By Elaine Ikoma Ko, Special to The North American Post

Photos by Matsuda family (unless otherwise noted)

Larry Matsuda, higher education Ph.D. Racial/social justice activist leader. Accomplished educator. Award-winning author, poet, and more. This author was intrigued to explore what is so unique about Dr. Larry to have accomplished so much and in such diverse arenas. This interview, like last issue’s, seeks to capture key experiences that molded Dr. Larry’s life: being born in an incarceration camp during World War II, post-incarceration family trauma growing up, and what drove his indefatigable efforts to bust through many barriers in the 1960’s and beyond. He was more than prescient in the ’60s to understand the importance of multi-racial and Pan-Asian unity, still relevant today.

These days, Dr. Larry continues to “do” and not just “observe.” In his seventh decade of life, he is as engaged as he was in his 20’s. We look forward to, with anticipation, his noteworthy contributions still to come.

Editor’s note: The first interview of this two-part series is in the March 12 issue.

Larry Matsuda, PhD, aka “Dr. Larry,” was born in the Minidoka incarceration camp during World War II. As a Sansei, he grew up in the diverse central and south Seattle neighborhoods. He is an accomplished author, poet, educator, and social justice activist.

www.lawrencematsuda.com

What raised your consciousness about the incarceration camps and tell us about your involvement in developing the “Pride and Shame” exhibit during the 1970’s.

As a child, I remember saying the Pledge of Allegiance. I mouthed the words and did not say them out loud because I knew they did not apply to me.

The Civil Rights Movement of the ’60s and reading “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” (1965) motivated me to move from “thinking about history” to “taking action.” As a teacher at Sharples Junior High, I started the first Asian-American history class in 1969. In 1970, I team-taught an Asian-American history course at Seattle Community College with another educator, Bruce Dong.

Around the same time, local leaders Tomio Moriguchi and Min Masuda were putting together a Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) exhibit for the Museum of History and Industry, Seattle. The museum staff thought they were getting a Japanese cultural exhibit. But Tomio and Min had an entirely different idea and invited me to participate because they wanted to focus on the Japanese American forced incarceration.

I suggested the exhibit name, “Pride and the Shame,” and much to my surprise, Tomio and Min accepted it.

My Asian-American history class students contributed a camp barracks and guard tower model for the display. Later, the “Pride and the Shame” panels became a traveling exhibit. According to Bob Shimabukuro’s book, “Born in Seattle” (2001), the exhibit was the impetus for the national reparation movement, seeking government formal apology and monetary retributions, started by the Seattle JACL.

So, I can make a small claim regarding the success of reparations.

There is a saying: “Success has a thousand mothers and fathers and failure is an orphan.”

What other contributions have you made to racial justice for Japanese Americans wrongly incarcerated?

When I was a visiting professor at Seattle University, some of the administrators were approached by Yosh Nakagawa about making a Japanese-American Remembrance Garden. Before the war, Japanese lived on what is now south campus. The university asked me to chair the fundraising and design process. When I declined, they asked that I become a co-chair. I agreed, but soon found that I was a co-chair of one.

Nevertheless, I headed up the project and we raised the funds quickly. Al Kubota, grandson of Fujitaro Kubota, who designed nine garden features on campus, built the tenth garden. Currently, a commemorative plaque and garden now stand near the Chapel of St. Ignatius and School of Theology and Ministry. Each year the garden is used by Japanese-American religious groups for Easter services.

In 2017, I worked with artist Roger Shimomura to open a year-long exhibit featuring his art and my poetry at the Wing Luke Asian Museum entitled “Forever Foreigner.” The exhibit commemorated the “Day of Remembrance,” regarding the signing of Executive Order 9066, which incarcerated Japanese Americans during WWII.

You have given hundreds of presentations/lectures and published books. What has been your most cherished subject that you feel had perhaps the most impact on audiences?

Telling my story about the forced incarceration made me realize that it is not a monolithic experience. Many experiences are similar but realistically there are at least 120,000 different stories and each is unique.

Some people were in denial, others angry, some were depressed, and others used it as a motivator to become 110% Americans.

Once, during a presentation at the Minidoka Pilgrimage in Idaho, I read my poem, “The Noble Thing.” Many in the audience cried. Later, one former incarceree said she had never cried for Minidoka “until today.” Another person said that he was raped as a child and “the forced incarceration was like a rape of a community based on race.”

I’m also proud of my graphic novel, “Fighting for America Nisei Soldiers.” Chapter One, entitled “An American Hero, Shiro Kashino,” was animated by the Seattle Channel and it won a 2015 regional Emmy award.

When did you start writing poetry — and what is the creative process that you use? Do you start with a thought or theme, or do you just start writing with spontaneous ideas?

When I was about seven, I wrote a poem for a contest at Safeway about Skylark bread.

It was “Skylark is the bread for me because it gives me energy. Other breads they say are fine, but they aren’t worth a dime.”

I thought it would win. Naturally, I was disappointed when the contest ended and I got nothing.

Since then, I wrote more bad poetry until I got my Ph.D. and took a class from Professor Nelson Bentley at the University of Washington (UW). After the class, my poems were better, but still mediocre with flashes of goodness.

In about 2005, I decided to write quality poems, began my manuscript, “A Cold Wind from Idaho,” and worked with professional editors. My artist friend, Alfredo Arreguin, invited poet Tess Gallagher to look at my manuscript. She liked it and helped me for over a year to finalize it. She stressed the importance of including emotional content. In 2010, Black Lawrence Press, New York, published it.

Underlying many of the poems is anger. Usually, Japanese rarely speak about their incarceration and when they do, they focus on the bad living conditions, food, and loss of property. Rarely do they discuss the emotions—anger and sense of betrayal. I go straight to those emotions in my poems.

Elizabeth Kubler Ross’s stages of accepting death include anger, denial, negotiation, depression, and acceptance. In terms of the forced incarceration, I will never reach acceptance nor denial but remain somewhere between anger and depression. So, my writing reflects those features and resonates best with people not in denial nor acceptance about the forced incarceration.

I also realize that you can’t please everyone. Instead, I try to please myself, which entails mounds of revisions and changes.

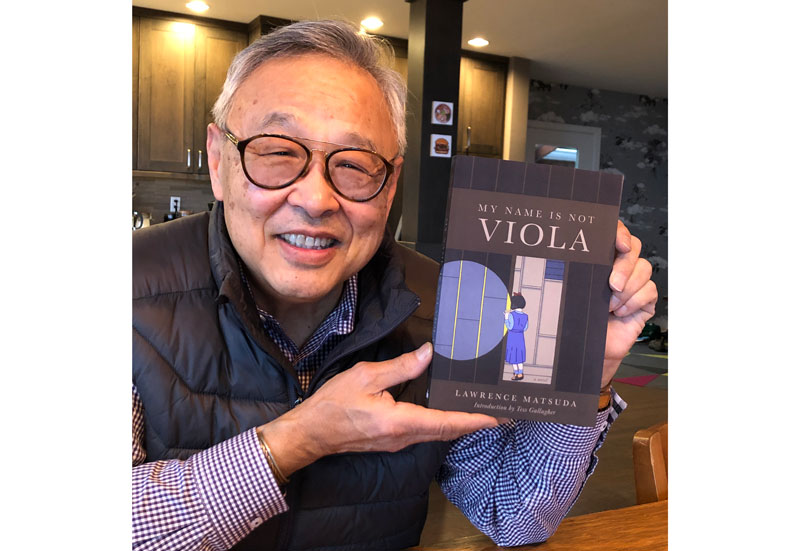

For example, my first novel, “My Name is Not Viola,” started as a play. It is based on my mother’s life—she was born in Seattle, sent to Hiroshima for an education, returned and got married, was sent to camp, was incarcerated again in a hospital for depression, and finally returned to normal life. I knew it was a good story but my challenge was to make a play into a good novel which took years of revisions.

Often, people ask “Can you ever get over this (forced incarceration)?” Or, “Is it cathartic to write about it?”

And, the answer is NO. There are some betrayals that cannot be forgiven nor forgotten. Damage was done and I just live with it.

While I have written many serious poems, I also enjoy writing humorous nonsense poems.

One was published by Raven Chronicles. It should be read out loud with gusto. I invented cartoon characters to say crazy words and phrases that I collected. The title is “Sheriff Abadaba and Deputy Fluff.”

“Cucamonga, there’s a brouhaha in the Chimichonga Tavern, Abadaba.

Cut the hoopla, Fluff, and hand me my bazooka. Let’s go to the:

Congo Room, Congo Room, Chimichonga Congo Room

Gigolo Gumbo Kumquat, miniature King Kong, squeezes Porgy Doormouse. Kewpie doll, shrieks Porgy.

Vertigo, Where’d he go? Vertigo, Where’d he go? Vertigo

Ding dong, drop your long johns, Gigolo. We’re puttin’ the patchwork panacea on you, shouts the Sheriff.

Humbug, Abadaba. You and that flea flickin’ Fluff can take this Doormouse and shove him up your:

Congo Room, Congo Room, Chimichonga Congo Room”

You were instrumental in the recent naming of Alan Sugiyama Way, on Seattle’s Beacon Hill. Why was this project so significant, especially to people who don’t know why we should honor him?

Al graduated from Garfield High School and lived on Beacon Hill. He started the Center for Career Alternatives which implemented job training for disadvantaged people in Seattle and Everett. Also, he was the first Asian-American Seattle School Board member and served two terms.

Twenty-six years ago, as the President-Elect of the UW Alumni Association, Vivian Lee and I started the Multicultural Alumni Partnership (MAP) which sponsored a homecoming breakfast. We gave student scholarships and Alumni recognition awards to community people who contributed to social justice. Al was one of the first MAP distinguished Alumni awardees.

When Al passed away from cancer in 2017, Willon Lew and I submitted an application to the City to name a street in honor of Al.

For years, Beacon Hill has had a large Asian population, but it is becoming more gentrified. We thought it would be very important to recognize Al as an Asian-American resident before the neighborhood changed completely.

The project was supported by City Council President Bruce Harrell and it passed unanimously. The street signs were especially important since they were near Al’s home. To this day, his daughters drive by the signs on their way to work.

You have said that you will never “retire.” What are you focused on these days — and what keeps you moving?

I like to quote Churchill: “Success consists of going from failure to failure without the loss of enthusiasm.”

I always have goals—I want to catch more king salmon on the Columbia and visit Paris again. Years ago, at the Chartres Cathedral in France, I walked up the 900-year-old stone steps and felt that I had been there in another life. So, I want to go back.

Also, I want to win the grand prize of a lottery and hope that my novel becomes a movie.

Last year, our MAP scholarship endowment passed one million dollars which means that the scholarships are funded in perpetuity. I’d want to see us reach two million.

These are some of the things that keep me moving.

When I was a Cornish College of the Arts trustee, Lauren Iida, a young art student, approached me and asked if I could arrange a meeting with artist Roger Shimomura. I hosted a lunch where they met and discussed art. Since then, I have helped her with art dealer contacts, ideas, and projects.

Currently, Lauren is in Cambodia and runs an art collective (www.openstudiocambodia.com). One of her young artists has no hands and another has one arm as the result of factory accidents. Both have been highly successful under her tutelage and make a good living selling their art internationally.

Lauren and I are working on several joint ventures including a large public art mural in Bellevue set to open this fall or winter.

In addition, I have a group of critical friends who help me—Tess Gallagher (famous poet), Roger Shimomura (famous artist), Alfredo Arreguin (famous artist), Jay Rubin (translator for author Haruki Murakami), and my wife, Karen. They improve my written work and freely give advice and suggestions. Because most are famous, my ego is always in check.

So, if there is a message I want to convey, if my story resonates with anyone, it would be: “Find a cause and become a force for change.”

It could be participating in a march, taking the lead on some venture, or contributing to a worthy cause. And if you find like-minded people, you can join together and become a force of nature.

Finally, I would like to be remembered as someone who did more good than harm as an advocate for social justice and change. But more than anything I hope that my work has touched people’s hearts and minds to the point that they are motivated to take action and become a force for good.

To quote Churchill again, “Success is not final. Failure is not final. It is the courage to continue that counts.”

(Reader warning: this poem includes harsh descriptions)

“The Noble Thing”

“Dad never talked about Minidoka.

That was the noble thing.

Before World War II,

there was Garfield High School for him,

ice skating on Greenlake,

dances at Lake Wilderness Lodge,

later his ownership of Elk Grocery

on Seneca Street.

He and my mother were

married in 1941,

ten months later to be removed… forced… into the Minidoka concentration

camp.

Mom was five months pregnant in

August

with my older brother, Alan.

With black-out curtains drawn, the train

left Puyallup and climbed the Cascade mountains until the land flattened and the inescapable sun

transformed the train cars into a moving

sauna.

People gasped small, panicked breaths

from the superheated air.

Shikataganai—“It can’t be helped.”

The train stopped by the side of an

unmarked road

in the Idaho desert, released

its passengers miles from any station.

Rumors spread they would be shot

or marched to death – their bodies

stacked, then

carted to some awaiting ditch.

Nowhere to run,

they walk in their best shoes

in the gritty sand as on the face of the

moon.

The heat caused some to faint

as they carried all they could.

Three years later, Dad returned

to Seattle after the War,

developed a bleeding ulcer,

lost his janitor job at the Earl Hotel.

Depression took Mom away

like invisible armed guards. She was

a stranger—a stick-like figure with arms and legs poking out of a white smock,

pacing the sidewalk next

to the Western State Hospital turn-

around.

Dad never talked about it, none of it.

I never heard him say the word Minidoka….

Gaman, “endure the unbearable with

dignity.”

Shikatagani, my best friend’s mother

chose pills for suicide.

After school, Randy my neighbor,

opened the garage door

and found his father in a black suit,

his best, hanged by the neck,

shikatagani, the same path other

Seattle Japanese chose—

numbers unknown. Shikataganai.

We, however, never talked about it.

That was the noble thing to do.”

From Matsuda, Lawrence, 2010, “A Cold Wind from Idaho,” Black Lawrence Press, New York, 79 pp.

Editor’s notes. “Alan Sugiyama Way,” which doesn’t appear on Google Maps, is a one-block section of 15th Avenue South that runs south from S Nevada Street to its junction with curved Columbian Way (MacPhearson’s Fruit and Produce). Two honorary street signs mark its endpoints on the west side of the street.

Min Masuda is a name not heard often anymore. Some of his story is in the book, Masuda, Minoru, 2008, “Letters from the 442nd, UW Press, 290 pp.