Nikkei-American immigration history celebrates it’s 150-year milestone this year. This history spans even across the unfortunate events of World War II. Just what was the actual state of things at that time? Let’s look back on the Nikkei history of Seattle up to now and hear from those who experienced it firsthand.

Interviews and article by Minami Hasegawa, Translation by Andrew Wexler

- Meiji Restoration Marks the Beginning of Nikkei History

- Mail Order Immigrants ~ The Emergence of Picture Brides

- The Outbreak of World War II and the Internment of Nikkei

- Yes, Yes or No, No

Nikkei Conflicted on Loyalty - Seattle’s Japantown After the War

1. Meiji Restoration Marks the Beginning of Nikkei History

Nikkei immigration history, now seeing its 150th anniversary this year, begins from the Meiji Restoration in 1868. The first Japanese laborers in Hawaii, called Gannen Mono or “First-Year People,” landed in Honolulu in Meiji Gannen, the first year of Emperor Meiji’s reign. There were approximately 150 Gannen Mono at that time. A new era began as modernization progressed throughout the country with the opening of railways and the prevalence of western style clothing and architecture. However, this modernization within the agricultural industry brought forth a labor surplus in rural farming areas, prompting young people in those villages to cross the ocean one after another with dreams of immigrating and making it big. Moreover, when the Russo-Japanese war ended in 1905, many of the returning soldiers who were out of work due to The Depression of 1920-21, traveled to America to secure a livelihood.

Here in America, due to the labor shortages plaguing both Hawaiian plantations and the advancing west coast railroad and coal industry, there was a growing demand for foreign laborers. Given such circumstances, many people left Japan without passports, nor government permission. As a result, at their destination some people would be subjected to slave-like treatment and be paid only 4 dollars a month for 10-hour working days.

In 1896, when a Nippon Yusen ship began an operation between Seattle and Yokohama, Seattle saw a rapid increase of Nikkei immigrants. Stepping off the boat into a country of a foreign language and culture, Issei (first generation Nikkei) wandered from plantation to plantation working far more than Americans. However, the diligence of the Japanese who continued working even into the weekend was at times seen as a threat to American society and even became a factor in the birth of an anti-Japanese sentiment.

Nikkei Family History 1

The Japanese Who Crossed the Ocean – Ideguchi Family History

In 1914, Miyoshi Ideguchi, great-grandfather of Seattle University Student, Sharon Ideguchi, immigrated from Kumamoto prefecture to Hawaii at the age of 15.

After losing his parents and being left with no living relatives, he came to America without hesitation in search of a new life. In Hawaii, he worked on a pineapple plantation, but the working conditions were harsh. With no established water lines, he collected water in buckets and carried it back to the plantation. A few years later, he married Tsuya, a woman who came from the same prefecture. He intended to go back to Japan after he had earned enough money; however, he could not afford to return. He thought that at the very least his wife should return to her parents’ house to let them see her as a married woman. With that sentiment, he used the money he earned by working to allow her to go to Japan several times. Since parting from Japan, Miyoshi himself never left the islands of Hawaii.

Near the end of World War II, Miyoshi’s son, Hisashi enlisted in the U.S. Armed Forces in Hawaii. To prove his loyalty to the American army, Miyoshi changed his name to Richard and ceased using Japanese, even choosing not to teach it to his own children.

Miyoshi’s family lived and worked on the Takeyama Pineapple Plantation of which was managed by a white family. Every Friday school was cancelled, and Miyoshi’s grandchildren went to the government protected “Victory Garden” to harvest vegetables such as beans and potatoes on behalf of the troops.

Read Sharon Ideguchi’s related article

https://napost.com/dragon-in-seattle-ideguchi-family-history/

2. Mail Order Immigrants ~ The Emergence of Picture Brides

1908 to 1924 was referred to as the “Picture Bride Era,” as young single men who initially immigrated would send away for spouses from their hometowns.

Anti-Japanese sentiment began to rise and as a result of the Meiji government imposing more control on immigration for migrant workers, it had become a requirement to start a family in order to immigrate legally. As a result, many Japanese women decided to marry and cross the ocean despite only making correspondence and conducting marriage interviews with their prospective husbands through photographs. These women are called Picture Brides and every year several hundred of them came to America to start a family.

It was a picture marriage system born from the mutual interest of men who wished to settle down in America and women who wanted to break free of their poor lives in Japan. But this strange culture soon became the target of criticism within American society. Furthermore, Anti-Japanese sentiment would rise even more due to the rapid increase in the population of the Nikkei community. In 1924, this picture marriage system became the motivation for banning all Asian immigration into America, with the exception of Filipinos.

3. The Outbreak of World War II and the Internment of Nikkei

Issei gradually found success in agriculture and self-owned businesses and thus were able to gain great economic prosperity. In 1930, there were as many as 8,500 Nikkei living in Seattle, making it the second largest Nikkei community in North America, following Los Angeles.

However, due to the Great Depression in 1929 and the start of The Sino-Japanese War in 1937, relations between Japan and America were starting to look progressively worse. This put the Nikkei community in a tough position, as racist attitudes against Japanese people in America escalated further. At this time, the U.S. saw an increase in people returning to Japan.

Then in 1941, when World War II broke out with the attack on Pearl Harbor, Nikkei in America would begin to be seen as the enemy. During World War II, as many as 120,000 Nikkei were sent off to one of 10 internment camps across the country. Even Nisei (second generation Nikkei), who were born in America and held American citizenship, became a target of this persecution. Nikkei immigrants, stricken with the fear and anxiety of not knowing when this would end, were forced into internment camps, having to give up their land and property that they worked so hard to attain after immigrating to America.

Nikkei Family History 2

Life in Minidoka Internment Camp, interviewing Irene Mano

“Before the war, there was much stronger racism against Asians for a long time. I couldn’t have a job and I couldn’t own land, only because I looked different from European immigrants. I could only live in a designated area like the modern day Japantown and it was too dangerous to go out after 8 pm.”

When the order for internment was issued, Irene Mano and her family were sent to Minidoka internment camp in Idaho. Each person was only allowed to bring a single suitcase to the camp.

Irene, with her luggage in tow, unknowing of where she was going or when she would be able to return, boarded a railcar and began an anxious and terrifying journey that lasted two and a half days.

The American government claimed that these internment camps were “for the purpose of protecting the Japanese-Americans from harsh racism,” but I wonder what the real reason was. “I think the fact that Nikkei were prospering too much was one of the reasons for internment. I was young at the time, so it didn’t have much of an effect on me, but for Issei like my parents, it was an atrocity. All the land and property my parents worked so hard to amass after immigrating had been confiscated. They were furious, but they endured it with no complaints. Just like a normal hard-working Japanese person.”

As a Nisei with Japanese parents, just how did Irene feel during her time in the internment camp? “I’m an American who was born and raised in America. Being interned despite this felt strange. In the camps, there’s no privacy at all. And yet, I gradually accepted reality.”

Read Minami Hasegawa’s original article in Japanese;

4. Yes, Yes or No, No

Nikkei Conflicted on Loyalty

In February of 1943, something happened that would cause the interned Nikkei to become deeply divided. A questionnaire targeted at all Nikkei over the age of 17.

It was called the “Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry,” but the content of the questions generated controversy and it also became known as the “Loyalty Questionnaire.” This was because, in addition to personal information such as name and place of birth, it also included the following questions.

27. Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?

Similar to a Fumi-e (a tablet bearing Christian images, on which Edo-period authorities forced suspected Christians to trample), a yes or no answer was requested, without them even receiving a full explanation in advance.

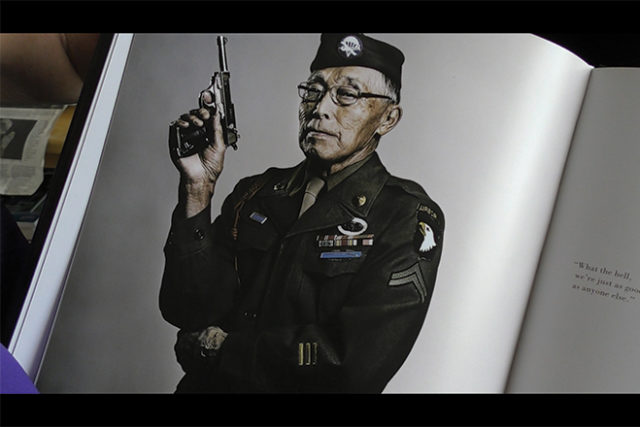

This caused much confusion in the internment camps, and great dissension arose even within families between the Issei, who immigrated and Nisei, who held American citizenship. Many young Nisei, wanting to change the circumstances they were placed in and leave hope for future generations, voluntarily enlisted in the American military, contrary to their family’s opposition. It is said that over 300 Nisei from just Minidoka alone applied to enlist. Only young Nisei were organized and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, whose members would later go on to be hailed as great heroes, was sent to the European battlefield.

5. Seattle’s Japantown After the War

Along with the end of the war came the end of life in internment camps for the Nikkei, but it took considerable hardships for them to return to their original lives. For those who had to relinquish their land and belongings prior to being sent to the camp, it was impossible to find jobs, much less a home due to racism against Nikkei.

Before the war, the area from what we now know as Pioneer Square to the Central District used to be a thriving neighborhood known as Japantown. However, because of newly migrated people, it was altered completely into a district occupied with various nationalities. Until Nikkei were able to find jobs and housing, they lived with a reliance on hotels, Japanese language schools, assembly halls and Buddhist temples that had long been under Japanese management.

It is said that the Japanese Culture Community Center of Washington, known as the Hunt Hotel at the time, offered Nikkei a place to stay, but took 14 years until all the residents could find jobs and homes and for the hotel to close down. If you walk around the modern-day international district, perhaps you can still feel the connection to the history experienced by the Nikkei immigrants, even today.

Nikkei Family History 4

Hiroshima and Seattle, Memories of War that Spanned an Ocean, interviewing Akiko Fujii about Fujii Family History

As the American economy stagnated, and criticism toward Nikkei immigrants grew stronger, there was a rise in families and even individual children wishing to return to Japan. Nikkei who briefly returned to Japan during the war were referred to as “Kibei Nisei.”

Minoru Fujii was one of those children. His wife, Aiko Fujii, is an affiliate of organizations such as the Seattle branch of the American calligraphy workshop and Betsuin Buddhist Temple, as well as a contributor to the Japanese community by way of calligraphy, flower arrangement, and tea ceremonies. His grandfather was Chojiro Fujii, a man who found success as an Issei immigrant through dairy farming and hotel management and set the foundation for Seattle’s Nikkei community by founding the Seattle Betsuin Buddhist Temple. After traveling to Japan, Minoru experienced the tragedy surrounding the atomic bomb in Hiroshima.

In 1935, as a young elementary school student, Minoru parted with his mother, Shige, and together with his brother, Hisashi, left their hometown of Seattle. They crossed the Pacific to live with Chojiro, who had returned to Hiroshima several years earlier. Estranging from their parents at such a tender age and then having lived together naturally made them very close siblings. Sometime later, Minoru enrolled in Kyushu University. During the war, he lived apart from his family with his parents in a Nikkei internment camp and his brother still living in Hiroshima.

In 1945, Minoru lost his brother in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Although Hisashi had planned on going to Hiroshima High School, the school he long desired to attend, due to the mobilization of middle school labor forces being extended by the war, he had just started school on August 1st, as opposed to the usual start date of April 1st. Minoru later relied on the commemorative publication marking the 70th anniversary of Hiroshima High School to convey how he felt on that day. “When the thought emerged that Hiroshima was really annihilated and that Hisashi is dead, my tears flowed endlessly, and I was stricken with heartrending sorrow,”

Meanwhile, during the war, Aiko and her family were evacuated to Fukuyama city and separated from their father, Katsurou, who was working for the Hiroshima City government as a school inspector on the Hiroshima City board of education. On the eve of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, August 5th, 1945, Fukuyama City was hit by an air raid of B-29 bombers. Nevertheless, Aiko and her family, who had departed from Hiroshima City, managed to escaped disaster.

The atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th at 8:15 am. Katsurou, who had remained in Hiroshima City, was working the graveyard shift the previous night. That morning he was fortunately in his home, of which was located a little bit outside the center of town. “His house was close to the foot of Mt. Hiji, under the shadow of the mountain. So, the incident passed, and his house took little to no damage. When it all happened, he wasn’t on the veranda but rather in the back room reading the newspaper. This saved his life because he wasn’t directly exposed to the radiation. The blast was so strong that it blew an iron sewing machine right off the veranda. He was incredibly lucky.” Aiko remarks.

Katsurou, with work-related responsibilities, immediately made his way to city hall near the Genbaku Dome. However, the bridge to city hall had collapsed and the river was filled with the bodies of bomb victims who had jumped into the water after being burned. It was a sight beyond imagination. Katsurou was also stricken with visible illnesses due to high levels of radiation, such as a throbbing in his head.

Aiko and her family did not know of their father’s safety until one week after the bomb dropped. Katsurou, who was identifying victims, met a villager of Hiroshima looking for his relatives. He delivered Katsurou’s business card to his family’s home in Fukuyama City, where Katsurou’s family was relieved to see his signature on the back of the card.

A month after the war ended, Aiko’s family returned to their home in Hiroshima City. Though despite the war coming to a close, confusion and famine persisted. “My father took the supply of rice we had received during our absence and let the children eat it, without taking a single grain for himself.” Aiko tearfully reflects. He let seven children eat the food rations he received and he himself subsisted only on vegetables he harvested from his garden such as cabbage, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, and cucumbers. Every night, as an evening drink, he also enjoyed one Tokkuri flask of Japanese sake. Although Hiroshima was ripe with radiation, he did not suffer any aftereffects. As Aiko later discovered, this was caused by the lack of irradiated foods in his diet and his frequent consumption of alcohol and vitamins in vegetables, both said to be effective in reducing the effects of radiation.

After the war, Minoru returned to Seattle and worked, later traveling to Hiroshima to find a spouse, where he met his now-wife Aiko through an arranged marriage. 10 years after the war, in 1955, Aiko’s name was officially entered into the family registry and she began her life in Seattle.

Aiko migrated to America, the once hostile country who dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Just what was on Aiko’s mind when she decided to live life in Seattle? “Because I was young at the time, I wasn’t happy or sad. My engagement was entirely left to my parents, so I did not have a sense of what was happening to me. But now I understand how my parents felt when they sent me off.”

Read Sharon Ideguchi’s related article;

https://napost.com/the-pulling-strength-from-the-past-to-build-a-better-future-fujii-family-history/

Editorial Note by Minami Hasegawa, North American Post Intern ~ Interviews spanning across half a year

Learning about the 150-year path that Nikkei immigrants followed was a completely new experience for me. Hearing stories from the people who actually experienced it was an interesting part of my study abroad. Just how much fear and hardship have Issei and their descendants been through? Whenever I imagined this, I had come to feel a strong connection between the Nikkei community, Seattle and the part of myself that I haven’t even thought about until now. The 150-year history since the beginning of Nikkei immigration is very dense and I hope that the many family histories and stories continue to be passed down.