by Janis Hirohama, For the North American Post

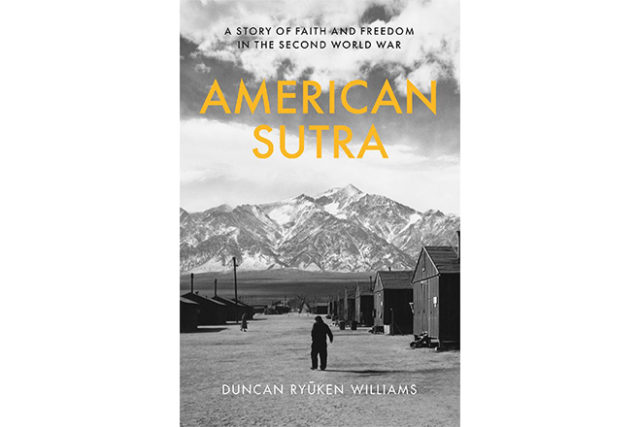

What does it mean to be an American? What does it mean to be a Buddhist? During World War II , Japanese American Buddhists were confronted with those questions under the most difficult of circumstances. In his new book American Sutra, Duncan Ryūken Williams describes how war, racism, and unimaginable hardship challenged their identities both as Americans and as Buddhists. He shows how this adversity strengthened their faith, led them to assert their right to define themselves as equally Buddhist and American, and created a truly American form of Buddhism.

Many books have been written about Japanese Americans during WWII, but American Sutra is the first to focus specifically on the experiences of Buddhists. Duncan Williams brings this neglected history vividly to life, weaving together documents, interviews, and

first-hand accounts into a compelling story of courage, resilience, and faith.

The entire Japanese American community suffered during the war, but as American Sutra shows, Buddhists were particularly targeted. U.S. government and military authorities viewed Buddhism as un-American and its followers as more likely to be disloyal. Most Buddhist priests were swiftly arrested and detained after Pearl Harbor, and severe restrictions were placed on the practice of Buddhism in both Hawaii and the mainland. Later, the forced removal and incarceration of 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast uprooted Buddhists from their sanghas and temples. In the camps they struggled to practice their faith while deprived of most of their clergy and burdened by policies that

discriminated against Buddhists.

Still, whether incarcerated behind barbed wire, living under martial law in Hawaii, or serving in the U.S. military, Japanese American Buddhists persevered and found ways to practice their religion. Prisoners at the Ft. Lincoln, ND internment camp celebrated Hanamatsuri by pouring sweetened coffee over a baby Buddha statue carved from a carrot. Young American-born Buddhists became leaders in the camps, with YBAs organizing social activities and religious gatherings that helped revitalize their sanghas.

Innovations such as gatha-singing, English service books, Sunday schools, and standardized service formats took root – elements used in BCA temples today. By fighting

for the right to practice their religion despite many obstacles, and finding new, “Americanized” ways to do so, they unapologetically defined themselves as both American and Buddhist.

American Sutra also describes how the Buddhist teachings sustained people through their suffering, and how their hardships deepened their understanding of the Dharma. As Williams says, “Imprisonment became an opportunity to discover freedom – a liberation that the Buddha himself attained only after embarking on a spiritual journey filled with many obstacles and hardships.” Japanese American Buddhists could similarly envision their ordeals as the muddy water out of which the lotus flower of enlightenment could eventually emerge.

American Sutra is essential reading. It preserves and shares precious stories that might otherwise be lost. It shows us how much we owe to our forebears who kept Buddhism alive in America in the face of incredible challenges. And it reminds us that it is our responsibility to carry this legacy forward into the future.

Learn more at: americansutra.com