By Yoshikazu Nakajima

Translated by Mina Otsuka

For the North American Post

To America

About four years later, as he had gained more experience and his training seemed to be going smoothly, Horitomo thought about what he would be doing in the future: then he imagined himself in 15 years. As he worked as a tattooist, he came to understand more deeply about how tattoos are seen in Japan and how Japanese society had dealt with tattoos. In such a society, he would be working as a tattooist. It was such a vivid sight.

“To tell you the truth, what I envisioned in 15 years was not very attractive to me. It might be because at that time, Japan seemed like such a closed place and I felt like I was suffocating just by the thought of living there. It wasn’t a healthy state of mind. So I began to think about giving a second shot at moving to America, the possibility that I had given up on once.”

How would a tattooist, who had gained much experience in Japan, change in a new country, America—it was difficult for Horitomo to predict his own future, but because of it, he says that felt “great excitement” in his heart.

He told Ryudaibori about his worries. As Ryudaibori had already known Horitomo and his personality, he helped Horitomo get his visa and agreed to have him work in his place. It was a bond formed by tattoos. In 2007, Horitomo moved to America and started working at Ryudaibori’s State of Grace.

Introducing Authentic Japanese Traditions

According to Horitomo, at that time there were already a number of tattooists in America who could tattoo traditional Japanese designs. A good number of people liked Japanese tattoos, too, as he saw them frequently.

But he noticed that there were some problems. For example, many people who had tattoos of a Buddhist image did not know its meaning, and sometimes the image itself was incorrectly designed—jyo-haku hung from the wrong side of the shoulder or the sword was in the wrong hand. Horitomo was especially bothered by the incorrectly designed tattoos of fudo myo-o.

Fudo myo-o has an important meaning for Horitomo. Although he didn’t learn about it until later in life, he was already fascinated when he saw fudo myo-o in a book of Buddhist paintings in a library. He was still in elementary school. Later, when he thought about what to do in life, he felt that he could get some power from it. When he was training in Yokohama, he often went to a nearby temple which had a statue of fudo myo-o, and bowed, thinking that it would guide him in a good direction. So he was greatly disturbed when he saw fudo myo-o designed incorrectly.

As he wanted other tattooists to correct such designs and to have some background knowledge, he published a book about fudo myo-o in 2011. The book has sketches of fudo myo-o which can be directly used as tattoo designs, its history, and Horitomo’s explanation of the design. It has 185 pages and is written in English. The title of the book is Immovable—Fudo myo-o Tattoo Design by Horitomo, and it was published by Ryudaibori’s studio. Horitomo says that the book was well-received. With the good reception of his first book, Horitomo published Monmon Cats, which I introduced in the beginning of this article, two years later.

What He Expects from Japan

Horitomo’s original intention for writing Monmon Cats derived from his vague wonder about the calico patterns on his cat—he wished that they were more clearly shaped. Gradually he came to have the feeling that he wanted more Americans to be familiar with and enjoy tattoos using cats as the main characters.

As in fudo myo-o, Japanese tattoos are deeply linked with stories and mental states, so people tend to think that they are difficult to understand. Horitomo thought that by having people look at cats with tattoos, similar to traditional Japanese design, he could make them more approachable. As with his first book Immovable, Monmon Cats was well-received, too. Since he published the book, he has received orders to do “cat tattoos.” He also says that he has seen tattoos with the designs from his book done by other tattooists and similar designs of tattoos on people.

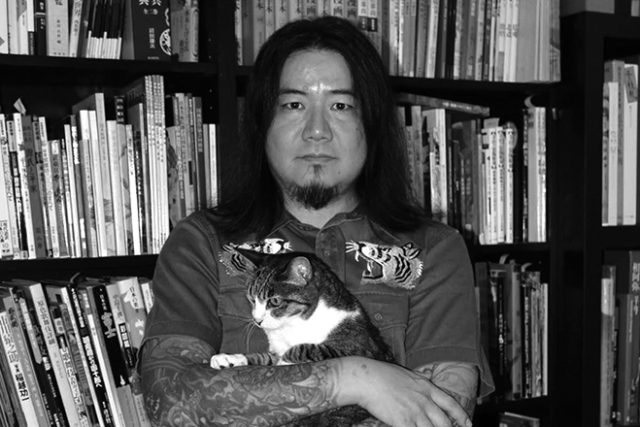

He has published two books so far. When he writes, he spends a great amount of time checking and finding resources in other books about tattoos. Horitomo has a big library, and one of the rooms in his apartment, located in the suburbs of San Jose, is full of book shelves. It looks like a “tattoo library,” and he has all the resources that he needs.

In addition to publishing books, Horitomo says that it’s also important to spread awareness of Japanese tattoos through public events.

Today we can find events about Japanese tattoos at art museums and museums in many parts of America. “I do tattoos, but I want to actively take part in such events and help spread Japanese tattoos in America,” says Horitomo.

He knows that English skills are important, too. “The vocabulary we use to talk about tattoos is limited. If we could tell stories that would reach a deeper level in people’s hearts, it would deepen their understanding of Japanese tattoos, making it true and real,” he says.

He touched on Japanese society, the one that raised him. In the beginning, Horitomo said that cats and tattoos have things in common in terms of how they are treated in Japanese society. He hopes that Japanese society would be more accepting of tattoos, as there are more and more people embracing cats as pets these days.

“If I ever go back to Japan, after retirement, for instance, I want to see people with tattoos in short sleeves on the street and in hot springs, just like in San Jose—though it might not be possible. Still, people say that pressure from the outside can change Japan, so I’m hoping that someday Japan will have another look at tattoos as the world accepts Japanese tattoos more and recognizes their value. So I think that it’s important to keep working on spreading them overseas at events about tattoos and such.”

His calico cat, who contributed to Horitomo’s writing of Monmon Cats, passed away last year. As a busy tattooist in San Jose, with his Japanese wife and an old silver tabby he picked up on the street when he was living in Osaka, Horitomo sends his expectations to Japan.

Editor’s note: This is the last part of the article, which was originally published in Discover Nikkei at www.discovernikkei.org managed by the Japanese American National Museum. The writer is a Los Angeles-based journalist and is a former editor of the Rafu Shimpo Japanese section.