By Kenji Onishi

By the early 1900s, when the railroads were racing to lay tracks to connect the East to the West Coast, it was common practice to house laborers in boxcars filled with bunks.

After the track-laying days were finished, track maintenance workers were housed in boxcars, remodeled for the longer term. Windows and a door were added, stoves and sinks too, and the cars were set on the ground.

When father was hired as foreman in the Spokane Portland and Seattle (SP&S) railroad yard, Portland, he and his crew were provided housing in five or six boxcars. The workers, mostly single men, slept in bunks.

We lived in one of the family boxcar units. Part of one car was used as a dining area for the crew. Mother was hired to cook for the men. A Japanese style bath (furo) was built nearby.

We moved into the foreman’s “house” equipped with a kitchen stove, a sink and counter, and a dining table with chairs. At the farthest end of the car was space for a bed.

As our family grew from one child to five, Father extended the side wall to allow for a second bed. My three sisters (Masako born in 1921, Miyako, 1923, and Fumi, 1925) slept in one bed. Father, Mother and the boys (me, 1927, and Hiroshi, 1929) slept in the other.

There were no “queen” or “king” size beds in the 1920s. Breakfast conversations often began with “who kicked who” or “who took the most blankets.”

During work hours, there was a constant movement of trains just 20 feet from our front door and 30 feet in back of our house. We were often cautioned by the brakeman or engineers to be on the alert.

Our house had no electricity—only cold running water. A chamber pot was our toilet. An icebox kept food cold. Railroad lanterns gave us light.

A floor-model record player entertained us. One record was always on the turntable: “Red River Valley.” When the 78 RPM slowed to 40, 30, then 20, one of us ran to crank the turntable back up to speed.

To keep the icebox cold, we walked along the track to scrounge for chunks of ice left on the ground near the refrigerator cars.

Father had a vegetable garden in the back of our boxcar home. He grew carrots, tomatoes, potatoes, cucumbers, and lettuce in specially-built raised boxes. There was a trellis with grapevines.

In the early 1930s, the railroad yard had many transients wandering through, asking for produce from Father’s garden and sandwiches from Mother’s kitchen. At night, we had “raiders” of the family’s fuel box or faces looking in the window.

After about three years, the railroad boxcars were officially declared “uninhabitable” for family use and we were forced to move.

Atkinson Grade School, in east Portland, where I attended grades one to four, was 98% Asian. My schoolmates came from Portland’s Japan-Chinatown.

My perception was that they all came from homes with electricity, running hot water, steam heat, sidewalks, and paved streets and alleyways, where they played “cops and robbers” with neighborhood friends.

So different from my neighborhood of red cinder and crushed rocks.

Did I have an inferiority complex?

Fortunately, no classmates ever came over to play at my house.

Kenji Onishi is a former longtime Omoide participant, now retired (but strongly urged to rejoin by his writing companions). He is a retired Seattle-area elementary school teacher. Kenji is a US Army veteran who served as a weather observer in Panama.

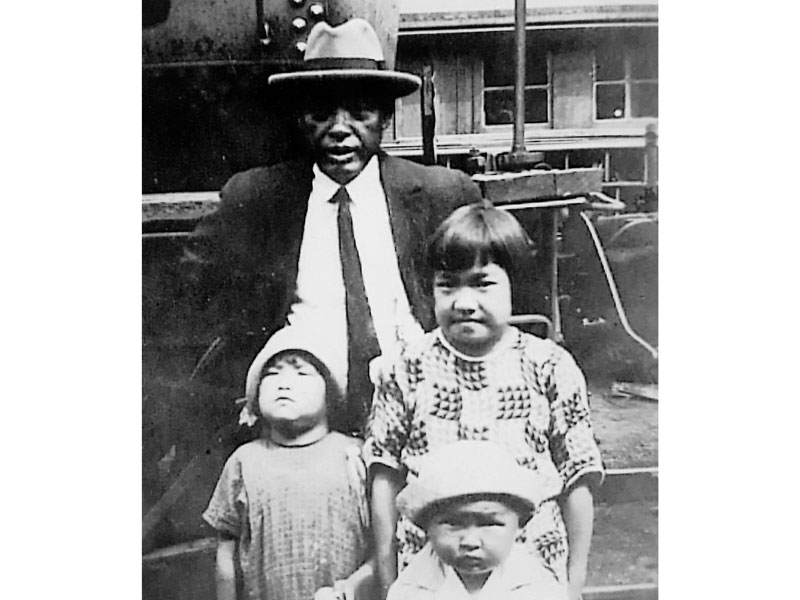

Editor’s notes: Two related online NAP stories help place Mr. Onishi’s story in context of the similar work done by Issei railroad workers in western Washington (Sansei Journal, “Issei Laborers” and “Lumbering Issei,” both Nov. 2016). The former features a parallel photo of a young Nisei boy, surrounded by Issei workers. It did not occur to me then that such railroad-car children still walk among us!

Much more on the SP&S Railway (1905-1970) is on the web. The Omoide writing program is described on the jcccw.org website under “Programs, Nikkei Horizons.”