By David Yamaguchi

The North American Post

After visiting the Japanese section of Lake View Cemetery (July 21 issue), I could not help but turn to the pages of Kazuo Ito’s “Issei” (1973; out of print) to see what has else been written of those old grave markers. From those passages, it was impossible to resist extending the story to Mount Pleasant Cemetery on Queen Anne Hill. For at Mount Pleasant, Japanese graves even older than those at Lake View are described as having been present in 1957. They include sixteen graves pre-dating 1911, including those of “Tsuna Kinzo, June 1890,” “Yuki Miyauchi, August 1890,” and “Tamejiro Ono, age 19, [of] Hiroshima, June 1891.”

On setting out for Mount Pleasant with a photographer, I had three questions. Why are Japanese graves present there at all, so far from the International District that housed early Japanese pioneers? Where are the graves located in the cemetery? And does anyone still visit them today?

The answer to the first question seems lost in the sands of time. Certainly the Mount Pleasant grounds are ancient, dating to 1879, as compared to 1872 for Lake View. It may be that the burials at Mount Pleasant began before there was such a thing as “a Japanese section.”

To address the second question, we began wandering the Mount Pleasant grounds. As they are vast, comprising 40 acres like Lake View, my realistic goal was only to gain a general sense of the place, before inquiring at the office on a later business day.

And then, as if guided by spirits we found ourselves walking among Japanese graves! They included the vertical monument I believed would be the easiest to find, that for 23 Great Northern Railroad workers killed in an accident near New Westminster, Canada, in 1909.

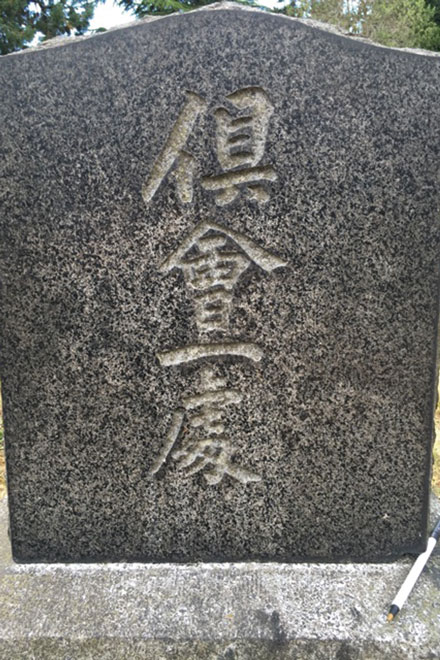

The face of the monument reads, “Kueissho,” which, as translated in Ito, means, “to meet together at one place.”

The reverse, in translation, reads, “For the 23 men killed by a railroad accident near New Westminster on the Great Northern Railroad, Canada Line, on January 28, 1909. Erected by the North American Japanese Chamber of Commerce, February 1938.” Apparently, the men, likely contracted in Seattle, were riding a locomotive that overturned.

Around the monument for the railroad workers there are four unrelated ground markers for individuals. Made of concrete, and arranged by the North American Japanese Association (whose similar work is evident at Lake View), they include those of 22-year-old Tyosuke Fukamoto and of K. Hashizaki (photos). The latter’s grave especially made us feel good, for even after over a century, someone before us had recently visited, and left flowers that had dried in the summer sun.

At this writing, I do not know where the remaining documented pre-1911 Japanese graves are at Mount Pleasant, nor whether they are grouped or scattered. If knowledgeable readers can let me know, I can share what I learn with others in this space. (The cemetery office charges for inquiries on multiple graves.)

I believe that knowing about the Mount Pleasant graves matters because they reveal the history that our predecessors made the effort to write down in stone for us. Perhaps they wanted us to appreciate the antiquity and significance of their blood and toil to the development of the present-day Pacific Northwest.

I wonder if they also foresaw that the railroad accident would be left out of mainstream history accounts. For example, no mention of it is made in a detailed online summary of Vancouver-vicinity railroad building during 1887-1910 (www.surreyhistory.ca/rrea.html).

For readers who would like to view the Mount Pleasant graves themselves, begin by finding the cemetery map on the Internet. Then drive from the southern entrance toward the northeast loop accessing the Old Chinese burials. Park at the southwest corner of this loop. On foot, look for an angel nearby (pictured), who gazes north along the west shoulder of the road you came in on. She rests beneath what appears to be a small flowering cherry. Follow her view about 30 paces further to the railroad workers monument. For completeness, the curb near the monument reads, “section 100F, lot 107.”

After viewing the graves, it is worthwhile to also see the memorial for the victims of the Valencia shipwreck, directly east within the northeast loop. According to Wikipedia, that disaster led to the building of a lighthouse and a shipwreck survivors’ trail along the outer coast of Vancouver Island.

For Nikkei readers, the Valencia monument helps lay the context for the Japanese graves described above. In the early 1900s, the Pacific Northwest was still rough country being carved from the wilderness. Our predecessors were among those doing the hard, accident-prone work involved during the decades following the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, when few others were willing to do so.

P.S. Only after returning home did we grasp the depth of our luck in finding the Japanese graves we did. According to historylink.org, Mount Pleasant housed 60,000 graves by 1999. So to find either the railroad monument or any of the other documented pre-1911 markers, our odds were 23+16 divided by 60,000, or less than seven out of 10,000!