By Nick Turner

It was in the evening of the third day of the Minidoka Pilgrimage—an annual trip to the incarceration camp in Twin Falls, Idaho where Japanese-Americans were held during World War II—that I spoke with Irene Saito. The others were eating and drinking and singing karaoke just down the hallway. The two of us had found a quiet place at a table in the cafeteria, but music and laughter continued to stumble in through the cracked door. We sat down and I took my pen from behind my ear. I pressed a button on my voice recorder and slid it across the table.

“I came here for a very specific reason,” she told me. “My father was taken by the FBI the day Pearl Harbor was bombed. I don’t know what happened to him except that he was found not guilty so he was sent to Minidoka where the rest of my family was.”

“The problem is, I’m having a real difficult time getting records because they spelled his name four different ways,” she said with a chuckle.

Irene’s father, Teiji, was a first-generation immigrant who came to the United States when he was 15 years old. He was “bound and determined” not to go back to Japan, Irene said. He worked in a cannery, did all kinds of odd jobs and eventually ended up working in a hotel as a bellman.

Military officials stayed in the same hotel, Irene explained. On the same day as the attack on Pearl Harbor, Teiji was detained and sent to a detention center in Monday, according to records.

“Maybe they suspected he was spying on them,” Irene said. But Teiji was found not guilty of espionage and was promptly sent to the Minidoka Incarceration Camp, where he joined the rest of his family.

Irene wanted to know what happened to her father during the time he was arrested and when he was sent to Minidoka. She applied for records in the national archives and to the Department of Justice, but both said no such documents existed. Irene knew that wasn’t true.

“That was one motivation for me to come here, to find more information about what happened to my dad,” she said. “That was a real big missing piece in my life, and I wanted to close that loop.”

The other motivation, she said, was her mother. Irene was born in 1943. Her mother, Kimi Saito, died of a ruptured appendix in 1944.

“I only had one year with her,” Irene said. “I really didn’t have an opportunity to get to know her or know much about her, and so I’ve been on this long quest to

figure out who my mother really was and what she was like.”

Kimi gave birth to Irene while the family was incarcerated in Minidoka. In the midst of all that was happening, she shouldered the burden of raising a child in a place with no running water, electricity or any of the amenities that most parents would demand. She also took care of Irene’s uncle whose mother was too busy taking care of her husband who had just suffered a stroke.

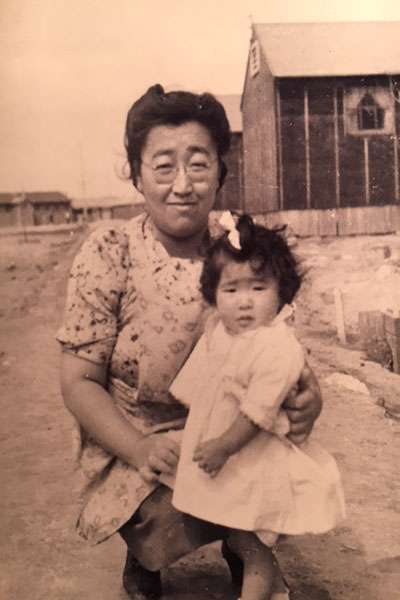

Irene tried everything to find out more about her mother. She tracked down people who knew Kimi, like the daughter of a Buddhist minister whose mother knew her, or the woman who played at Kimi and Teiji’s wedding. None of them gave Irene the answers she was looking for. The only recollection she had of her mother was a photograph taken by a reporter. In search of more, Irene came on her first Minidoka Pilgrimage in 2015.

“When I came here, I didn’t know what to expect. I had to come to see if I could somehow connect with my mother and be where she was the last three years of her life,” she said. “It was a very emotional journey.”

Irene came again this year on the Pilgrimage, but this year she brought along her nephew and husband.

“It was such a powerful experience for me to be on this pilgrimage. What I found, again, is this overwhelming sense of community, of being on sacred ground, that there was blood, sweat and tears that were shed on this ground, and that I had to respect and honor it.

“I wanted to come back and bring my husband and my nephew,” she added.” I want to make sure the stories of our family never get lost.”