By David Yamaguchi,

OCTOBER 23, 2018 is the 150th anniversary of the start of Japan’s Meiji period, which dates from October 1868 to July 30, 1912. It is the imperial reign when Japan opened its doors to the West. It included the arrival of the first Japanese Americans, the Issei, on these shores.

Thus, it would be appropriate for this paper to include occasional retrospective articles on the Meiji era across the coming year. To set the stage for such pieces, let us begin today by examining two important early Meiji artworks that illustrate Japan’s understanding of written English at the time. English, then and now, has been one of the keys to effective international trade and diplomacy.

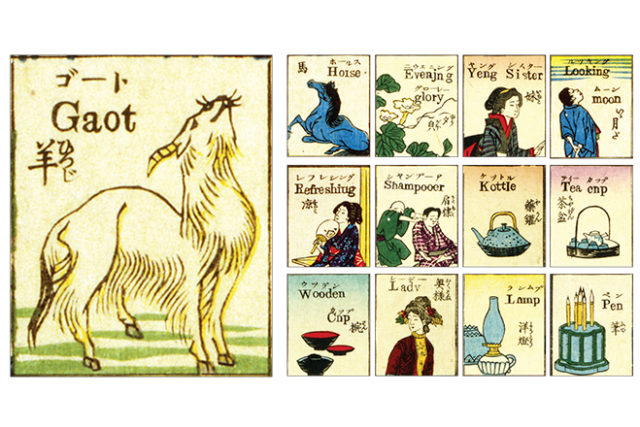

The pieces are Tsunajima Kamekichi’s Ryuukou Eigo Zukushi, which have been translated as “Fashionable Melange of English Words.” They consist of two woodblock prints, each comprised of a set of 42 cards depicting English words. Their corner notes date them to Meiji 20, April, or 1887.

In examining the individual cards, we can see that there were marvelous animals in the English-speaking world. Of these, my favorite is the Gaot.

You’ve never heard of a Gaot, you say.

To show that I didn’t make it up, I refer the reader to its picture, above.

It is near that of the Hoise.

Such strange animals were accompanied by unusual plants, people, and housewares. There is the Evenjng Glory, perhaps admired by a Yeng Sister. She pursued activities like Looking Moon, and Refreshiug, sometimes with a massage from a Shampooer. In the evenings, she drank tea steeped in a Kottle from a Tea Cnp. For soup, she used a Wooden Cnp.

Somehow, all these remarkable things and people have nearly vanished across the three generations that separate me from my grandpa’s lifetime.

Flippant Sansei musings aside, the power of Tsunajima’s work lies not in what he got wrong, emphasized here, but in what he got right. I picked only the most amusing cards from the set, most of the balance of which are spot on.

More important is the way Tsunajima’s drawings comprise a snapshot of where Japan was on its internationalization journey in Meiji 20. It is just like how these pages capture where we are, as a Nikkei community, in Heisei 30.

Tsunajima’s Eigo woodblocks, among the best known of his life’s work, have withstood the test of time. Today, prints of them reside in the US Library of Congress, alongside books from the original library of Thomas Jefferson. Outside of that esteemed national library, images of the Fashionable Melange are available for purchase online internationally, printed on t-shirts, coffee mugs, handbags, and the like.

The woodblock images have survived to the present probably because they do what mere words cannot. They capture the spirit of the Meiji era. It was a bold time of change when a small island country reached out to the world and tried—with charm and whimsy—to understand and communicate with it. In America, only six months before, a great statue had been dedicated of a Ladv holding a Lump.

Vestiges of these sentiments flow through these pages today, as we strive—with Pen and ink—to continue the bilingual journey begun so long ago.