By Tamiko Nimura

In July-August 2019, the National Convention of JACL (Japanese American Citizens League) met in Salt Lake City, Utah. Up for consideration was Resolution 3, “A Resolution of the National Council of the Japanese American Citizens League Relating To Recognition and Apology to Tule Lake Resisters.” An earlier draft of this letter was sent to the National JACL Offices and the authors of the resolution.

Dear Members of JACL,

I am a Sansei writing in support of Resolution 3, co-sponsored by the Pacific Northwest and Northern California/Western Nevada District Councils urging a resolution and apology to the Tule Lake resisters. As a direct descendant of Tule Lake resisters and incarcerees, as a community historian and scholar, and as a mother of Yonsei children, I urge everyone to consider voting for this important step towards healing.

I know about some of the good things that JACL can do. I am writing as a former member of the Berkeley JACL. In college, I became an active member and eventually I served as its Vice President after I graduated in 1995. As I began graduate school, I was the fortunate recipient of one of the National JACL scholarships, named for the Reverend John Yamashita. I continue to admire the community work of the Seattle and Puyallup Valley chapters where I live now.

I am not a member now. I have been working on Japanese American literature, community activism, and history for many years now, but I have been reluctant to rejoin JACL, given its stance on the Tule Lake resisters.

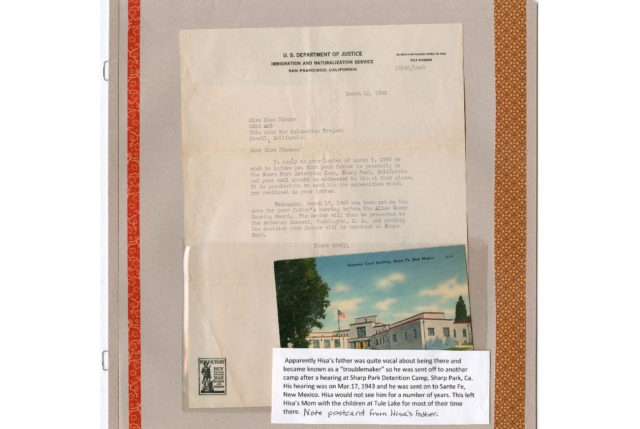

I am writing as the granddaughter of Junichi Nimura, the first Issei to be arrested at the Tule Lake segregation center in late February 1943 during the registration crisis surrounding the “loyalty questionnaire.” My grandfather was an eloquent speaker who believed firmly in the democratic ideals of the United States. Nevertheless, reports say that he urged young Nisei men to consider the consequences of the loyalty questionnaire, of serving in the armed forces for a country that imprisoned them and their families. For exercising his freedom of speech, he was imprisoned in Klamath Falls Jail, Sharp Park in San Francisco, and then Santa Fe, New Mexico. My father and his siblings did not know where he was or how to reach him for months. When my grandfather finally returned to camp from New Mexico, his one wish was to serve the people incarcerated with him at Tule Lake.

I write as the daughter of a Nisei man, Taku Nimura, and as the niece of my Nisei aunties, who were all young children at the time of the questionnaire. My father and his younger siblings were not of age to answer the questionnaire. My youngest aunts were 8 years old, 3 years old, and even a newborn in camp. But they nevertheless suffered the psychological consequences of being forcibly separated from their father Junichi when he was arrested.

I write as the niece of Hiroshi Kashiwagi, the “unofficial poet laureate” of Tule Lake, who was one of the very first Nisei to speak out about his experiences and to share them with Sansei at camp pilgrimages. I know that the stigma attached to Tule Lake and being a “no-no boy” stay with my uncle to this day. Together we worked on his first book, Swimming in the American, which was the first published memoir of a “no-no boy” and did not appear until 2004.

And I write as the co-author of the forthcoming graphic novel, We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Acts of Wartime Resistance, which I am writing with documentarian Frank Abe. The two of us are collaborating with artists Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki. As a scholar with renewed and intensive attention to Tule Lake’s history, I am learning a great deal. But I have come to understand a few things that I did not understand before.

First, I had not realized the multiple roles that JACL played before, during, and after the war. Some of the roles that JACL played, such as its involvement with Mitsuye Endo’s California State Employee case, were honorable. I had not known about the smaller legal acts of restitution that JACL worked for after the war. I understand that leaders tried to paint an unshakeable narrative of loyalty that would do as much good for the community as it could.

Given my family history, and my short but intensive study of Tule Lake history, though, I still believe that JACL leaders made a mistake in replicating and imposing the government’s definition of loyalty on Japanese Americans.

Second, I have come to see that the misunderstanding and gaps of knowledge around Tule Lake — its residents, its events, its status, and its living conditions—is one of the highest in the Japanese American community and beyond. The labels of “disloyal,” “troublemakers,” and “draft dodgers” (to name a few) follow former Tuleans to this day, and many still do not like to admit that they were at Tule Lake at all, even if they transferred to different camps after the registration crisis.

Many outside Tule Lake, both Japanese American and non-JA, do not know that residents experienced severe overcrowding, intimidation at gunpoint, violence and even torture from various sources. Many do not know that Tule Lake was given the least amount of time and resources to answer the questionnaire.

I have followed many accounts of those who were at Tule Lake, but I was still surprised to learn that George Takei’s parents were “No-No’s” through his 2019 graphic memoir, They Called Us Enemy. Even many who were at Tule Lake were unaware of the extremes of torture and the conditions of the stockade. The misunderstanding around those who answered “no-no,” and how, and why, is one of the largest gaps in our collective understanding of camp history. Often, these respondents were trying to keep their families together.

Though a comprehensive written history of Tule Lake is in progress, it has not yet been published. For our book, I have spent months combing through various sources just trying to piece together a chronology of the main players and events at Tule Lake. To date, the most comprehensive accounts of what happened at Tule Lake include Michi Weglyn’s book Years of Infamy and Konrad Aderer’s excellent documentary Resistance at Tule Lake, which has been widely shown but still needs to reach more viewers.

My point here is that this is how deeply buried, how thorny, and how torturous the history is around Tule Lake. A portion of the Tule Lake site only just received status as a National Park monument in 2008. As Resolution 3 so beautifully envisions, the JACL can and should play a role in achieving clarity around this history as the community’s largest civil rights organization.

Third, I have come to a better understanding of the word “resist,” and its origins. History, after all, is about roots. “Resist,” according to Oxford English Dictionary, is from the Old French, and it meant “to make a stand against; to refuse.” It was not until 1939—perhaps not coincidentally with the rise of fascism in Europe—that it became a definition of a collective action, “an organized covert opposition.” With similar work in education and organizing, I believe that it is time for JACL to expand its definition of loyalty by expanding its definition of resistance. I believe that as a community we have served the American ideals of both loyalty and resistance. I believe they are not in direct opposition to each other, that they are in fact closer cousins that some might have thought.

In conclusion, I urge all JACL members to consider, or reconsider, just how much longer the effects of reparations and apologies can take. We know that the minds of Americans were not automatically desegregated in public education (and beyond) after Brown vs. Board of Education. An apology to the resisters at Tule Lake will not automatically heal the wound that has divided our community for decades. But as a mother of two Yonsei girls who are descended from Tule Lake resisters, I must hope and believe that an apology will assist the long hard work of desegregation between the “loyal” and the “disloyal,” and begin to repair what has been for my family an intergenerational trauma. Kodomo no tame ni is our community’s greatest strength—it is, if you will, our superpower. We invoked it recently to mobilize on behalf of “tsuru for solidarity” for the children detained in Texas and at the United States border. We owe it to our children, those children, and future generations, to begin the difficult work of healing.

I am not a member now, but I would seriously consider rejoining if the resolution passes. I believe that others feel the same way.

With respect and hope, I urge JACL to pass Resolution 3.

Sincerely,

Tamiko Nimura

Tamiko Nimura is a Sansei/Pinay writer, originally from Northern California and now living in the Pacific Northwest. Her writing has appeared or will appear in The San Francisco Chronicle, Kartika Review, The Seattle Star, Seattlest.com, the International Examiner (Seattle), and The Rafu Shimpo. She blogs at Kikugirl.net, and is working on a book project that responds to her father’s unpublished manuscript about his Tule Lake incarceration during World War II.