Strong Ties to Ehime, Great Success in Seattle

By Professor Ryoko Sato of Ehime University for North American Post (Translated by Bruce Rutledge)

The success of Uwajimaya in Seattle has garnered attention in Japan. Ehime University, one of Japan’s national universities, formed a study unit about Uwajimaya’s history and current business success as part of their glocal research project. The university is located in Ehime, where Fujimatsu was born and raised. Professor Ryoko Sato who leads the study visited Seattle several times last year to interview members of the Moriguchi family. She articulated her findings about Fujimatsu’s life from Ehime to Seattle for North American Post.

A Mikan Grower from Yawatahama Moves to Tacoma

It’s said that the very first Japanese immigrant to set foot in Washington state was Nokyuhachi Nishi from Ehime Prefecture, who came through the Port of Seattle in 1881. He was from Yawatahama, Nishiwagun (today’s Yawatahama City) in the southwest corner of Ehime Prefecture.The founder of Uwajimaya, Fujimatsu Moriguchi, was also from Yawatahama.

Fujimatsu Moriguchi was born in 1898 to a family of mikan growers in Yawatahama, Kawanazu (today’s Kawakami Kawanazu, Nishiwagun). He was the eldest of five children, with three sisters and a brother. Yawatahama was a farming and fishing town, and people split their time between the two. The main farming crop was mikan oranges. Mikan were introduced to Yawatahama in the Meiji Era. Today, the region is known nationally for famous mikan brands such as Maana and Hinomaru, but back then it was a period of trial and error. The Moriguchis operated a small-scale farm. According to Fujimatsu’s second son, former CEO of Uwajimaya Tomio Moriguchi, the farm “had a small field, with about 30 mikan trees.”

While the farm was small, the eldest son Fujimatsu surely expected it to succeed. When he graduated from middle school, however, he left home and began working in the neighboring town of Uwajimaya. He spent several years there learning how to make and sell food like jakoten, satsuma-age and kamaboko fish paste. After this, he headed to the US.

More than a few people left Yawatahama and Nishiwagun for the US around this time. If you compare the number of people who left Okinawa, Kumamoto, Fukuoka, Yamaguchi, Hiroshima, Okayama, Kochi, Wakayama, and other prefectures, the exodus from Ehime was relatively small. But if you look at the trends in Ehime, you see that as many as one-third of the population in the coastal cities left. People left in especially heavy numbers from Johaku, Kawanazu, and Annamura. Some of those who left found success overseas, and that news made it back to Yawatahama. For example, Nokyuhachi Nishii ran a restaurant in Seattle, and a hotel and dry-cleaning business in Tacoma. After that, others who succeeded overseas came back and brought more of their neighbors to the US. People from Nishiwagun had a network of sorts in Seattle and Tacoma. Many of the people from this region ended up operating restaurants or hotels. Others worked as cooks. Fujimatsu chose the food business, and probably followed the path paved by others who had succeeded before him.

The Fish Merchant Meets Mr. Tsutakawa, Starts Uwajimaya

Fujimatsu arrived in the US in 1923 at age 24. At first, he stayed close to people from Kawanazu who had settled in Tacoma and began working.He started in farming, moved to a restaurant, then switched to the Main Fish Company located on Main Street in Japantown.The Main Fish Company was opened in 1904 by Iwayoshi Kihara, who came to the US from Hiroshima in 1898.He was known for his skillfulness among the pioneer-like Japanese fishing community in Seattle. Fujimatsu, who studied food processing in Uwajima back in Japan, was probably picking up knowledge about the fish business in the US while working at the store. The Main Fish Company was also engaged in selling miso, soy sauce, rice, and other items to Japanese working in the lumber business.

Shouzou Tsutakawa was another man working at Main Fish Company. The Okayama Prefecture native came to the US in 1902. In 1905, he and Jiro Iwamura jointly formed a US-Japan trade association. In 1914, Tsutakawa took over the operation and changed the name to the Tsutakawa Association. The members went to the camps where the Japanese working in lumber and on the railroad lived, got their orders, and delivered the goods. They didn’t only deliver food products — they dealt in clothing and artwork as well, and Tsutakawa found his business growing quickly as the Japanese who didn’t speak English relied on him. In 1921, he opened an office in Kobe that exported lumber and hardware to Japan.

Fujimatsu and Tsutakawa, both dealing with Japanese customers in business, would soon become acquaintances. Fujimatsu seemed to have learned from Tsutakawa’s business, and he realized opportunity waited in Tacoma as well. He also started to see that he had certain skills that the Main Fish Company and the Tsutakawa Association didn’t have. That skill was what he learned back in Uwajima in Japan: making jakoten, kamaboko, satsuma-age and other Japanese specialties. There was no store offering these items. Fujimatsu decided it was time to start his own operation, so he left Main Fish and returned to Tacoma, where in 1928 he founded Uwajimaya Shoten, the precursor to today’s Uwajimaya. He called his younger brother Saisuke from Ehime to help him with the new business. Saisuke manned the Tacoma store while Fujimatsu ran the outside business. In the morning, he’d make kamaboko and satsuma-age, and in the afternoon, he’d load the food onto a truck, and sell it to Japanese men working on the railroad, in the fishing industry, the farms, and the lumberyards.

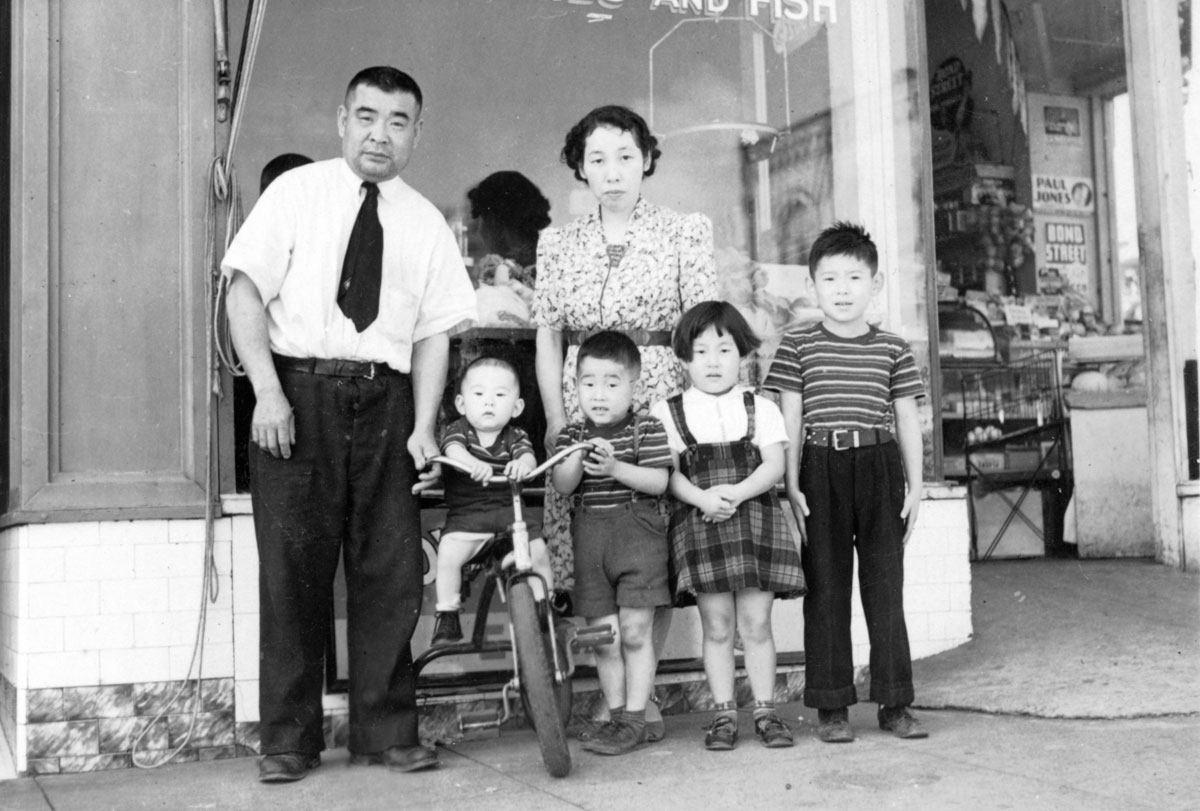

Marriage to Sadako, Children’s Names Reflect Love of Ehime

Fujimatsu’s diligent efforts caught the attention of Tsutakawa. He had nine children, and he saw Fujimatsu as a suitable match for his third daughter, Sadako (born in Seattle in 1907). Tsutakawa got Fujimatsu and Sadako together. The two courted for two years before marrying in 1932. They built a new home in Tacoma and managed Uwajimaya. Sadako returned to Japan for awhile to learn the finer points of being Japanese from her grandmother. Sadako had a taste for haiku, calligraphy, noh, kabuki, and talent in the arts and music, while also contributing to the work at Uwajimaya. She was an intelligent, capable woman.

The couple gave Japanese names to all seven of their children – four boys, and three girls. “My father planned to return to Japan,” Tomio repeated. Someday he’d return. The Japanese names were a sign that they would raise their children in the Japanese way. The eldest son of a farming family left Yawatahama for America because he wanted the best for his family and his home.

When eldest daughter Suwako was 4 (she was born in 1935), the family sent her to Yawatahama. This was just before the outbreak of war in the Pacific, so this was probably a move to protect her. “But it wasn’t only that, I think,” said Suwako. She flet that the family also wanted her to experience life in Japan. Suwako returned to the US two years after the war ended. She was 13. “There were some difficult times, but because I lived there, I can speak Japanese,” she said. “That’s a good thing.”

A scary face, but a friendly person

The common line on Fujimatsu was that he was quite strict, but he was determined to raise his children as Japanese. At meal time, he would not excuse his children from the table until they had finished every last bite of food. He was also strict about what time they should be home. Fujimatsu had an unbending stubborn streak. He was a stereotypical traditional Japanese dad – reticent, hard-working, but liked to smoke and drink and a good game of go or shogi. That severe quality in Fujimatsu “was probably a good influence on Uwajimaya’s operations,” said eldest son Kenzo. “Our character is still influenced by father’s severity.”

While he had his severe side, Fujimatsu was also a kind person who wouldn’t abandon those in trouble. “Dad was scary looking, but he was a sweet person,” Suwako said with a smile. “He would invite all kinds of people to our house for a meal, let people without cars use one of our delivery trucks.” Sadako never questioned this largesse. “Mom would always be having exchange students over to eat ochazuke,” Tomio recalled. Suwako said, “I don’t remember eating dinner with just the family. At New Year’s, there would be more than 100 people over!” Fujimatsu liked children. When they came by the store, he would ply them with satsuma-age and botan candy.

Forced Internment, Reviving the Business after the War, onto the Next Generation

In 1939, their third son, Akira, was born. In 1942, the forced relocation of Japanese and Japanese Americans to concentration camps began. While Suwako was in Japan, the rest of the Moriguchi family were sent to Pinedale and Tule Lake concentration camps. Hisako was born at Pinedale, while Toshi and Tomoko were born at Tule Lake, making it a family of nine. After the war, the Moriguchis moved from Tacoma to Seattle and re-opened Uwajimaya in Japantown. In 1960, Suwako gave birth to a daughter, Jamie. It was Fujimatsu’s first grandchild. Tomio felt that this event changed Fujimatsu in some way. “I think that once his grandchild was born here, his desire to return to Japan waned,” he said.

Two years later, from April to October 1962, Uwajimaya exhibited at the World’s Fair. Participating in this fair was a dream of Fujimatsu’s. The big break in Uwajimaya’s history came after that. The fair had brought quite a bit of attention to Uwajimaya, and people of different backgrounds (not just Japanese) started visiting. However, Fujimatsu was breaking down physically under the strain of the fair, and he needed help. His son, Tomio stepped in with a determination to operate the family business successfully. Tomio had taken a job with Boeing after graduating from the University of Washington engineering school. He resigned his position at the airplane maker and joined four of his other siblings to take over operations of Uwajimaya. That same year, Fujimatsu passed away at the age of 64.

“It was too late.” Both Tomio and Suwako used this phrase at the beginning of their interviews. What they meant was it was too late to find out much about Fujimatsu, who had been dead for 55 years.

But the other side of “too late” is that we should have valued him more while he was alive. The stories of Fujimatsu, Sadako, and other ethnic Japanese immigrants retain a certain dignity. That thought can’t be too far from the truth.

About the Author:

Ryoko Sato is a professor at Ehime University in Japan. She was the leader of a Uwajimaya research project hosted by the university’s “glocal” (think globally, act locally) research unit. From last year to the beginning of this year, they visited Seattle to talk to members of the Moriguchi family who serve as executives of Uwajimaya and to study the stores’ operations.

About Ehime University’s Glocal Research Project

The success of Uwajimaya in the Pacific Northwest has garnered attention in Japan, inspiring this research project from Ehime Prefecture, a place the Moriguchi family holds dear. Ehime University’s glocal regional research unit dispatched a team twice to interview the Moriguchi family and research Uwajimaya’s customers.

The research analyzed how something local like Ehime could grow in consciousness and skill to spread into something “glocal.” Uwajimaya, originated in Ehime, is considered the most successful Japanese supermarket in the US, and it has connected Japanese immigrants to their home country. The research team found that the experiences of Uwajimaya could offer a roadmap for other local Japanese businesses looking to operate overseas.

Last September, Professor Ryoko Sato took a survey about Uwajimaya, which had become a symbol of Asia to Americans. This March, the team surveyed a wide variety of customers at the Seattle and Bellevue stores to get a better sense of the shape of Uwajimaya in the community.

Uwajimaya’s history started by selling to laborers at their work sites, moved to Seattle after the war, and then saw an increase of visitors to the store. Today, it rides on the wave of the Asia Boom and attracts people interested in Japanese culture. “It is mixed up with Japanese American identity, but what essence of Japan will remain,” asked Sato. “Ehime is deeply interested in what is considered important here.”

Part of the survey can be seen (in Japanese) at http://ipst.adm.ehime-u.ac.jp/glocas/. The team plans to present its research at future international forums.