FOR THIS MEMORIAL DAY, let us remember the peace-directed work of Nisei U.S. Army translators at the end of World War II. A few such men yet remain among us. They read this paper weekly.

The passages below come from the translated diary of Nomura Seiki, a Japanese soldier hiding in a cave in Okinawa. Who better to tell the tale?

SEPT. 12, 1945 (Wednesday), partly cloudy and windy

After sundown, Jihei, who was on cooking duty and had gone outside, came rushing back into the bunker.

He was holding three boxes of U.S. army field rations and a piece of paper. “This was left at the entrance,” he reported as he held out the paper to Sergeant Nishi.

Everyone moved forward… at once and surrounded the sergeant. Without thinking, I too got up… and stood behind Sergeant Nishi and strained to get a look at the… paper….

The following had been written with a pen in a fine hand:

I have heard from a group leader who was in the former heavy field artillery bunker in Yonabaru. I will visit tonight, so I beg you not to attack me. (The password is “mountain and river.”) 9/12/1945

From a former war buddy

To everyone in the military field storage bunker

My immediate thought was that the… American forces would… recommend that we surrender….

Instantaneously, a feeling of unease filled the bunker. This was not a time for us to relax. Our American counterparts were probably already approaching the entrance to the bunker….

The message… elicited various responses: if they come, should we kill them? Could we escape somewhere before they arrived? Or should we hear what they had to say and then take action? It wouldn’t be too late. We reached a conclusion: we’ll attack them and blow them up.

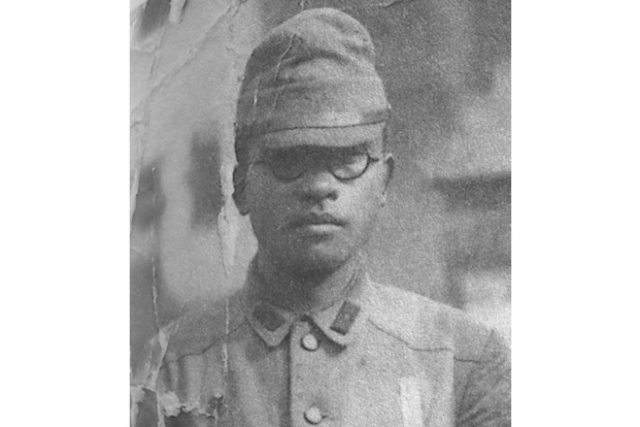

It was at around nine in the evening. Jihei and Uchimura, who had been waiting outside, guided two middleaged men into the bunker. Both were wearing American uniforms. One looked like a Nisei, and the other was a bespectacled intellectual. As they said hello and smiled, they distributed cigarettes and caramels to each person in the bunker.

Then the bespectacled one slowly started to speak, choosing his word carefully. He began by saying,

I am someone who, like all of you, fought American troops here on Okinawa. But now, wanting to help even one of my many brothers, I became a member of an American forces pacification team and have been doing this work.

He then explained that Japan had surrendered unconditionally to the Allies on Aug. 15, and that because our obligations as military men were over, we had to return to reconstruct our ancestral land—each of us—and the sooner, the better. Military units from the continent and points south were already returning, one after another, to the homeland. And he explained our position and the action we should take.

“Japan’s unconditional surrender!!” I was shocked by these words…. Although I’d known the war situation was not favorable, I had hoped against hope for a cease-fire. “Unconditional surrender” were words I couldn’t believe.

Their answers to our questions were clear, and there was no room for even a shred of doubt. In response to our questions about the situation of our buddies who had already surrendered and, of course, questions about the war, their statements were reasoned and coherent…. But we still weren’t inclined to believe everything they said.

This was the first we’d heard about Japan’s surrender, and we couldn’t respond quickly. We asked to be allowed to think about this until tomorrow evening, and everyone asked the pair to be sure to tell American troops in the area not to attack, just for tomorrow. They said, “This is eminently reasonable. Tomorrow night we’ll bring proof so that we can convince you, so please think carefully about all this. And we’ll be sure to communicate with American troops in the area,” and then left the bunker. Although overwhelmed by feelings of desperation, we saw them off. “Japan’s unconditional surrender.” If this were true, then our interpretations of the actions that American troops were taking against us were dead wrong…. the detailed knowledge of Japan’s surrender made it difficult not to interpret our actions as resistance to American troops carrying out moppingup operations in the area.

SEPT. 13, 1945 (Thursday), clear and windy

We talked all day, half-believing and half-doubting what the pacification team members told us last night…. No matter how much we talked… without seeing the evidence the pacification team said they’d bring, conversation was pointless….

It was around eight in the evening. The same two members of the pacification team… arrived with conclusive evidence of imperial Japan’s surrender. First, letters from our war buddies in units that had been attacked and surrendered were distributed…. The letters explained Japan’s unconditional surrender and urged us to surrender right away. Then they showed us copies of the “Potsdam Declaration,” which Japan had accepted; the emperor’s “Surrender Rescript;” and the “Surrender Instrument” from the deck of the USS Missouri. There were also orders from Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, the top official overseeing the occupation of our country, and issues of the Asahi, Mainichi, and Yomiuri newspapers that had pictures and articles about the Aug. 9 “Soviet Invasion of Manchuria,” the “Damage from the Atomic Bombs” dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki….

The seven of us stared silently at the evidence—its meaning was all too clear. I felt as though my whole body had suddenly collapsed…

Then after recovering from this feeling… I was assailed by an inexpressible anger. Who or what in the world was the object of my anger? I couldn’t say. I stamped my feet on the floor like a child and screamed…. I felt the urge to run like a cannonball right into the center of the American camp. In the end, even as I was being attacked by these… feelings, I agreed with everyone else that we should surrender….

Even if I acted alone and raced out of the bunker, the surrender of Japan as an actuality wouldn’t change, and the mop-up operation the American troops would launch in the wake of such an action would be directed continuously at all the Japanese soldiers in the vicinity…. Rather than rant and rage, I kept my thoughts to myself, left the group, and… walked to the back of the bunker.

SEPT. 14, 1945 (Friday), clear

Just before daybreak, seven of us, with Uchimura in the lead… climbed the small hill in front of the bunker to wait for the American troops coming to meet us. Uchimura had on a white headband and wore a uniform with a warrant officer’s insignia on the collar.

When we got to the top of the hill, the five men who had been hiding in the field artillery bunker joined us. The twelve of us went out, all together, to the edge of the hill and sat down in the grass… the sky gradually began to brighten.

To someone accustomed to living in a bunker, the bleak landscape seemed unreal. Off to the right, at the foot of a hill in the distance, a lone farmer… was using a horse to plow a field….

At that moment I heard the faint sound of an engine behind me, and when I turned around, a large olive green truck was bouncing along a grass field and rushing toward us. Everyone now saw it, and a feeling of unease immediately swept through the group. It was an American army truck.

They really were coming! I felt as though I were being attacked by a loneliness I can’t begin to describe. As the truck drew closer, those feelings intensified and overwhelmed me. I could only think of the phrase, “Do not give up under any circumstances” in the Field Service Code. I was now facing a humiliating fate I never could have imagined, not even in my wildest dreams, and blankly stared at the truck. I could see that the pacification team members… and two American soldiers were on the truck. As it approached, Uchimura and Jihei got up, and I did the same, though not very enthusiastically. The truck stopped at the bottom of the small hill. The two pacification team members and four American soldiers with automatic weapons slung over their shoulders waved to us and jumped off the truck.

We went down the hill in single file with Uchimura in the lead… and me lagging behind. We lined up in front of the… American soldiers, forming a single line…. We were a pitiful sight, and an icy wind blew through the grass as if it were mocking us. The American soldiers read us instructions, which the pacification team members translated into Japanese.

The soldiers then tossed all our weapons into a large artillery shell crater filled with water, and we got on the truck. The pacification team members told us our destination was Ishikawa….

[From “Leaves from an Autumn of Emergencies, Selections from the

Wartime Diaries of Ordinary Japanese,” Samuel Yamashita, Univ. of Hawaii Press, 2005, 330 pp.]

P.S. Private Nomura would go on to a career in law enforcement, to marry, and to become a father to two children. Today, they are probably only a few years older than me.