by David Yamaguchi,

OFTEN, this column shares a page with the local Japanese-American comic strip, “Seattle Tomodachi.” Accordingly, I am one of the few people who see it before it appears in print. It is the first thing I read when reviewing a proof of the page layout.

Such reading, of course, is pure procrastination. I am prolonging for a minute the editing I need to do. At such times, I believe that Buddhism—whose first tenet is that life involves suffering—is on the right track. For to edit alone in the dark of night, under deadline no less, is true human despair.

“Ack! Did I write that?”

“Will Misa (she of the ‘I need it tomorrow’ variety) let me fix it at this late hour?”

All of this is a roundabout way of saying that the relationship between Seattle Tomodachi and me is one of fondness. For in my hour of need, its amusing dog keeps me going.

One cannot read Seattle Tomodachi in this way, however, issue after issue, without starting to wonder who Sam Goto, the artist behind the comic, is.

Oh, we had met in person all right, at a talk we both attended at the Japanese Cultural Center. At the time, however, I remembered Sam being a man of few words.

And so in mid-October, when his wife Dee emailed that she wanted to meet to puzzle out how to organize a large writing project she is struggling with, I saw my opportunity. For she mentioned that Sam wanted to talk as well.

I had three questions. Who is Sam, the person behind the comic? What is his process? And how does he submit Seattle Tomodachi to the paper?

To begin, both Sam and Dee are Sansei—third-generation JAs like me. “We are old Sanseis,” they said. That says a lot, for as readers of this paper know, each generation has its own characteristics.

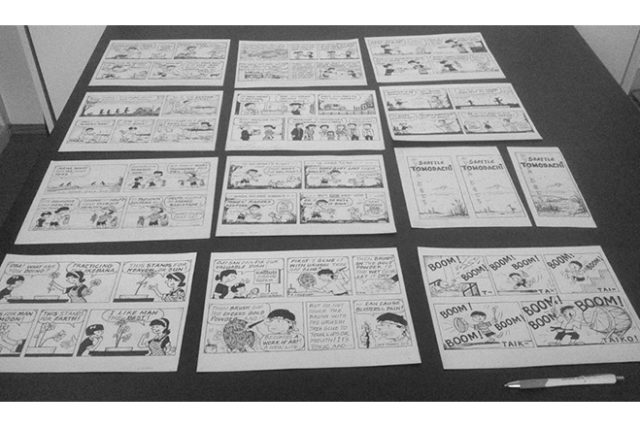

After chatting with Dee and Sam in their kitchen, I got to enter Sam’s basement man-cave, where he pursues his craft. And there, on a side table, were a half-dozen Seattle Tomodachi ready to go.

“I try to keep the table full,” Sam explained. “When it starts to get low, as it did when the grandkids were here in the summer, I start to worry.”

He gave me his illustrated book, “My Fifty Years in the Medical-Dental Building,” which I brought home and devoured in a single night. For his career, Sam made teeth as a dental lab technician.

Curiosity prompted me to check the book’s status in the only place that seems to matter these days. Yes, it is a “real book:” it is for sale at Amazon.

Where does Sam’s art come from? As he drew on the side during his working career, it seems that drawing served Sam as a creative outlet to offset a repetitive day job that essentially involved being a small-scale sculptor.

How does Sam get Seattle Tomodachi to the paper? Dee submits it as a scan. In her home office, she has a commercial-sized scanner.

What does Sam struggle with?

It is not the ideas, he says. “It is making it funny.”

“That is why I have the dog.”

Editor’s Note

The North American Post would like to express deep condolence for the loss of Sam Goto. Fortunately, he left over ten new comic strips for us and we will be able to enjoy his Seattle Tomodachi series by the end of 2018. The North American Post and Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington (JCCCW) will collaborately publish a special issue in early March, which will entirely feature Sam’s comic strips and interviews with him.