By David Yamaguchi

The North American Post

By now, readers of this column may recognize two common patterns for multi-part series here. One is that there is simply far more to a topic than I can cover in one essay. I get too engrossed. The second is that I sometimes fail to get a first story right under deadline, necessitating a correction. Today’s follow-up reflects both trends.

To begin, see if you can spot the error in the following, which slipped through to my printed column of Dec. 15, explaining the moon’s hollow appearance in the “Iga no Tsubone” woodblock at right:

“… the Meiji [1868-1912] version is the first to include what appears to be an eclipse. In fact, the image is [a] near-perfect drawing of a “total lunar eclipse,” an eclipse where the moon’s face darkens in Earth’s shadow. This happens when the moon is too far from Earth to fully obscure the sun.”

Here, it is helpful to review the difference between a solar eclipse and a lunar eclipse. For the former, the sequence of alignment of planets and the moon is Sun-Moon-Earth; for the latter, it is Sun-Earth-Moon.

Thus, the last sentence of my earlier paragraph should have read, “This happens when the moon falls entirely in Earth’s shadow.” The face of the moon remains weakly lit owing to light that is refracted—bent—around Earth. Moreover, the edges of the moon can be illuminated brightly—by direct sunlight—just before or after total eclipse.

On Dec. 15, I also made a historical error besides the writing one. While I guessed—correctly—that eclipses must have been in the news at the time the woodblock was made, I attributed it to the impending total solar eclipse of August 1886 over the Atlantic Ocean.

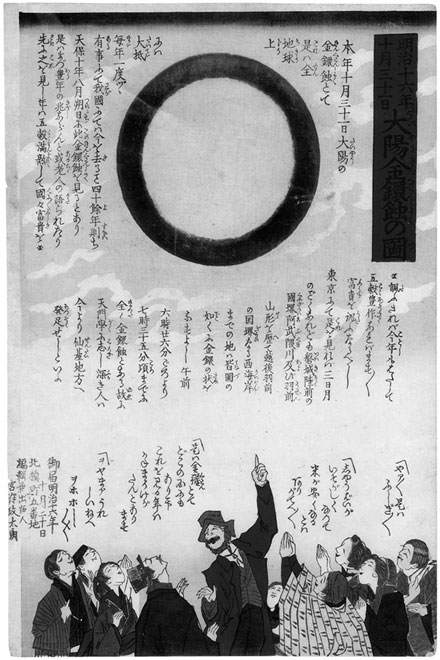

After further reading, it seems more likely that artist Taiso was influenced by news and woodblock coverage of a slightly earlier solar eclipse in Japan, that of October 31, 1883. Notably, this event was an annular eclipse, in which the sun becomes a golden ring around a jet-black moon.

Unfortunately, the woodblock of the 1883 eclipse, apparently made in advance of the event, has the colors of the eclipse reversed. The National Astronomical Observatory of Japan website attributes this to a lack of reference books in Japan at the time.

In addition to illustrating the evolution of Japanese understanding of eclipses, the Meiji-era woodblocks are intriguing because they illustrate two concepts relevant to Nikkei readers today. One is how the woodblocks capture the beginnings of exchanges of people and ideas between Japan and the West. The second is the persistence of the old technology of woodblock printing in parallel with photography through the period. It is not that Japan lacked cameras and film. It was that winning images could be transmitted to the masses more cheaply by woodblock through special editions of newspapers.

In early 2017, we will review additional Meiji solar eclipses as time and space allow.