By David Yamaguchi

The North American Post

Readers of this column may remember that during the holidays, I like to tell a tall story from the past, in the way that I remember family elders doing around the dining room table at my grandparents’ house. This one concerns a summer fishing adventure I had with Dad, probably the summer after I finished high school.

One day, Dad came home from work and asked if I wanted to join him on a salmon fishing trip to Westport or Ilwaco, I don’t now remember. I can fix the time because my brother Gary didn’t come, so he must have been away working. For if that lives-to-fish nut was around, he would have come too, as certainly as rain falls in Seattle.

In any case, this would not be a typical sports-fishing trip. For through the course of conversations that Dad routinely held with other businessmen in the course of running our family store, he had met a man who was a commercial salmon fisherman on the side. The man had invited Dad and me to join him on a trip to sea in his boat. The deal was that we would each work as deckhands, helping with the fishing. In return, we’d get a fishing trip, learn about commercial fishing, and take home a few fish each.

ON ARRIVAL AT THE DOCK, it turned out that the adjoining boat was also shorthanded and wanted me to help them. In retrospect, I can see how the new proposal made sense, because it is easier to make effective use of one greenhorn volunteer than two. And so the revised agreement was made that I would get on that boat and Dad would get on his friend’s, and that we’d meet up at the dock later. And so I shipped out with a father with a boy about my age. I would be the boy’s helper.

From the boy—who had done the work before—I learned the basics of how commercial fishing works, or at least did in those days. We started by lowering the end of a long, weighted, wrapped-steel cable into the sea. There were two such cables, which dangled from metal booms on the sides of the boat.

Next, about every ten feet, we clipped on an elaborate wire leader set-up. It consisted of a large, shiny-metal “flasher,” a plastic lure, and of course, a hook.

Near the upper end of each cable we attached a white buoy. When the skipper idled the engine, the movement of these floats would tell us what was happening below, like a bobber in sports fishing.

The skipper-father had emphasized to us boys running out the cables and leaders the cost of each leader set-up, which I recall as $20 apiece. At 100 leaders per cable x 2, we had $4000+ dangling from the boat. As he was trying to make a profit, we were instructed to try to not lose the leaders, for example, by failing to close their attaching clips properly.

I helped the son get the two cables out while his father ran the boat, and before long, we were fishing. After the cables had been out a while, I saw that their white buoys were no longer stationary alongside the boat. They were being dragged around by fish!

At that point, the son would flip one of the electric winches with which we had lowered the cables. Then the cable would come up, along with huge King salmon interspersed with smaller silver salmon. The fish had no say in the matter. Their fighting was no match for the power of the winch. As they say, it was like shooting fish in a barrel.

Well, all this was going swell. It was a nice summer day. We boys were catching fish. The skipper was happy. Until it all went to pot.

FOR THE SKIPPER had started drinking in his wheelhouse. And then the son, in hurriedly lowering one cable down after we had emptied it of fish, made a mistake. He lowered the cable too far, and its end slipped off the winch into the water.

Right away, we boys knew we were in trouble. For in under a minute, we had nearly lost over $2000 worth of gear. The skipper came boiling out of the wheelhouse in a rage. I had never seen a mad drunk before. It was not a pretty scene.

I say “nearly” above, because the lost cable was still dangling from its white buoy, which was adrift on the wide blue sea. This was probably the main purpose of the buoy: it was a safeguard against that very mistake.

Well, the skipper pulled up alongside the buoy, which by then was again being pulled around by fish, and the boy brought the loose upper end of its cable aboard with a gaffe hook. But in his nervousness in re-attaching the cable to the winch, with his angry father screaming over him, the boy had slipped with the pliers, and it went overboard!

Today, as an adult, I know that every critical piece of field equipment needs to have one backup—if not two. The problem was that this father and son had only one pair of pliers on board, which was essential for re-attaching the cable to the winch.

So at this point, we really had lost the $2000, plus all the fish on the drifting cable. While other boats were around—we could hear their chatter on the short-wave radio—the boats fished apart. This was in part out of necessity, to keep their cables from tangling. No doubt there was also friendly competition involved; after all, this was fishing. So for all practical, non-life-threatening purposes, we were alone on the sea.

Eventually, we decided that we at least needed to bring the other still-attached cable in, to gets its fish, and in that way to minimize our losses.

And so the boy and I began bringing that cable in, knocking its fish into the hold hatch as we went.

AND THEN WE SAW what remains the most unbelievable sight I have ever seen. It was the pliers, dangling from one of the hooks.

For in twirling its way down through the depths of the ocean, the pliers had intercepted one of the leaders—just right—and snagged! We swung it on board.

The skipper, who saw it happen from his wheelhouse, came out. He looked at the pliers, the partially brought-in cable, and the two grinning boys. He was stunned, silent, thinking.

And then he said, “Well, I can’t beat that!” And he went back into his wheelhouse.

The boy and I brought in both cables, all the fish, and the skipper steered us back to the dock. We cleaned up the boat, the skipper gave me my fish, and I went off to find Dad at his boat.

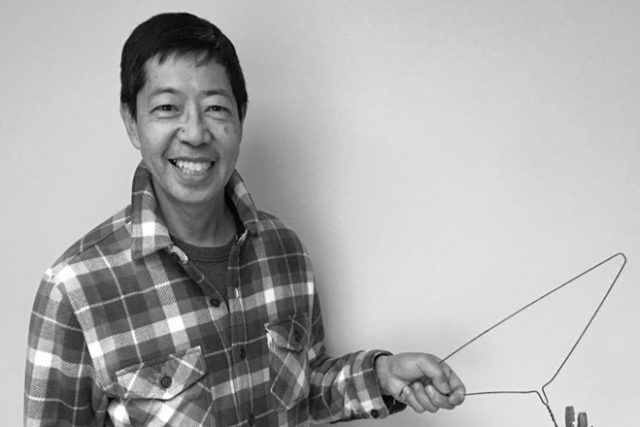

AS I WAS WRITING THIS, I had to get out a pair of ordinary pliers, similar to the one we caught in the ocean 41 years ago. I next found a wire clothes hanger. This is a reasonable facsimile for the large commercial fishing hook that must have been at the end of the wire leader. Then I hung the pliers on the hook the only way it would: by the “X” between the crossing handles with the handles dangling. It is a reasonable experiment that had not occurred to me to try until now.

When one does so, the pliers balance remarkably well! You can prove this to yourself, at home.

Next, try jiggling the hook around, as the hook of this story must have been jiggled by fish and by stop-and-start raising. While the pliers stay on—for the most part—it is also easy enough for them to become imbalanced and fall away.

It is possible that the wire fishing leader entangled the pliers, to help hold it in place. I no longer remember.

WHEN GARY AND I were younger, we used to devour the Sunday comics. In those days there was a series called “Ripley’s Believe It or Not,” which survives online today. It features some tall tale, where I recall the caption for the last panel sometimes read, “Believe it or not!”

And so I will end this fishing yarn by borrowing that timeless line:

“Believe it or not!”