By Rachel Gallaher

NAP Contributor

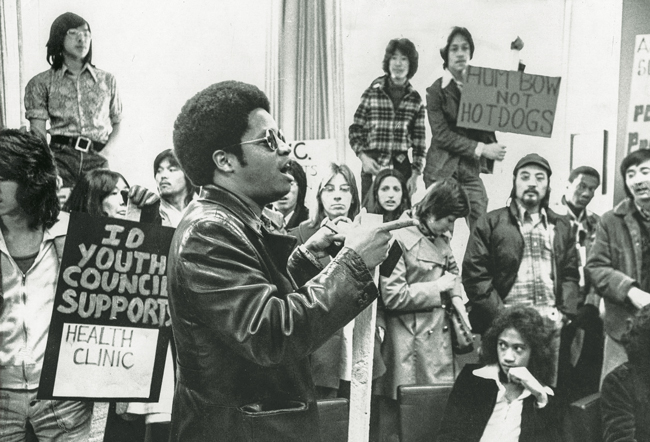

Larry Gossett addresses about 150 demonstrators at King Co. Exec. John Spellman’s Seattle office in 1975. He expressed concern about the stadium’s impact on the CID. Photo credit: Tom Brownell.

On November 2, 1972, after a steady overnight rain cleared, to leave a construction site near the King Street Station thick with mud, about 200 people gathered for the official groundbreaking of the Kingdome. A project that had seen its funding rejected several times by voters, the Kingdome was finally on its way, with the hopes that a professional football franchise would soon follow. (The Seahawks first took to the field four years later.) Amidst the initial hoopla of shovel-striking, speeches, and singing of the national anthem, a small group of protestors, mostly young Asian Americans with ties to Chinatown-International District (CID), spoke out against the forthcoming stadium.

“When the proposal came to build the Kingdome, the neighborhood had a strong reaction,” says Jared Jonson, the co-executive director of the Seattle Chinatown International District Preservation and Development Authority (SCIDpda). The organization, founded in 1975 as a city-chartered community development agency, partly in reaction to growing concerns about the economic and social future of the district, is currently celebrating its 50th anniversary with events throughout the year.

“Community leaders, business and property owners, and residents expressed deep concern about the long-term impacts of the stadium, and other large-scale construction projects proposed at the time,” Jonson explains. This included possible displacement of low-income residents, rising property taxes, increased traffic, reduced access to parking, and the long-term erosion of the neighborhood’s cultural and historic character. In some ways, the situation rang like déjà vu. In the 1960s, when the neighborhood was sliced in half due to the disruptive construction of the Interstate-5 freeway, dozens of blocks disappeared, and many businesses and residents were forced to leave their long time homes.

“It was a time of urban renewal,” says SCIDpda co-executive director Jamie Lee. “The perfect storm of things was happening, and we needed an organization to steward the Chinatown- International District.”

“This was post–Civil Rights movement,” adds Jonson. “Our neighborhood and community were asking for access to housing, jobs, better education, and healthcare. At the time, a lot of nonprofit organizations were replacing the protests of the 1960s. The identity of how we were formed ties into that community-led organization and advocacy work.”

Although the Kingdome protestors failed to stop the construction of the stadium, they helped kick off a movement that led to the formation of SCIDpda. It would become a powerful force in the preservation and uplift the CID by focusing on three specific areas: real estate development, property management (primarily mixed-use buildings with affordable housing), and community development and engagement. This includes senior services and the formation of the IDEA Space. It was rebranded in 2018 as Community Initiatives which focuses on public realm improvements, small business support, and community advocacy around large-scale events like the upcoming 2026 Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) WorldCup™.

“SCIDpda has 13 properties that we own or manage which equates to 559 units of affordable housing,” says Jonson, noting that the Bush Hotel in Seattle was the first property the organization purchased in 1978. Most residential tenants earn at or below 30 percent of the area median income. It makes SCIDpda’s effort to provide and retain affordable housing a vital resource for the neighborhood. The properties also support commercial and civic spaces such as restaurants, shops, a health clinic, a public library branch, and a community center.

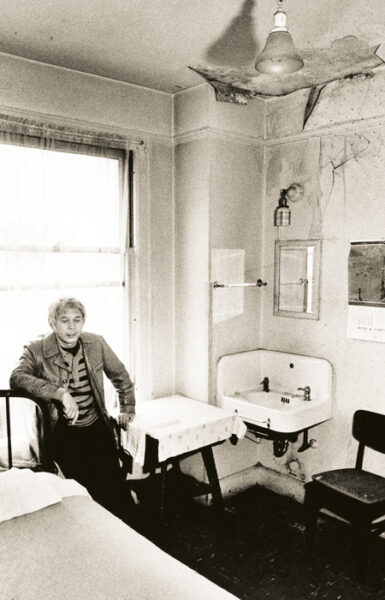

Bob Santos (1934–2016) sits in a sub-standard hotel room apartment. He spent most of his life as an activist of his old neighborhood. 1989-93, Santos oversaw the SCIDpda. Photo courtesy: Museum of History & Industry.

The organization’s goal with property management is to support independent and family-owned businesses, and crucially, help them stay in the community. Of the 13 properties SCIDpda manages, five are owned by local families. As a nonprofit organization, SCIDpda also benefits from the management fees, which go towards covering their operating costs.

“We have 53 employees,” Jonson says. “Half of them is in operations — janitors, building managers, etc. and half are limited in English proficiency. We like to hire from the neighborhood, and we have a range from older Chinese guys to our younger Gen Z staff.”

“We’re not going anywhere despite what you hear on the news.The neighborhood is not dying. Anyone can come down here and see that it’s very much thriving.”

This mix reflects the diversity of the area which is home to many inter-generational families – a much hoped for focus of future housing projects. Rather than following the one and two bedroom trend seen elsewhere in the city, Jonson and Lee aim to bring the area additional housing that reflects its social and cultural needs. Apartments with three or four bedrooms that can accommodate families where parents, children, and grandchildren live under the same roof, is a common household structure for many cultures around the world. The first project of this type in the neighborhood, International District Village Square II, was built in 2004.

Currently, SCIDpda is involved in the Little Saigon Landmark Project — a co-development with Friends of Little Saigon (FLS) slated for a piece of land at South Jackson Street and 10th Avenue South. Although still in the design and permitting phase, the plans include a Vietnamese Culture and Economic Center (managed by FLS), affordable housing, commercial space, offices, and community meeting areas. Like much of SCIDpda’s work, it is a positive light pointed towards a prosperous and more equitable future. It is proof that the neighborhood continues to rise above the onslaught of negative news coverage that has plagued it in recent years. According to Lee, SCIDpda is choosing to focus on the positive, like the 35 new businesses that have opened since 2023.

“We’re not going anywhere despite what you hear on the news,” says Jonson. “The neighborhood is not dying. Anyone can come down here and see that it’s very much thriving.”

This upward trajectory would not have been possible without the hard work, dedication, and unwavering support from SCIDpda over the past five decades. To mark the milestone, the organization hosted a series of guided neighborhood tours throughout the year, each based on a different period and topic. In November, the SCIDpda 50th Anniversary Gala celebrated the many triumphs of the organization, while raising money to help it continue to push the CID towards its next decade and beyond.

“What I want in the next 50 years, is for the neighborhood not to look exactly the same but to have the same feeling,” says Lee. “People arguing over table tennis and older ladies playing mahjong in the park — if that’s still happening, that’s where we’ll know we have been successful.”

(To read the original article, go to: seattlemag.com.)