By David Yamaguchi

The North American Post

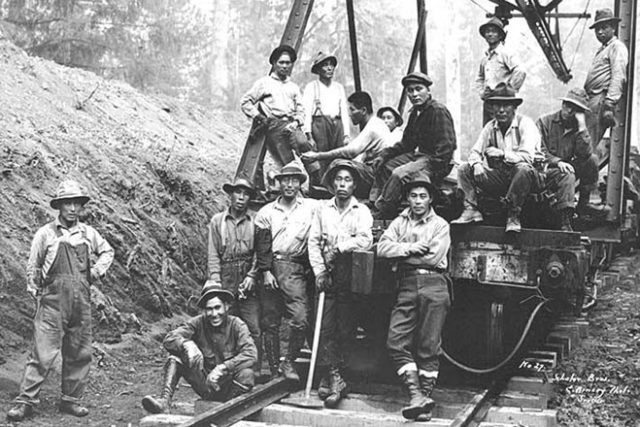

Last week, I submitted my article wistfully, for the photo I had found to accompany it shows only the living environment of Issei laborers in a Washington logging camp in the 1920s. It falls short of showing the nature of the work done by those pictured.

Moreover, as my deadline loomed, I was just learning the extent of surviving photos of Issei employees in southwest Washington lumbering. The images are in the University of Washington Digital Media collection.

The new-to-me photos were all taken by Clark Kinsey, the older brother of widely known Northwest logging photographer Darius Kinsey. As is evident here, the elder Kinsey’s compositions—the arrangement of his subjects in space—are similarly superb. Yet his work did not become as famous as his brother’s largely due to medium.

Clark used nitrocellulose film, which offered him the advantage of being able to develop and print images in the field. Its disadvantage is that these unstable negatives would decay over time, so four-fifths of the 50,000 images he took have been lost.

This outcome is unfortunate, for Clark Kinsey captured many “Asian workers” in action (including that of Walville workers I mistakenly earlier credited to Darius in the Sept. 22 issue). Probably few readers have seen Clark’s surviving images, as they have only recently been stabilized and entered into the digital archives.

While the subjects are described vaguely as “Asian workers,” even by the UW archivists, it seems to me that those pictured can only be Japanese. For the surviving photos date from about 1920-1940, four to eight decades after passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

There remains the remote possibility that some of the workers are Chinese, for 150,000 are believed to have migrated illegally after 1882 as “paper sons,” offspring ostensibly born of Chinese fathers living in the United States. This ruse was made possible by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and ensuing fire that destroyed official Chinese immigration records.

To me, however, it seems unlikely that such late-arriving Chinese could have made their way in numbers to rural Washington forests from Angel Island, their California point-of-entry. By contrast, arriving Japanese were met by labor contractors in Seattle.

The Japanese workers laid the tracks needed to get the logs out of the forest. They set the cables needed to pull the logs to the trains. In saw mills, they sorted lumber by dimension coming off the “green chain.” In at least one mill—Walville—they worked the night shift while Caucasian co-workers slept.

The image here is from a set of 36 in the UW archives that can be perused by searching online for “Kinsey Brothers photos of the Lumber Industry.” There, click on the subcategory “Asian workers.”