, I found that the answer helps many of the city’s attractions fall neatly into place.

Gas Works Background

Let us begin with the Chittenden (Ballard) Locks, completed in 1912. From the travelers, many of whom were globe trotters, I learned that such engineering projects are rare. They are exceptional because they are expensive to build and maintain.

The prior summer, across numerous trips to the locks with travelers, I had watched the pleasure boats ride the waters up and down. But as the boats today transit without charge, it is hard to see how they justify the locks’ great initial cost. As I read, I learned that the digging through the hard, compacted, rock-laden soil for its canals had only been possible because Chinese laborers were available to do the work when others wouldn’t.

Accordingly, in the past, there must have been high-value cargo to justify the expense. But what was it?

There are three answers. The first cargo was coal, quarried from greater Renton. That coal helped put Seattle on the map. For while many other coastal cities offered lumber, Seattle could supply both coal and lumber. Much of the “black gold” was shipped to San Francisco, where prices were better. The coal was transported by ship from the mines to railroad lines on South Lake Union. From there, train cars carried it to ships at the waterfront docks. Everywhere, the coal was used to power both steam ships and locomotives.

Besides coal, a second Lake Washington Basin natural resource was logs. Before the Montlake Cut was completed, connecting Lake Washington and Lake Union, the logs were sluiced though a ditch between the lakes.

A third product was bricks. Fired from clay quarried from beds that overlay the Renton coal, the bricks were shipped worldwide (South Africa, Peking…).

The gas works? It was a coal gasification plant. The coal was burned to make gas that was piped to nearby homes. The gas factory was on the route of the coal ships.

The timelines aid in understanding. The coal was found in Renton in 1854, where the present-day city was established in 1875. Several Renton brick companies, such as the Denny-Renton Clay and Coal Company, operated from 1892-1927. The gasification plant was active from 1906-1956. The Montlake Cut was completed in 1916, when the first ship transited the new locks and canal system to the sea.

Issei Coal Mining

Besides being of general interest, the story of the gas works and locks has two ties to the first-generation immigrant Seattle Japanese community. The first is that while few Seattle Issei worked in coal mining—it was dangerous work in an industry controlled by unions—over 2000 others did in Wyoming alone (Kazuo Ito, “Issei,” 1973).

The mining companies saw value in the Japanese for three reasons. As immigrants, they would work for less. Some had experience, from coal mining in Japan. Most importantly, they could be used as strikebreakers.

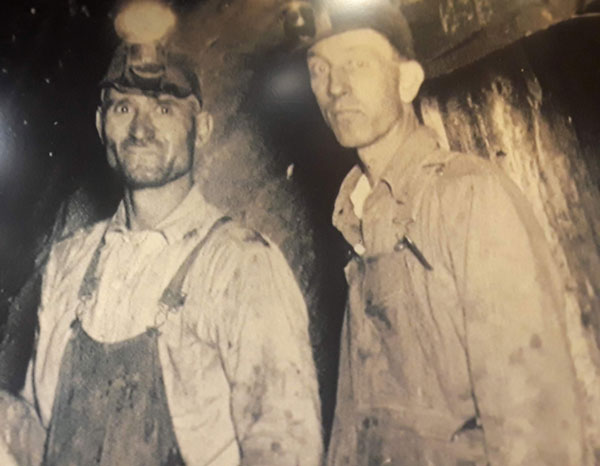

Surviving narratives of Seattle Issei on the Wyoming mines in “Issei” are harrowing. The account of Masajiro Uyeda describes his experience in Kemmerer, west of Rock Springs, from 1911.

“Using a drill with a manual crank, we bored holes six feet deep into the walls of the mine, inserted powder, and attached a fuse. A fuse one-foot long burned in one minute…

“We worked silently, the whale-oil lamp on our helmets lit… The supply of oil was carried in a small can around our waist… We all depended on this dim lamp…

“If the powder put into the drilled holes was improperly loaded, it would explode and kick back into the mine. Then the miners would extinguish the fire, throwing powdered coal over it. There was a danger that the powder, too, would catch fire… such an explosion took the lives of… Mr. Haji and his son from Okayama Prefecture…

“In addition, frequently a cave-in occurred, and it never ceased to happen that someone became a victim of instant death when a piece of coal or a rock hit him on the head…

“My father… when he was operating a box-car in the mine, caught his left hand in a machine and lost the first two joints on his last three fingers…

“Since we lived all day long in the dense coal dust, our lungs got completely black. Takeo Konma, who later had a shoe repair service in Seattle, was one who was damaged by this coal dust. If one worked for some years in the mines, even if he quit, for three years afterward, his sputum remained dark, so it was really hazardous to one’s health.

“If one was crippled by an accident, there was no compensation for it. In other words, Japanese who worked in the coal mines all tried to get a comparatively high salary at the risk of their lives.”

Ancient Bricks

Like coal mining, the story of the Renton bricks also intertwines with that of Seattle Issei. For there is a brick-lined footpath, nearly buried in the grass, in the scarcely visited northeast field of the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington (JCCCW). The outline of the path is most easily visible in the summer, when the grass is cut.

Why are the bricks buried like that, one might ask?

Well, the bricks were probably laid along the path edges in the same manner that they would be today: on the ground surface. Then, with the passage of time, and with many seasons of growing, falling, and decaying grass and leaves, the soil has built up around the bricks. Accordingly, the path must be an ancient one. It may date from the land’s development from raw land—as the Seattle Japanese Language School—during 1913-1920 (Sansei Journal, “A Seattle Map of Olde,” Feb. 2019).

Independent evidence for the path’s antiquity comes from looking closely at the bricks. Their edges are beveled. They were therefore made in Renton, during 1892-1927. The bricks were made that way because they are street-paving bricks. Without the bevels, steel horseshoe-shod horses could not find traction in hilly Seattle.