By David Yamaguchi

The North American Post

ENGLISH READERS of this paper know much about the experiences of Japanese-American families during World War II. Many can also trace the wartime journey of the famed JA 442nd infantry across Europe. Yet, our knowledge base drops quickly when we pull back the viewpoint to include the settings in which Nisei linguists served in the Pacific, translating captured documents and questioning Japanese prisoners of war.

There are several reasons for this. The translators were widely dispersed among many units. There was lingering wartime and postwar secrecy, intended in part to protect the Japan-based relatives of those who served. There is simply a lesser volume of writing on the Pacific War than on the “first front” in Europe.

And there is one more thing. The context was savage, for the Japanese soldiers, unlike the Germans, would not surrender.

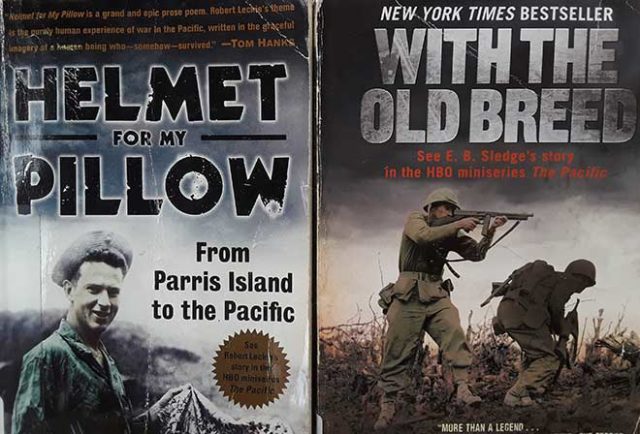

To begin to fill this gap in my own understanding, I recently read “Helmet for My Pillow” [Robert Lecke, 1957, 305 pp.] and “With the Old Breed” [E.B. Sledge, 1981, 326 pp.]. The two are the most famous first-person American accounts of the Pacific War. Both were used to write the story for the ten-part HBO miniseries, “The Pacific” (2010). Indeed, many video scenes come straight from the memoirs.

Written from the perspectives of ordinary marines, the two books together follow the island-hopping campaign of American marine and army infantry from Guadalcanal—in the Solomon Islands near Australia (Lecke, Aug-Dec. 1942)—through Peleliu—a now-forgotten island near the Philippines (Sledge, Sept-Oct. 1944)—to Okinawa (Lecke and Sledge, Apr-June 1945).

HELMET has remained in print and widely available for six decades. Reading only a few pages reveals why: its word craft is superb. Moreover, the author’s concise descriptions of his outer journey (what, when, where) are accompanied by a parallel inner soliloquy reminiscent of “Moby Dick.”

A hilarious outer scene example is where Lecke describes the marines’ elation on finding the withdrawing Japanese army’s supply of sake and beer on Guadalcanal before firing a shot.

“Case upon case… was found in a log-and-thatch warehouse not far west of our beach positions… Soon the dirt road paralleling the shoreline became an Oriental thoroughfare, thronged with dusty, grinning marines pushing rickshaws piled high with balloon-like half-gallon bottles of sake and cases of beer….

“We sat squatting. Because the huge sake bottles were difficult to pour, we had to push them to one another, and we drank by turns, as the Indians smoke the peace pipe. But our method needed the skills of a contortionist. One would grasp the huge bottle between one’s thighs, and then, with one’s head bent forward so that one’s mouth embraced the bottleneck, one would roll backward, allowing the cool white wine to pour down the throat.

“Oh, it was good…”

An inner-journey passage conveys Lecke’s fear of the inky night in a foxhole on Guadalcanal.

“It was a darkness without time…. I could not see but I dared not close my eyes….

“I could hear the enemy everywhere about me, whispering to each other and calling my name… Everything and all the world became my enemy, and soon my very body betrayed me and became my foe. My leg became a creeping Japanese, and then the other leg. My arms, too, and then my head.

“My heart was alone. It was me. I was my heart….

“It lay quivering, I lay quivering, in that rotten hole while the darkness gathered and all creation conspired for my heart.

“I know now why men light fires.”

OLD BREED, by contrast, has a rather recent publication date for a WWII memoir. It reflects the book’s long gestation, as the author first completed a 30-year career as a biology professor before finishing it from his field notes hidden in a bible. His memoir is the better of the two, for it reflects Sledge’s lengthier postwar education and life experience.

The main value of “Old Breed” for me is how it offers the clearest explanation I have read to date on the US rationale for dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The battles were ferocious, especially late in the war, when Japanese commanders had abandoned wasteful banzai attacks for interlocking defensive positions in bunkers and former mines.

Some 128,000 Japanese soldiers, 42,000 Okinawa civilians, and 7,700 US marines died on Okinawa, the “last battle” before the slated invasion of the Japanese mainland.

Moreover, the fighting was commonly hand-to-hand—akin to that of medieval Europe—as Japanese soldiers armed with swords leaped into the foxholes of marines at night. Accordingly, the latter had to place knives and shovels where they could grab them before sleeping.

For JA readers, the somberness of both books departs when, here and there, it becomes obvious that the US troops have JA interpreters with them, helping them end the war, and saving many Japanese lives. A supplementary Google search on “Nisei linguists” reveals that Guadalcanal was the proving ground where they demonstrated their value.

Bottom line, both “Helmet” and “Old Breed” are worth reading. I recommend them together for the perspective they provide on US-Japan history, on JA history, and on the human condition. You’ll finish both in a week.