By David Hirata

Since the age of ten, I’ve been a magician. I spent many hours during my childhood wearing a top hat and cape, waving a wand and brandishing a deck of cards. I’ve long since abandoned those Victorian accoutrements but have continued to work sleight-of-hand amusements for audiences in hotel banquet halls, living rooms, and theaters.

As in other art forms, the world of magic looks to master practitioners of its past. The magic inventions of these past masters all carry the stamp of their individual styles—sleight-of-hand sequence with cards by Dai Vernon is elegant and natural, the ball manipulation of Geoffrey Buckingham is intricate and beautiful, and the coin sleights of David Roth are crafty and efficient.

Last year I discovered the master magician; the Japanese Namigoro Sumidagawa. In 1866, Sumidagawa became the first Japanese citizen issued a passport by the Edo Shogunate for the purpose of visiting America. He and the other members of the Imperial Japanese Troupe performed for two American presidents, and gave many thousands of Americans their first face-to-face glimpse of Japan. It thrilled me to learn that a magician was one of the first to introduce my people to the American masses.

The life of every artist is, in some way, recorded in his/her work. So, I sought to commune with the spirit of Sumidagawa by delving into his magic, by sharing in his secrets. I had already read the works of the great twentieth century Japanese master magician Tenkai Ishida, whose revolutionary sleight-of-hand techniques are still used today. Fortunately for me and my history project, Tenkai also recorded descriptions and methods of old classic Japanese magic wazuma, and I found an English translation of Hokasen, an eighteenth century book of Japanese magic that gave me a glimpse of wazuma as it may have been practiced in Sumidagawa’s lifetime.

I acquainted myself with the Owan To Tama, the Japanese equivalent of the Western “cups and balls” trick I’ve performed many times. I was surprised (and a little dismayed) to rediscover the Soko-nashi Bako, a very clever piece of wazuma which I had learned of as a teenager. Victorian Era magicians in the West had been quick to appropriate the Soko-nashi Bako, and it was quickly renamed “the Jap Box.” Clever as the trick was, I had not been anxious to associate with it. Besides, I had my eye on one particular feat.

Sumidagawa’s most famous illusion was the Ukare-no Cho, known to astonished American audiences of the time as “the Butterfly Trick”. Seldom seen today, it’s a beautiful recreation of life: a piece of tissue paper is torn into the shape of a butterfly. As the magician gently fans the paper, the butterfly seems to come to life, fluttering about the stage, drinking from a small cup of water, finally taking to the air with a large flock of butterflies. Properly performed, it is absolutely beautiful.

Ukare-no Cho is extremely difficult to perform. As I began working with the mechanics of the piece, I was struck by how much engineering was required to assemble the workings—this was not something that could be bought online in a magic kit. Descriptions of the method were sparse, leaving me to work out many details on my own.

But I was delighted to realize that this is what Sumidagawa would have had to do himself. The explanations of magic in Hokasen, while fairly well detailed and illustrated, left much up to the student. And the exacting work in assembling the props and gimmickry for the Ukare-no Cho gave me a real appreciation and awareness of the needs of the piece. Simply preparing to practice the Ukare-no Cho requires a clear mind and steady fingers. A slight change in the fold of the tissue, or in the positioning of the hands on the fan during the performance can make the difference between a magical presentation of life, and a botched craft project. I was grateful to have modern advantages Sumidagawa did not—simple things I take for granted, like scotch tape and plentiful, inexpensive tissue paper from Safeway must have saved me many hours of frustration.

At the end of his explanation of the Ukare-no Cho, Tenkai summed up the effort to master it by simply saying, “this is very difficult to explain in print. You will have to experiment and practice.” Tenkai is famous amongst magicians for his statement, “Magic is not tricks. It is a Way.” This meticulous balancing act, of executing precise, hidden mechanics in service of beauty requires not just an understanding of the secret “trick,” but a willingness to engage in the little drama created by the props and the movements.

Now, after more than a year of practicing the Ukare-no Cho, I’m nearing the level of perfection necessary to put it in front of a live audience. The tissue butterflies and the secret mechanism must be replaced often, and I marvel at the thought of Sumidagawa crafting these props “on the road,” probably with cruder tools, poorer light, and an inferior workspace to what I have.

The experience of following in Sumidagawa’s footsteps, of following the Way of wazuma, led me to revisit the Soko-nashi Bako—the “Jap Box” of my childhood—to approach it as Sumidagawa may have done. I was astonished to find that the rhythms and aesthetic I’d learned from working with Ukare-no Cho gave me a new understanding of “the Jap Box” and gave me a means to reclaim the Soko-nashi Bako.

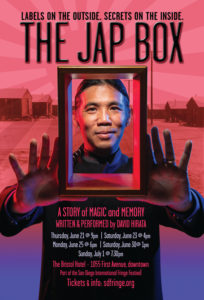

The experience of trying to walk in Sumidagawa’s shoes, of navigating the craft of the magician through the techniques of American stage magic and Japanese wazuma gave me a lot to think about my own Nikkei experience. So I began to weave the stories of Sumidagawa’s life with my own stories, and to combine Western magic with wazuma into a theatrical memoir. This past summer, I premiered this show, The Jap Box, at the San Diego International Fringe Festival, and will bring it to San Francisco in early 2019.

I still love the magic of the American, English, and German masters that forms the backbone of my repertoire. These pieces, chosen in no small part for their ease of preparation and suitability for performance under the most difficult circumstances, are the working repertoire I use most often. But there is a special joy I take now in setting aside time to work on the Ukare-no Cho, the Soko-nashi Bako and Owan To Tama in the wazuma spirit. It’s a lot of fun and the spirits of Sumidagawa, Tenkai, and the other wazuma practitioners are very good company.

[Editor’s Note] This article was originally published in Discover Nikkei at <www.discovernikkei.org>, which is managed by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

David Hirata is a magician who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. His magic storytelling show, The Jap Box premiered at the San Diego International Fringe Festival in June 2018, where it won the festival award for “Outstanding World Premiere Show.” He enjoys hikes with his family, jazz, a good serving of tsukemono, and laughing at his cats.