By Geraldine Shu

For the North American Post

Many of us are well aware of the high regard in which the Japanese community holds Rev. Emery Andrews, thanks to his tireless efforts to provide assistance during the World War II incarceration.

What is less known is how his son had to learn from and forgive both his father and the community for precluding the father-son relationship that he so desperately needed. In his new book, “Balancing on Barbed Wire,” Rev. E. Brooks Andrews shares this well-known story from the viewpoint of the PK (preacher’s kid).

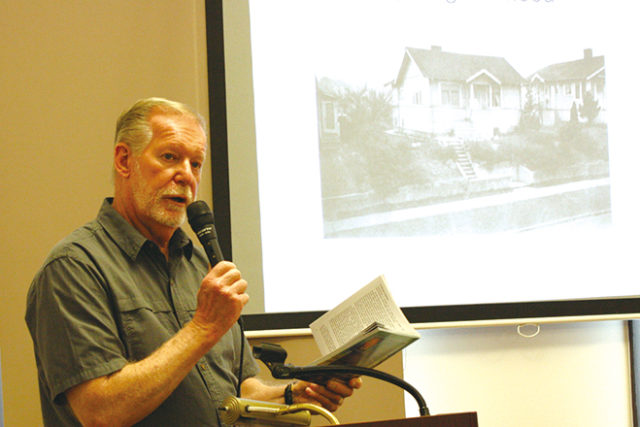

As part of the Omoide Speaker Series, Brooks read excerpts and showed many of the photos from his book to a very receptive audience at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington last Saturday.

One slide depicted him as a young, blond boy smiling alongside Nisei (second generation Japanese American) children as he explained that he did not realize back then that he was not Japanese. Other scenes and descriptions included his father and mother, the Japanese Baptist Church and the Minidoka incarceration camp. “The Blue Box,” the family bus, made 56 round trips from Seattle to Idaho, bringing supplies and personal items to the Minidoka internees.

A letter from Shigeko Uno reads, “I’ve asked you so much, I feel ashamed!” The Andrews family moved to Twin Falls, ID, for the duration of the incarceration so their home was often a popular destination for internees with day trip passes.

But, the pressing needs of the Japanese came at the expense of the Andrews family, becoming “the other woman” in the marriage and the barrier to a solid father-son relationship.

In 1989, in his early 50’s, Brooks first returned to Minidoka and began to realize its emotional impact on his life. Later on, as part of counseling training at seminary in 2003, he was required to write. It was at this time that he acknowledged his suppressed anger toward his father and the Japanese community.

This triggered a major depression, which he had to work through in order to heal himself. As a member of the Omoide (memories) writing group, he was further encouraged to express himself on paper. He revealed that the toughest thing about writing is showing up every day even if he did not write anything.

“Balancing on Barbed Wire” is the first in a series of three books. The second is due out in August and the third, before Christmas of this year. Books are available for purchase online at www.balancingonbarbedwire.com as well as from Amazon.com.