By Chuck Tasaka

For many centuries, women fought for gender equality, especially in the political forum. As early as the late 1800’s, women in Canada struggled to gain stronghold for the “Right to Vote.” Most politicians were adamant that women’s place should be in the home, having babies, raising them, cooking for their husbands, and keeping the house tidy. Nevertheless, women in Canada could run for political office.

One woman who spear-headed this movement was Nellie McClung. She and four other women delivered a petition containing almost 40,000 signatures in support of women’s right to vote. On January 28, 1916, the Lieutenant Governor passed into law the right of Manitoba women to vote, the first Canadian province to be granted enfranchisement. Then, Ms. McClung moved to Calgary and started a movement in Alberta. Successful again, other provinces took notice. Province of Quebec was the last to grant the right to vote for women in 1940. First Nations, Japanese, Chinese and S.E. Asians were denied that right since 1885.

The Japanese women who ‘knew’ their place in a male-dominated society of Japan were educated in domestic arts such as sewing, cooking, flower-arranging and raising a family. The motto was: “Good wife, wise mother.” Some of these women who immigrated to Canada as ‘picture brides, brought the old world tradition. The Issei men who were toiling in the manual labour sector in their adopted country needed wives for more stability in their lives.

For most early immigrants, life was a struggle to make ends meet. As for the sawmill workers at Hastings Mill in the Powell Street area in Vancouver, for example, daily life became more comforting. Wives would be up early in the morning to cook a hearty breakfast for their husbands as they prepared to walk down to the mill carrying lunch buckets under their armpits. That is because the men needed both hands to light their ‘roll-your-own’ cigarettes.

The daily chores for wives never seemed to end. They had to make sure the baby was fed, diapers were changed, and young children were appropriately clothed for school, so breakfast had to be served again. Housework was completed before the children returned from school. In the early afternoon, mothers went shopping to buy food for dinner. If the household had an ofuro (Japanese bath), mothers had to get the bath heated by putting wood in the stove underneath the tub. This was done before their sweaty husbands came home from work. Every Saturday was washing day and hanging clothes to dry.

When all that was completed, mothers had some spare time to teach their children Japanese and assist with their homework. In the evening, out came the sewing kits to darn socks and patch any holes in the clothing. Pants or jeans had to last almost a lifetime. It wasn’t cool back in those days to walk around with slits in their jeans. Mothers would be embarrassed seeing their children with ripped jeans because of the social stigma that they were neglectful and lazy. An old light bulb was placed inside the work stocking so that it would be easier to mend it. Nothing was wasted. Again, mothers had to be resourceful to save every penny possible to make sure there was enough money to buy groceries.

They were bookkeepers as well. Mothers took care of the finance because they had to budget the family income so that there was money left over for ‘rainy days.’ In those days, people bought only what they could afford. Radios, cameras, and expensive vehicles were unaffordable to most ‘blue collar’ workers who earned below minimum wage.

I don’t believe ‘bedtime’ was in the mothers’ vocabulary. When everyone was asleep, mothers would make sure all the dishes were washed and put away, books and newspapers were gathered and the table cleared. Only then, did they have a chance to catch up on their reading. These chores became part of their daily routine that they prided themselves on, no matter how bare the rooms looked. Whether the floor was wood or lined with linoleum, the appearance was immaculate.

In the Nikkei farmers’ case, mothers had to wake up even earlier to start their long day. Again, chores would be similar to that of the mothers in ‘Japan Town’. However, they walked alongside their husbands to the field to make sure they took care of their berries and picked them meticulously so that each year they had a chance to win the grand prize at the fair. They hoed and pulled out weeds with their husbands. Farm wives would then take a break at intervals to bring hot tea and okaki for tea-break, then leave a bit early to prepare a hearty lunch and work all day long in the field. In the evening, the chores were to have the bath ready and dinner prepared for the family.

For the fishermen wives in Steveston, Vancouver Island or Skeena, daily chores were bit different. Husbands fished for a longer period of time, and they didn’t come home each day. In the peak season, wives worked in fish canneries or the vegetable fields in Richmond for added income in case fishing was poor.

The Franciscan Sisters had a daycare center for the Nikkei children so that mothers could go to work. It was ten cents a day or fifteen cents, if a milk bottle was required. In the off-season, usually fall and winter, some mothers knew how to mend the nets, but more importantly, they had to prepare and cure fish to last them over the winter. Fish was cured in a variety of ways. Salted fish (shio-mon), smoked salmon and herring lasted a long time. Fish could be salted and dried to make ta-re. Satozuke used brown sugar. Teriyaki salmon was a common meal. Of course, sashimi was prepared for special occasions.

Tsukemono was another low cost side dish. It could be cabbage, daikon and or spinach fermented in dobutsuke or nuka. Fishermen’s wives expenses were buying vegetables and condiments. Even nori was picked and dried. A small vegetable garden was present in most households except for those who lived in cannery row houses. Women had flower pots in front of their drab cannery homes to beautify their residence.

The lives of the Japanese Canadians changed forever after the Pearl Harbor attack in Hawaii. Declared ‘enemy aliens,’ the Nikkei living on the mainland and Vancouver Island, were forcibly removed from the B.C. coast by the Canadian government. World War II was a time of uncertainty and fear of what could transpire.

By March of 1942, men ages 18-45 were sent to road camps leaving the women to take care of the preparation for the internment camps. The government stated that one could pack 150 lbs. for adults and 75 lbs. for children. Most women were petite. How could they ever carry that many belongings? They wished their husbands and grown-up sons were there to assist them. Again, mothers had to be resourceful. What to take to the internment camp? Did they anticipate the cold winters in the Kootenays? What items were considered frivolous, dolls, toys and pets? Being mothers, they probably took needles and thread, children’s clothing, medicine, and most likely kitchen utensils and dishes.

Nikkei from Vancouver Island and the north coast were sent to Hastings Park Holding Ground. The animal stalls were their temporary residences. Mothers were disgusted at the smell and dirt. They felt that the caretakers didn’t do a good enough job to eliminate the odour. Therefore, women took buckets and mops to clean out the stalls so that they could be habitable for human beings. Without their husbands and older sons, mothers had to organize and make sure the family was taken care of in their unfamiliar surroundings.

The internment movement began from late April to October of 1942. The ordeal had to be perceived from a women’s point of view. The suitcases and duffel bags had to be packed, and children needed to be clothed, obento prepared for the long train journey into the unknown. What about babies on board? Where could they breastfeed? In the evening, how did the mothers deal with crying babies and where to bunk them? Did the adults sleep on the hard wooden bench? The blinds were closed. Where were they going? Ah, the uncertainty of it all.

Once the internees arrived at internment camps, every day was another new experience for them. Coming mostly from the bustling city of Vancouver, they were placed in small cabins surrounded by high mountains. As a top priority, mothers had to be resourceful as to how they could live with reasonable comfort. Some families were given army tents for temporary shelter. One mother sarcastically stated that she didn’t have to cook and clean anymore.

Those families who were designated shacks in camps like Lemon Creek, Popoff or Bayfarm had to share with another family they didn’t know. Again, it was another life’s adjustment Nikkei families had to make. Where was the food coming from? At first, there was a canteen where families gathered for meals. Education was very important, so many of the recent Nikkei graduates became teachers in the camps. Water initially had to be hauled from Slocan River until taps were installed to be shared by families nearby. Wood had to be chopped and dried to cook meals on the pot-belly stoves. Kerosene lamps were used during the first years of the internment.

From 1942 to 1945, life in the camps had to have a reasonable facsimile of a community. Many Nikkei worked hard to have programs for children, schooling, Japanese food in the camp stores and entertainment. Some Japanese food wasn’t available so they had to make do with what they could find or grow. As a result, daikon pickles called takuan became denbazuke. It must have evolved in New Denver. Matsutake hunting was another activity done with a passion because they were such a delicacy. Gobo (burdock) and fuki (bogs rhubarb) were planted. Wherever fuki was found in the wild, Japanese Canadians grew them.

The post-war period was another huge adjustment. The government’s edict “go east of the Rockies or repatriate to Japan” ultimatum had families making a hasty decision under pressure. Going to a wartorn country like Japan or moving to the prairies or eastern provinces of Ontario or Quebec where they didn’t know anyone was like a ‘rock and a hard place.’

Fast forward to present day and it’s a miracle that most families were able to succeed in life in Canada under such oppression. I give all the credit to the Nikkei women who were able to keep the families together under duress and were able to move forward. They were the unsung heroines who were basically forgotten as contributors during those trying times. I think it’s about time that these women were given the honour and tribute.

Did all these rather mundane daily chores by the Nikkei women have any impact on the Japanese Canadians’ success? When their husbands and older sons were absent at road camps, mothers and daughters could have given up and said, “The government imprisoned us, so why do anything? Let them handle our affairs.” However, that was not the case. It was because, and I heard it so many times, “Kodomo no ta-me ni.” We do this for the sake of our children.

The Issei parents knew that their future wasn’t promising, but they could work hard to help their children succeed. They were the glue that kept the families together and never gave up. Therefore, words like gaman (perseverance), ganbaru (effort), shojiki (honesty), issho-ke-me (work hard), and shinbo (patience) pounded into their children’s minds gave them the strength to brave through discriminatory laws and rejections to become successful.

Children learn by example. They saw how their fathers toiled in low-paying, back-breaking jobs, and mothers showed undying love for their children’s welfare. Children noticed that parents didn’t buy new clothes in most cases. Instead, they sewed their own dresses and slacks. Mothers saved everything and anything that could help in the future. Therefore, the word mottainai became their mantra. Mothers injected strong characters in their children by emphasizing hard work and honesty.

As a male who was brought up in the traditional ‘men first’ mentality, I didn’t think anything of it to hand an empty rice bowl to my older sister for a refill. We didn’t think to help out with housework and laundry. If a young, married man was pushing a baby buggy, I think his friends would have pointed and giggled that he was being a sissy and hen-pecked. That was the ‘old way.’

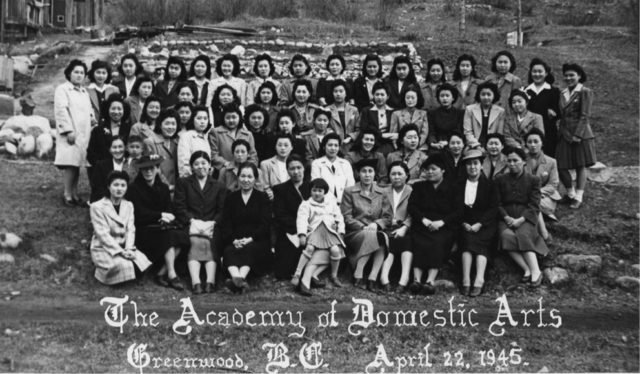

Last year, I was giving a guided tour of the Nikkei Legacy Park in Greenwood. I went on and on about the WWI Japanese Canadian veterans and the Vancouver Asahi brothers who were interned in Greenwood. This young lady replied, “You didn’t mention any women’s contribution.” Her comment caught me by surprise, so I didn’t have an answer. I replied that most mothers were too busy taking care of children and doing housework. They had no time to become involved in politics and social injustice. It took me a while to think this through. In other camps, there were people like Muriel Kitagawa, Hide Hyodo-Shimizu, and few others who worked with Thomas Shoyama and S.I. Hayakawa to petition the government for the right to vote. Sometimes, it’s difficult to ‘teach old dogs new tricks.’

Yes, the times have changed and so have the attitudes of young Nikkei. As a result, I was able to research and find several women in Greenwood who did us proud. Anna Higashi was the first female (Nikkei for sure) plumber in Canada and Molly Fukui was promoted to Post Mistress. Grace Namba taught music for the United Church kindergarten students. Catherine and Margaret Fujisawa were ordained Franciscan Sisters of the Atonement. Many more became teachers and nurses. Those who chose to be housewives did a fabulous job in their own right. Most are celebrating their Golden or Diamond Anniversary. I now have more appreciation for Japanese Canadian women’s contribution during those dark days and years. They were indeed the forgotten heroines.

[Editor’s Note] This article was originally published in Discover Nikkei at www.discovernikkei.org, which is managed by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

Chuck Tasaka is the grandson of Isaburo and Yorie Tasaka. Chuck’s father was 4th in a family of 19. He was born in Midway, B.C., and grew up in Greenwood, B.C. until he graduated from high school. Chuck attended University of B.C. and graduated in 1968. After retirement in 2002, he became interested in Nikkei history.