By David Yamaguchi

The North American Post

Sometimes, when interviewing someone for this column, it becomes obvious that there is someone else in the room that is just as interesting as the person I went to interview. In those cases, I make a mental note that I must follow up with the second person at a later date.

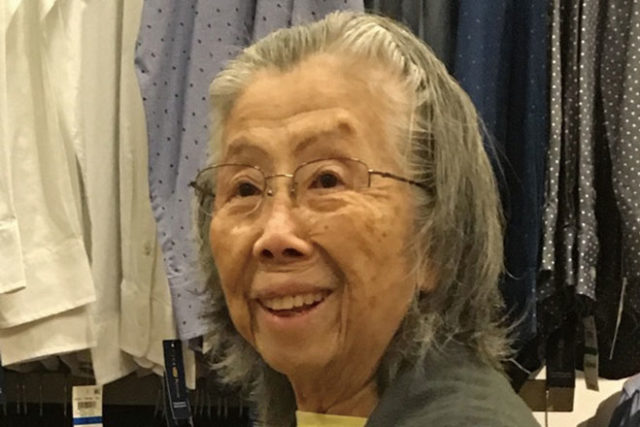

That was my experience when interviewing Kenichi “Ken” Sato for the 2016 Father’s Day issue. For near him sat his wife, Sarah, who turned 92 in 2017.

On meeting Mrs. Sato, two things strike the visitor. One is that she is outspoken, not a quiet listener like many Seattle Nisei women who are her age-peers.

“We were the majority in Hawaii,” she explains. On a later visit, she would show me her McKinley High School, Honolulu, album.

Besides her outspokenness, a second impression that strikes the visitor is that Mrs. Sato—“Call me Sarah,” she says—is a master knitter and sewer. She always has some amazing craft project on her lap. It is natural to wonder how and where she acquired these skills.

There was a lady who taught her and others at the Tule Lake internment camp, she answers simply.

A daughter chimes in:

“It was like Ken Mochizuki’s book, ‘Baseball Saved Us.’ For young women, instead of sports, however, it was crafts.”

This is stunning to a visitor. For as I would learn across later visits, Sarah’s life story lies far outside the typical Japanese-American narrative. It is a potboiler of a story, the stuff of eleven-part Japanese TV dramas. It is a monogatari.

“Aren’t you a Sansei from Hawaii?” I asked. (Immigration to Hawaii from Japan occurred a generation before that to the US mainland.) What were you doing at Tule Lake? What did your father do for a living? Did he do a lot of Japanese-community volunteer work (which would make him an influential “community leader” in the eyes of the FBI)?

“No, he didn’t have time for that,” Sarah says, for her father had been a crew chief for a small group of Japanese stevedores at the docks. He supervised them loading and unloading ships 12-15 hours a day. Owing to his job, he didn’t have time for Japanese community volunteer work.

In addition to knowing the harbor and docks, her Kibei-Nisei father had one additional strike against him in the eyes of the U.S. government. When he had lived in Japan, he had been drafted and so had served in the Japanese army.

In the broader context of JA internment, it makes some sense that Sarah’s father was among those detained, at first in Hawaii at the Sand Island internment camp. Many Americans felt that Hawaii JAs must have been involved in espionage leading up to the Pearl Harbor attack. There was intense political pressure to “do something.” But why did this involve Sarah, his then 17 year-old daughter?

Well, her father had refused to sign the guardianship papers that would allow her to complete her last year at McKinley with her classmates by staying with an aunt. Her father had wanted to keep the family together. If he was on the list destined for mainland internment, they would all go together. If his wife and children were to stay behind, they would have a hard time making ends meet. There were four children to feed (Sarah was the eldest; the youngest was eleven.)

Sarah’s main point—which she feels she didn’t emphasize enough in her Densho interview—is that the experiences of interned Hawaii JAs differed markedly from those on the U.S. West Coast in one key respect. Here, everyone went to the camps. By contrast, in Hawaii, only 1200-1800 did.

The consequence was overnight prejudice within the JA island community. People stopped associating with those interned—some even with their own relatives—out of fear of being added to the list of those slated for internment.

Tears still well in Sarah’s eyes when she remembers those days. It really hurt. Overnight, she lost all her friends except for two classmates with whom she had been friends since junior high.

To be continued.