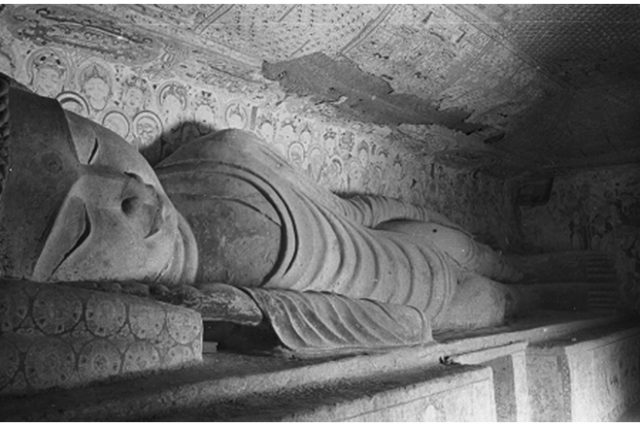

A reclining Buddha at Dunguang. Photo, James and Lucy Lo, 1943.

To understand life in Japanese villages, learning something of Buddhism—the ancient religion of Asia—is essential. Such thinking applies even to communities as far removed from the ancestral islands as those lining the shores of Lake Washington. Thus, the new Seattle Asian Art Museum photographic and documents exhibit, “Journey to Dunhuang: Buddhist Art of the Silk Road Caves” (March 5-June 12), would be worth seeing for all readers of this paper.

The broad strokes of Dunhuang are that a Buddhist monk named Yuezun, on visiting the desert oasis in AD 366, hit on the idea of carving caves in the cliffs for housing Buddhist statuary and murals. Across the next thousand years, local miners and artists built on that vision, ultimately creating a body of work so exquisite that Premier Chou Enlai would designate them a rare cultural site off limits to the Red Guards who would destroy much of the country’s antiquities during the Cultural Revolution.

The exhibit draws heavily on the black and white photography of photojournalist husband-and-wife team James and Lucy Lo, who in 1943 had the presence of mind to journey to the remote caves by horse and donkey-cart while the rest of the world had gone mad. Many of the scenes they captured are no longer visible owing to later cave modifications.

What is striking is the antiquity of the art, relative to that of Japan. For example, a useful cultural reference time-point for understanding Japanese history is August 4, AD 781, which is when the first precise date of eruption of Mount Fuji enters the written record. By contrast, my notes from the Dunhuang exhibit in part read, “Cave 254, Northern Wei dynasty (AD 439-534); Cave 397, Sui to Early Tang (581-704)…”

Also new to me were bilingual fragments of Buddhist documents associated with the caves, where perhaps 80% of the content is written in Old Uyghur (old Turkic), which resembles English cursive writing, interspersed with Chinese. The languages swirling about the site, at the confluence of the Taklaman and Gobi deserts, were Chinese, Tibetan, Uyghur, Tingut, and Hebrew.

Leaving the exhibit still perplexed on the significance of the Dunhuang cave art to Nikkei, I sought out an old wall map of Buddhism’s spread across Asia, which I was pleased to find still on display elsewhere in the museum. And there, both Dunhuang’s Japan connection and its relevance to our present-day world “clicked” into place. To reach Japan via Korea, Buddhism first had to reach Beijing. If China were a clock, that northern capital city lies at two o’clock. By contrast, Buddhism’s origin in northeast India is at 7 o’clock.

Yet a simple traverse across the clock-face was impossible, for that route is blocked by the Himalayas. Thus, Buddhism reached Japan by traversing long arcs around the clock rim. The clockwise northern route first leads northwest, through Pakistan. That path explains the presence of immense Buddhist statues in cliff faces at Bamiyan, central Afghanistan (9 o’clock), which captured world attention when they were dynamited in 2001 by the Taliban. In any case, the route east from Afghanistan to Beijing leads straight through Mogao, the most famous of the Dunhuang caves.

Continental armchair wandering aside, if the idea of spending an hour musing on miners carving 500 caves, and artists filling them with 2400 sculptures surrounded by murals strikes your fancy, then visit the SAAM exhibit before its cave-images and documents are packed up, and continue on their journey.

PS. The buzz in the exhibit room on its March 5 opening was on the associated “Saturday University” lecture, on present-day conservation of the caves, scheduled for April 9 at 9:30 – 11 a.m.