How I Met My Japanese Relatives

By Pamela A. Okano

For The North American Post

▲My dad and his siblings in Japan when they were children (ca 1920s). From left: Yoneko (Niki), Minoru (Min), Masaru (Phil) and Ayako (Janet). Photo: Densho, Okano Family Collection

My father was born in America in 1913. When he was nine, his parents sent him and his younger sister to their hometown on the island of Innoshima, Hiroshima Prefecture, to go to school. Eventually, my grandparents would send their next two younger children (of five) there as well.

My father was born in America in 1913. When he was nine, his parents sent him and his younger sister to their hometown on the island of Innoshima, Hiroshima Prefecture, to go to school. Eventually, my grandparents would send their next two younger children (of five) there as well.

◀︎My almost great-aunt, the writer Hayashi Fumiko, and me in Onomichi, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan (2012).

Photo: Dick Birnbaum

The two younger ones came home earlier than planned, when the head of the household where they were staying died. But my dad and his sister stayed for 10 years. They attended school in nearby Onomichi, the closest town on the mainland of Hiroshima Prefecture.

Dad and his sister returned home in 1933. Japan had invaded Manchuria two years earlier. If they had stayed, Dad would undoubtedly have been drafted into the Japanese army.

My Okano grandparents moved back to Innoshima in 1955, at least in part, because they were so disgusted with how the US government had treated them during the war. In addition, they both had many relatives who still lived in the area.

Dad and his siblings continued to maintain some contact with their relatives back in Japan for many years. For example, when my uncle and dad would go mushroom hunting, they would send some of the matsutake to their Japanese relatives. And my aunties made periodic trips back to Innoshima to visit. But as the years passed, and my dad and most of his five siblings passed away, that contact more or less came to a halt.

In 2012, my partner and I decided to travel to Japan. I had gone to Japan once before, with my family, in the early 1980s. At that time, it was hard for Japanese people to understand why a person with a Japanese face and name couldn’t speak Japanese. Before our upcoming trip, I decided to learn a little Japanese so that I could at least explain why I couldn’t speak much Japanese. Accordingly, I enrolled in a small language school near my home for a few months of instruction.

We loved our trip to Japan. We decided to go again in 2014. By then, the language school had closed, so I enrolled in Japanese classes at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington (JCCCW).

▲ The Seto Inland Sea. Onomichi and Innoshima, the settings for this story, are on the right side of the map. Images: Google Maps

In the meantime, we decided that we should try to find my dad’s relatives during our Japan trip. Other Okano relatives in Seattle knew the family had last lived in the Habu area on Innoshima.

Innoshima, an island in the Seto Inland Sea, is primarily known as having been the base for the Murakami pirates, who long ago controlled navigation in the area. My aunt likes to joke that on Innoshima, residents’ last names are either Murakami or Okano. In fact, my grandmother’s maiden name was Okano, and she married an Innoshima Okano who was not a blood relative.

Innoshima, an island in the Seto Inland Sea, is primarily known as having been the base for the Murakami pirates, who long ago controlled navigation in the area. My aunt likes to joke that on Innoshima, residents’ last names are either Murakami or Okano. In fact, my grandmother’s maiden name was Okano, and she married an Innoshima Okano who was not a blood relative.

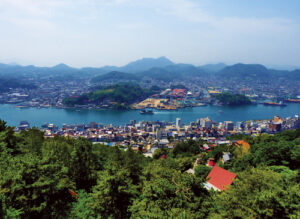

Innoshima is now part of Onomichi, a beautiful town on the mainland of Honshu, known as the gateway to Seto Inland Sea. The area has a Mediterranean feel. Lemons and flowers are grown there. Onomichi is also famous as a cinema center. Many Japanese movies—notably, Ozu’s “Tokyo Story” (1953)— have been partly filmed there. On weekends, the hotels are packed with bicyclists who go island-hopping by bridge or ferry across the Sea, 60 km (37 miles) to Imabari, Shikoku, on its southern shore.

Onomichi and Innoshima, showing the location of Habu. Images: Google Maps▲

When my cousins and I were children, our parents used to tell us that our grandma Okano’s brother once had a notorious affair with a famous Japanese author. We didn’t really believe this story. But when my partner and I arrived in Onomichi, we found a statue of the author, Hayashi Fumiko, who had lived there for part of her life. Research on the internet proved that the story was true — Hayashi was and is today a famous author, and our great uncle indeed had had a scandalous affair with her. The relationship ended when his family, most likely led by my grandmother, broke it up.

▲A view of the old part of Onomichi. Mukaishima Island and the mountains of Shikoku loom in the distance. Tamotsu and Hisako Hiraki with me at their home in Habu (2012).

We decided to take a bus to Innoshima to find my dad’s relatives. Would the bus stop in the Habu neighborhood? If so, what would we do once we got there? We had no idea what we would find, but I thought our best bet would be to go to the post office first.

The bus stopped in the Habu neighborhood, so we got off. Even though it was midday, no one was on the streets. If there was a post office, we never saw it. The first building we tried seemed to be vacant.

At the next building, we entered the first office that appeared to be occupied. It was a Japanese travel agency. No one spoke English.

◀︎The Hiraki family and me (2012). Photos: DB

◀︎The Hiraki family and me (2012). Photos: DB

I had been rehearsing what I was going to say in Japanese for months. I told them that as an American, I did not speak much Japanese. I explained that my father was born in the U.S. but went to school in Onomichi when he was a child, and that I thought his cousin was still living in Innoshima. The cousin’s name was “Hiraki Tamotsu” and my father’s name was “Okano Masaru.”

One of the women said, “Chotto matte kudasai” (please wait a moment).

She looked in a large book that appeared to be a directory. Then she said she would call dad’s cousin.

After the call ended, she said, “They live close to here. I will take you there.”

Once out of the building, we took a nearby road up a long steep hill. Soon we saw an elderly man walking toward us. It was my dad’s cousin coming to greet us. We thanked the lady from the travel agency and went with Hiraki-san to his house, where we met his wife, Hisako-san. Needless to say, they were very surprised to see us. I had thought it would take half a day to find my relatives. Instead, it took just 20 minutes!

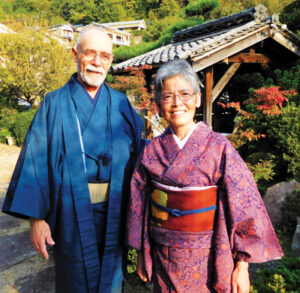

▲Dick and me dressed in kimonos on our second visit with my relatives (2014).

Photo: DB

We had loaded old family photos of the American branch of the Okanos onto a tablet. This turned out to have been a good idea, since a few months of Japanese class were insufficient for me to hold a real conversation with the Hirakis. They seemed to enjoy looking at the photos. Hisako- san even pulled out a box of photos and showed me one that was identical to the one that we were showing her.

▶︎From left: Tamotsu, Hisako and Uncle Bob in Onomichi (2016). Photo: Carol Okano

▶︎From left: Tamotsu, Hisako and Uncle Bob in Onomichi (2016). Photo: Carol Okano

I was able to tell them that my dad and all his siblings except the youngest, Uncle Bob, had passed away. They seemed happy to hear that Bob, the remaining Nisei family member closest in age to them, was still living. They fondly referred to him as “Bobby.”

In May 2016, the Hirakis’ son visited Seattle while he was on a business trip. Sadly, I missed him because I was in the hospital. But he had dinner with my partner and Uncle Bob and his wife Carol.

That summer, Uncle Bob, Aunt Carol, and their entire family all went to Innoshima to visit the Hirakis.

Hisako-san later told us, “They came on the hottest day of the year!”

It must have been over 100 degrees and very humid.

We again went to Innoshima the following November. By this time, the Hirakis’ son had moved his family from a neighboring town to a house next door to his elderly parents.

The combined Hiraki family entertained us in fine style. We enjoyed a sumptuous bento lunch at the local Hitachi facility. (Tamotsu had worked in Hitachi management.)

▲Uncle Bob and Aunt Carol with Hiraki family members at the cemetery, Habu (2016). Photo: CO

We told them that the American branch of the family was involved in many things Japanese. My cousin cofounded and still plays in a taiko group. My brother is the lead pounder at the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community’s annual mochitsuki. I dance at Bon Odori every year.

Hiraki-san’s granddaughter, Yuko, exclaimed, “They’re more Japanese than we are!” She also said, “My grandparents really enjoyed the (Bob Okano family) visit. They still talk about them.”

After lunch, they showed us some bomb shelters and told us that Innoshima had been bombed twice during the war. This was not surprising, since the island had been a shipbuilding site. But for me, it was a sobering thought — my country could have killed these nice people who were my own relatives.

Back at the Hiraki home, we found out that Tamotsu-san’s and Hisako san’s daughter-in-law had a hobby of collecting old kimono. She graciously volunteered to dress us both in kimono. Afterwards, the family treated us to tea and wagashi (traditional Japanese sweets).

Tamotsu Hiraki passed away in 2020 at the age of 93. My Uncle Bob passed away in 2021 at the age of 91. We are glad to have been able to meet Hiraki-san and also to have played a small part in enabling these two first cousins to meet one last time.

Reviewer’s (DY) notes. The Japan Inland Sea, the setting for Okano’s story, is also the landscape of many a Seattle-area JA family’s roots (“Inland Sea Roots,” napost.com, Jan. 2021). Family reunification stories like hers are still possible, because many JA families have rural origins. But the time window for doing so is dwindling…