By Nana Mizushima For The North American Post

Editor’s note. On May 13, we introduced cello-playing local writer Nana Mizushima, who translated the memoir, “Tei” by Tei Fujiwara. It describes the mother-of-three’s journey fleeing the Russian invasion of Manchuria in August 1945. As the story parallels that of many Ukrainian families today, we reprint its opening chapter below.

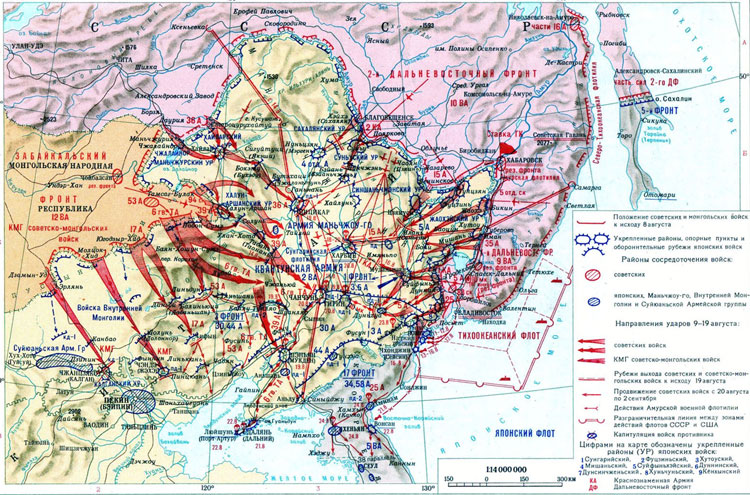

Tei Fujiwara, “Tei, A Memoir of the End of War and Beginning of Peace,” 2014, Tonnbo Books, 326 pp. Right: Chapter index map showing the locations of Shinkyo City (now Changchun, China) and Fusan (the port of departure, about 1250 km (775 miles) away. Photo: David Yamaguchi

Tei Fujiwara, “Tei, A Memoir of the End of War and Beginning of Peace,” 2014, Tonnbo Books, 326 pp. Right: Chapter index map showing the locations of Shinkyo City (now Changchun, China) and Fusan (the port of departure, about 1250 km (775 miles) away. Photo: David Yamaguchi

Shinkyo City, Manchuria August 9, 1945, around 10:30 p.m.

I heard a loud knocking at the front door. The children were asleep. My husband and I were talking about getting to bed soon because we had stayed up late the night before.

“Mr. Fujiwara! Mr. Fujiwara! We’re from the meteorological station!” a young man shouted from outside.

My husband and I opened the front door to find two young uniformed men holding rifles.

“Sir? Are you Mr. Fujiwara? Please come immediately to the office,” said one of them.

My husband asked, “What is going on?”

“Sir, we don’t know what the reason is but everyone is being called to an emergency meeting. Please cooperate and come right away!” The two rushed off to the next house to continue their mission.

When I closed the door, I felt light-headed. My intuition told me that I shouldn’t let my husband go into the pitch-dark night by himself. “Are you sure you want to go out alone?” I asked.

Right after I said that, I peered into my husband’s eyes to try to extract what vital knowledge he had. I was sure that there was something he didn’t tell me, something he hid about what was going on with the war. The last two or three days, uneasiness clouded his eyes.

“Don’t worry. I want you to wait for me,” he said. Then he sighed. “It looks like the day has finally come,” he added and he opened the door again. “Here. Listen… it definitely isn’t the same old Shinkyo City we know.”

I turned my attention to the night and listened carefully. In the distance, I heard cars running, people’s nervous voices, and other restless noises. A big change was about to happen. It was like an omen, vibrating all around us in the dark night air where the new moon shed no light. “Has the day finally arrived? Is this it?” I asked. I sat down in the dark, narrow hallway as all the strength drained from my body. I clung to the bottom of my husband’s jacket and trembled.

“Baka! You fool,” he scolded me. “What are you doing? Hurry; you’ve got to get everything ready so that we can leave this place right away.”

“Leave here? Leave our home — to go where?” I asked.

“I don’t know myself. I don’t even know yet if we’re really leaving or not — but we’ve got to prepare ourselves; we’ve got to be ready.”

He hurriedly wrapped his uniform leggings around his trousers and rushed out. The meteorological station where my husband worked was in the suburbs south of Shinkyo, in a place called Nanrei. From here, it was going to take at least thirty minutes for him to get there by foot. Even if he turned right around, it would be about an hour before he got back home.

I went upstairs and tried to decide what to do. From the second-floor window, I saw confirmation of my fears. Even though there was an official blackout order, scarlet points of light flickered between the window shades of the neighbors’ houses.

Tonight, it wasn’t just my home. Everywhere, in every home, terrible thoughts ran through people’s minds. Turmoil and fear spread, like a plague. The shadows in the windows moved about hastily, as if they were in a panic.

”I’ve got to do something,” I told myself and opened up our emergency suitcase.

Inside, our winter clothes — children’s and adults’ — were neatly packed. What about emergency food? Some packages — sugar, hard biscuits, and canned goods — were already packed inside. If we have to leave Shinkyo tonight and go who knows how far, other than these things, what in the world should we take? As I thought about this, my heart pounded faster and faster, and soon any semblance of rational thought fled my mind. I couldn’t think.

Under the mosquito netting hung in the center of the eight tatami-mat room, I saw the faces of my children, all sleeping together on one bed — limbs and bodies intertwined as if they were one creature. How could we possibly leave this house and get very far with these children? My two boys — Masahiro was five years old and Masahiko was only two. My baby girl, Sakiko, was a newborn who had just turned one month old. As I nervously packed and unpacked things in and out of the backpack and suitcase, I was overcome with dread, and my eyes welled up.

“I’m not strong enough for this. There was nothing I could do by myself,” I thought. A woman alone with her children. All I could do was wait for my husband to come back. As I sat quietly, various sounds outside seemed to press in on my home from far away. Looking out again from the window, I saw the unfamiliar sight of the headlights of many trucks reflecting off the white walls of our housing compound along the Daido Daigai Road.

My husband came home. His pale face was so tense that he seemed like a different man from the one who usually stood before me. “We’ve got to get to the Shinkyo Station by 1:30 this morning,” he said.

“What!” I cried. “Shinkyo Station?”

“We’ve got to evacuate by train,” he said.

“Why?” I asked.

He explained the situation quickly in terse sentences. The military families of the Kanto Army were already moving. The authorities had issued an order; families of the civil servants must do the same. There was the real possibility that Shinkyo City would be engulfed in the turmoil of this war. I thought, “Did that mean the Soviets were invading the city?” Any Japanese who remained would be risking his life. We had to leave right away. Other families besides those of the meteorological station were also preparing to leave. We needed to evacuate immediately.

He said, “We’ve been assigned to a train. In just thirty minutes… we’re supposed to leave. Hurry!” My husband instructed me as if he were ordering the troops.

“Of course, you’re coming too, aren’t you?” I asked. There wasn’t time to argue with him any more than this. I felt that as long as we were all together we would somehow survive. I looked at his face.

“I will take you as far as the train station but I’ve got to stay here,” he said.

“What! You’re leaving me?” I was shocked. With fear and anger rising in me — like a woman who had lost her mind — I hurled harsh words at him. As I screamed, I barely heard him say, “I still have work to do…” and something about “…as a man in my position, I can’t leave without first finishing what needs to be done…” But he was overwhelmed by my anguish and stopped talking. He looked into my eyes. As I noticed my silent husband gazing at me, I realized that there was nothing I could say to change his mind. I stopped.

He put his hand on my shoulder as I crumpled in tears.

“Now hurry. Think about the children,” he said.

With those words, I regained my composure. I‘m a mother… a mother who has to save her children by running away. I became resolute. There was no room for crying now.

Once more, from the beginning, I organized our belongings. But with three children, how much could I carry? With just the essential things — the children’s winter clothes— the bags were full. I put two-year-old Masahiko piggyback in a sling across my back while my husband tied Sakiko, papoose-style, on top of his backpack. In both hands, he carried the other bags. Masahiro was just old enough to walk, carrying his own small bag. That was how we decided to get to Shinkyo Station.

As we opened the door, the cold night air blasted our faces and took my breath away. We had the children wear as much as they could. Since I was also dressed with layers of winter clothes, the dry cold wind blowing in from the Manchurian plains felt just right. From the many vegetable plants I had in our yard, I picked a couple of tomatoes and put them in my bag. My husband kept saying, “Hurry, hurry,” while I thought about how I wanted to properly pay my farewell respects to the neighbors, Mrs. Maeda and Mrs. Sato. But tonight, the six houses in our compound were dark and empty. Where did they go? I said good-bye to them silently as we walked out toward the Daido Daigai Road. As I looked back once more at our home of two years, I saw only a dark square shadow, and it looked like a pile of dirt.

Shinkyo Station was four kilometers away, straight on the Daido Daigai Road. But before we had even walked one kilometer, I was exhausted. My poor body had given birth to Sakiko just a month earlier, and I was in no condition to carry a toddler like Masahiko. I tried to catch my breath around Daido Park, but was overcome by a sadness that I have never felt before in my life. In front of us passed a truck heavily loaded with the military families and their luggage. There were parents like us who were fleeing, holding onto the hands of their small children. How could it be that just two hours earlier, my family had been living here in such peace? My husband and I had often admired the vast Manchurian night sky. Why do we now look at that same starry sight with such fear? What could a woman with children do? We passed the thickets of the park and, almost horizontally in front of us, a large shooting star flew across the sky.

I felt as if an icy blade were plunged into my chest — hopelessness bled into my body. I said, “Let’s go home. If I am going to die anyway, I’d like to die at home.”

My husband said nothing and kept marching. He took out his pocket watch and tried to look at it in the light of the stars. I knew he wanted me to keep walking. There were still three kilometers to go. I thought if I kept walking like this I would collapse, a body already weak from loss of blood.

“Please. Please… let’s go home,” I pleaded one more time. But I knew that I was making an impossible request.

Nana Mizushima scribbles under the pen name, “Nanako Water” (nanakowater.com). There, the next 11 chapters of “Tei” are available online, where the 12 chapters together span the book’s first 61 pages. Reviews are available on goodreads.com and japantimes.co.jp.