By Larry Matsuda, Ph.D.

NAP Contributor

Dear Editor,

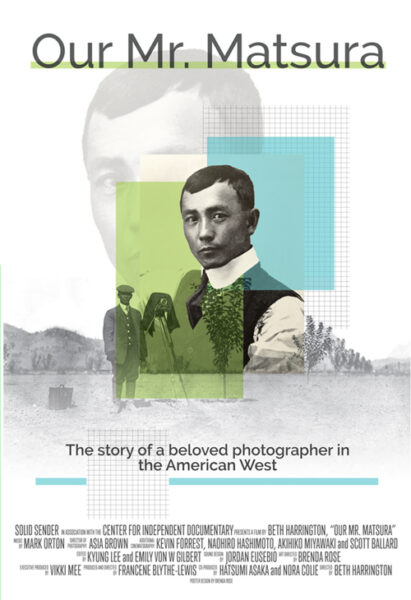

It was with interest that I read the short piece on Frank Matsura by Beth Harrington in the August 22, 2025 North American Post. She is a co-producer and director of the documentary video, Our Mr. Matsura.

About two years ago, I had a discussion with Harrington about the film. Frank Matsura came to eastern Washington in the early 1900s from Japan and became a noted landscape and portrait studio photographer. Photographs exist of him dressed as a native American, and his landscapes of the Okanogan country are well known.

I pointed out to Harrington that the title was in poor taste and distracting. The “Our” reference was patronizing and indicated a sense of possession-like property. It is reminiscent of the phrases, “Our dog Spot” or “Our slaves are happily singing in the fields.” Harrington responded that the Japanese co-producer from Japan thought the “Our” was okay. That response is an excuse and not an answer.

Nevertheless, why is the “our” necessary and who does it refer to? More than likely, it refers to white people looking back on history and interpreting it from their modern viewpoint. Their bestowing the “our” on Frank Matsura indicates that they thought he was not like the other minorities at the time.

The “our” almost canonizes him posthumously as an equal. In reality, that elevated status would be tested, if Frank dated a white woman and went over to her house for dinner and met her parents. So, for some he was “beloved” but to strangers he was just another low status Asian.

Ironically, if Frank Matsura were alive in 1942 and living on the west coast, he would have ended up in an American incarceration camp because he was Japanese. The American government would not have seen him as “our” talented and beloved person. His photographic equipment would have been confiscated and probably much of his work destroyed. So much for “our” Mr. Matsura.

The title is truly a self-inflicted wound and missed opportunity. If Harrington simply called the video, “Mr. Matsura” or “The Beloved Mr. Matsura,” we would not be distracted by the implications of the current title. Instead, we could focus on the real genius of Matsura’s work and story.

By Beth Harrington

NAP Contributor

I would like to thank The North American Post for this opportunity to respond to Dr. Lawrence Matsuda’s letter regarding the title of our film.

Dr. Matsuda is an honored person in the community, and he certainly has a right to his opinion. Once he sees the film, I hope he will understand the intention of all of us who worked on it.

The title Our Mr. Matsura is meant to convey connection and affection for this uniquely talented Japanese photographer who built community at a fraught time in the Okanogan region of Washington State. Through his art, kindness, humor, intelligence and charismatic personality, Frank Matsura cultivated friendships with homesteaders, other immigrants and, especially, the people of the Colville Confederated Tribes and amplified their shared humanity. These relationships between Matsura and the people in the Okanogan created a profound legacy that endures today in the way local people still know and appreciate Matsura and his work. Their bond to him, then and now, is one meaning of the “our.”

Another meaning is that because we are still trying to learn more about who Matsura was, the present-day conjecture about him and his work means that each person who explores his life comes up with another idea of him. All those personal impressions form another sense of “our”: “Here is the man who lived among us and here is my little understanding of who he was.” These impressions add up to a collective portrait of him – “our” Mr. Matsura, the man who created a portrait of them as a community. These are the underlying themes and, in fact, structure of the film.

In April, we held two free community screenings of the film in the Okanogan of Washington, filling the 300-seat theater there twice. Notably, many of the descendants of the people whom Matsura depicted, people who participated in the film, were in attendance. Several people from the area commented on how the film had brought people together in the same room who do not often share those spaces. It was striking to everyone.Tribal elder Randy Lewis said it best, “Frank Matsura has done it again. He’s bridged the communities and brought us all back together again and that’s the way it should be.” That is the “our” intended in the title.

I hope when the film is eventually screened in Seattle that people from the community will come to celebrate this unsung but powerful artist. My intention, and that of the entire team, has always been to honor him and create visibility for his remarkable life and outstanding work.